November 20, 2015 10:52 am

Early Soviet photography at the Jewish Museum, New York

Ariella Budick

A powerful exhibition shows how fine photography distorted the harsh realities of the Soviet regime — but still made some brilliant art

Arkady Shaikhet: ‘Express’. 1939, gelatin silver print. Estate of Arkady Shaikhet©Courtesy of Nailya Alexander GalleryArkady Shaikhet: ‘Assembling the Globe at Moscow Telegraph Central Station’, 1928, gelatin silver print. Estate of Arkady Shaikhet©Courtesy of Nailya Alexander GalleryAlexander Rodchenko: ‘Pioneer Playing a Trumpet’, 1930, gelatin silver print. Estate of Alexander Rodchenko/Vaga©Centre Pompidou, ParisGeorgy Zelma: ‘Three Generations in Yakutsk’, 1929, gelatin silver print©Museum Ludwig, CologneArkady Shaikhet: ‘Red Army Marching in the Snow’, 1927–28, gelatin silver print. Estate of Arkady Shaikhet©Courtesy of Nailya Alexander GalleryGeorgy Petrusov: ‘Caricature of Alexander Rodchenko’, 1933–34, gelatin silver print©Courtesy of Alex Lachmann CollectionGeorgy Zelma: ‘Voice of Moscow’, 1925, gelatin silver print.©Courtesy of Alex Lachmann CollectionGeorgy Zelma: ‘Military Parade on Red Square’, 1933, gelatin silver print©Sepherot Foundation, Vaduz

When the Russian Revolution broke out in 1917, young artists exulted. They thronged to the vanguard and championed art’s capacity to stun. Just as political leaders had toppled the establishment, creative revolutionaries aimed to knock the visual world off balance. Nearly a century later, the art establishment is still riding that first wave of exhilaration, still charmed by photographers who achieved a bright new way of looking.There’s something simultaneously poignant and terrifying about The Power of Pictures, a beguiling round-up of propaganda designed to bolster the Soviet Union in its early years. The talent on display is tremendous, