1994

Pieter Hugo

12-02-2017 - 18-03-2017

Opening:

Rotterdam, front room

1994

comprises portraits of children born after 1994 in two countries, South Africa and Rwanda.

Major historical events took place in both these countries in 1994, and this series depicts a generation of children growing up in a post-revolutionary era, when the possibility of change was definite while its realisation remains uncertain.

Describing this body of work, Pieter Hugo says:

I happened to start the work in Rwanda, but I’ve been thinking about the year 1994 in relation to both countries over a period of 10 or 20 years. I noticed how the kids, particularly in South Africa, don’t carry the same historical baggage as their parents. I find their engagement with the world to be very refreshing in that they are not burdened by the past, but at the same time you witness them growing up with these liberation narratives that are in some ways fabrications. It’s like you know something they don’t know about the potential failure or shortcomings of these narratives …

Most of the images were taken in villages around Rwanda and South Africa. There’s a thin line between nature being seen as idyllic and as a place where terrible things happen – permeated by genocide, a constantly contested space. Seen as a metaphor, it’s as if the further you leave the city and its systems of control, the more primal things become. At times the children appear conservative, existing in an orderly world; at other times there’s something feral about them, as in Lord of the Flies, a place devoid of rules. This is most noticeable in the Rwanda images where clothes donated from Europe, with particular cultural significations, are transposed into a completely different context.

Being a parent myself has shifted my way of looking at kids dramatically, so there is the challenge of photographing children unsentimentally. The act of photographing a child is so different – and in many ways more difficult – to making a portrait of an adult. The normal power dynamics between photographer and subject are subtly shifted. I searched for children who seemed already to have fully formed personalities. There is an honesty and a forthrightness which cannot otherwise be evoked.

For Hugo, 1994 is a tableau that raises questions around history and post-conflict narratives as well as the portrayal of children in fractured and transitional times. He resists drawing conclusions, stating in a recent interview with Richard McClure: ‘There are always opposites present.’

'1994:' Pieter Hugo at the Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town

on 23 August 2016.

A lithe figure reclines in a gold, sequined cocktail dress that reaches to her knees. But for her dress, the girl is androgynous. She is positioned like Manet’s Olympia on a bank of loam. The wet ground around her is the same brown as her skin. I am mesmerised by the roots, worming their way through the soil beneath her form. She meets your gaze with a fashionista’s rueful scowl while creepers, with tendrils and heartshaped-leaves, infiltrate the frame.

AA Newsletter Aug23 Kuijers 1

Pieter Hugo, detail of Portrait 19, South Africa, 2016. C-print. © Pieter Hugo. All images courtesy of Stevenson Cape Town and Johannesburg.

This is Portrait #7, Rwanda, 2014, one of Pieter Hugo’s thirty-three life-size portraits of “born-frees” from Rwanda and South Africa. The enormity, elevation and clarity of the photographs are overwhelming and from each gazes one or more solemn children. They are posed in nature, strikingly at odds with the yokels and strangelings of Hugo’s previous exhibition ‘Messina/Musina’ or ‘Boerseun: Portraits of young Afrikaans farm boys.’ To situate these works in Hugo’s oeuvre is to realize that he has strayed into an uncharacteristically beautiful aesthetic.

Much of his previous work documents the idiosyncrasies at the fringes of humanity. His subjects appeared to be outsiders; too familiar to entirely reject but also uncomfortably awkward and pathetic. In stark contrast, the children in ‘1994’ don’t elicit sympathy – they are a host of impervious cherubim in clothes scrounged from adult humans. In these works Hugo’s attitude towards them seems envious and aspirational. For him, they represent the relief of finally shedding the deplorable, itchy skin of the past.

In 1994, the Apartheid government relinquished power to the African National Congress. In the same year an estimated eighthundred thousand people were killed in Rwanda in a genocide that is unparalleled in the post-Holocaust world. Although the two territories endured vastly different struggles they are analogous in many ways and both represent an attempt to rebuild and resurrect.

AA Newsletter Aug23 Kuijers 2

Pieter Hugo, detail of Portrait 7, Rwanda, 2014. C-print. © Pieter Hugo.

A South African native, Hugo has worked in Rwanda before, photographing victims and perpetrators of the genocide. He shot a sensitive and astutely-captioned series that showed how life continues but hurt lingers on; never forgotten, not quite forgiven, and eerie, but for the warm African sun and the jubilant Kitenge designs.

‘1994’ is less overt. It is a political exhibition by virtue of what is not there. His subjects do not know the scorched earth and the blood baths. They do not hold the cold metal of guns. Their range of understanding of violence and injustice is less than that of their parents. Hence, healing is one optimistic take-away from this exhibition. It appears that in their moments of relaxation these wise-eyed juveniles require no patronising parental supervision. However, it would be negligent not to ask to what degree Hugo’s subjects are still too vulnerable and larval to be counted as having a political bent.

Photographing children raises ethical questions because of the power asymmetry between photographer and subject. Children must assent to being photographed and the consent of a legal guardian must be acquired. Even then however, consent is often bought or acquired through an imbalance of power; creating a disparity between actual consent – the right toward self-determination – and a ‘consent’ that comes off the back of a ‘I owe you.’ Much of Hugo’s process is obscured from the gallery viewer so it is difficult to tell if his process took these factors into consideration. In a pre-emptive response to issues of exploitation and the inevitable question of identity politics, my opinion is that it is better to have the photograph – one that contains some truth, however adulterated it is by the gaze of the photographer – than to have none.

AA Newsletter Aug23 Kuijers 3

Pieter Hugo, detail of Portrait 16, South Africa, 2016, C-print. © Pieter Hugo

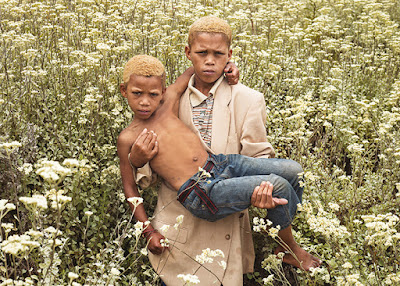

I do not believe that Hugo’s intention in this instance was to represent a political truth. ‘1994’ seems far more like the creation of an agrarian idyll than photo-journalism. For this reason, his subjects straddle the line between evidence and artist’s models. They appear un-self-conscious, but I wander through the gallery inevitably questioning the selfdetermination of the sitters. The mystery of a poetically-positioned wrist, a lick of lipstick, an unlikely costume and a nod to the canon. The latter is particularly evident in Portrait #16, South Africa, 2016, in which two brothers with ecru-coloured skin reenact the pietà (or perhaps the photograph of Hector Pieterson) in a thicket of blossoming scrub.

For me, the triumph of the show is the understated symbolism of the plant-life. In Portrait #1, Rwanda, 2014, a child lies on the grass amidst fallen yellow blossoms. In Portrait #2, South Africa, 2014 a girl is brazenly naked but for a crown of hydrangeas and a pair of pale panties. In Portrait #14, South Africa, 2016, a pink boy crouches in the ash of a recent veldt fire.

‘1994’ is filled with honey-blonde fields, cool ponds and shadowy undergrowth that show nature raging quietly, inevitably and beautifully in the background. The colours are richly lit. Sunlight hits the earth head-on. It is verdant and edenic. Hugo transforms these politically post-apocalyptic places into pastoral utopias.

What happens when the evils are filed away as history? Life resumes – but there is a darkness reflected in these children that is perhaps theirs and perhaps Hugo’s.

Isabella Kuijers is a practicing artist and arts writer who contributes regularly to ArtThrob and other publications. She holds a BAFA and an English degree from Stellenbosch University.

Pieter Hugo's '1994' was on show at Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town from the 2nd June – 16th July 2016. This article was first published in the September 2016 edition of ART AFRICA magazine, entitled 'BEYOND FAIR'.

De beloofde generatie

Fotografie Pieter Hugo fotografeerde kinderen die zijn geboren na 1994, het jaar waarin Nelson Mandela in Zuid-Afrika tot president werd verkozen en in Rwanda genocide werd gepleegd.

Rosan Hollak

6 maart 2017

Dochter van Pieter Hugo, Zuid-Afrika, 2014

Foto’s Pieter Hugo/Cokkie Snoei

‘Zijn kinderen slechts onschuldige wezens? Ik denk het niet. Ze hebben een sterke overlevingsdrang en zijn niet alleen lief.” Sinds Pieter Hugo (40) – geboren in Johannesburg en tijdens de apartheid opgegroeid in Kaapstad – zelf kinderen heeft, kijkt hij anders naar de wereld. Daarvoor was hij een onrustige fotograaf die van hot naar her reisde en zijn camera richtte op mensen aan de zelfkant van de samenleving. Maar als jonge vader viel hem ineens op dat er overal kinderen zijn. „Voorheen zag ik ze eigenlijk nooit staan. Dat is nu anders, mijn blik is verschoven.”

Het ouderschap – Hugo heeft een zesjarige dochter en een driejarige zoon – heeft hem onzeker en kwetsbaar gemaakt.

„Je voelt je verantwoordelijk voor hun leven. Zeker in Zuid-Afrika waar de littekens van het kolonialisme nog zo voelbaar zijn.”

Zijn nieuwe blik op de wereld heeft Hugo ingezet voor het fotoproject 1994, genoemd naar het jaar waarin Nelson Mandela tot de eerste zwarte president van Zuid-Afrika werd verkozen. Het idee voor dit werk – portretten van kinderen die na 1994 zijn geboren in Zuid-Afrika en Rwanda – ontstond drie jaar terug, toen Hugo in opdracht voor een non-gouvernementele organisatie in Rwanda een fotoserie maakte van overlevenden van de volkerenmoord met hun voormalige vijanden.

„Ik fotografeerde in een aantal dorpjes tijdens de schoolvakantie. Er hingen veel kinderen rond. Om van ze af te zijn, maakte ik een paar foto’s van ze.”

Zuid-Afrika 2016

Rwanda, 2014

Rwanda, 2014

Eenmaal terug in Zuid-Afrika keek Hugo in zijn studio nog eens goed naar die beelden. „Ze hadden iets dwingends, ik bleef ernaar kijken.” Ook bestudeerde hij het portret van zijn driejarige dochter, poserend met een blauwe bloemenkrans, dat hij na terugkomst had gemaakt.

„Ik bedacht me dat deze kinderen tot op zekere hoogte vrij zijn. Opgroeiend na 1994 hebben zij een hele andere kijk op de geschiedenis dan de generaties voor hen.”

Zelf maakte Hugo 1994 heel bewust mee. „Mijn land zat in een grote overgang terwijl in Rwanda de volkerenmoord uitbrak. Alles stond op zijn kop.”

Welke relatie hebben kinderen tot het land waarin ze opgroeien? Die vraag bleef in zijn hoofd rondzingen. Hugo besloot meer kinderen te fotograferen, zowel in Rwanda als Zuid-Afrika. Hij liet hen poseren in het landschap. „Die natuurlijke omgeving is een soort psychologische ruimte. In beide landen heeft het landschap zo’n heftige betekenis. In Rwanda lagen in 1994 overal lichamen, de genocide heeft overal zijn sporen achtergelaten. Ook in Zuid-Afrika is de grond niet zonder betekenis. Daar vraag je je af: van wie is dit land? De grond is onteigend, er zijn grenzen getrokken die er voorheen niet waren.”

Symbolisch werk

Tussen 2014 en 2016 ging Hugo vier keer naar Rwanda om foto’s van kinderen te maken. Tussendoor fotografeerde hij kinderen in Zuid-Afrika. Hoe vond hij het om kinderen te portretteren, na al die foto’s die hij maakte van aidspatiënten, blinden, albino’s en rondtrekkende circusartiesten met hyena’s?

„Heel lastig. Ik zocht naar kinderen die een volledig gevormde persoonlijkheid hebben en met een confronterende blik de camera in durven kijken. Dat was moeilijk. Van de vele portretten die ik maakte, waren er telkens maar een paar goed. Ik heb eindeloos gefotografeerd.”

Veel van de kinderen die Hugo portretteerde hebben een volwassen blik.

Veel van de kinderen die Hugo portretteerde hebben een volwassen blik. Zoals de straatjongen die hij al in 2014 in Rwanda fotografeerde, liggend in het gras in een veel te grote jas. Maar er zitten ook kwetsbare portretten tussen, zoals het verlegen jongetje, dat met gehavende knieën en gekleed in een lila damesblouse, tegen een boom aanleunt.

Opvallend is dat hij de namen van de kinderen achterwege heeft gelaten. „Dat was een bewuste keuze. 1994 is een symbolisch werk, het gaat niet om het individu, maar om een groter verhaal.”

1994 van Pieter Hugo is t/m 18 maart te zien in galerie Cokkie Snoei in Rotterdam. cokkiesnoei.com.

Het fotoboek 1994 is uitgegeven bij Prestel, 112 blz., 43 euro.

Het Rijksmuseum toont t/m 21 mei 11 Zuid-Afrikaanse portretten uit de serie 1994 op de expositie Goede Hoop. Zuid-Afrika en Nederland vanaf 1600. rijksmuseum.nl.

Portrait # 16, South Africa

Portrait # 9, Rwanda

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten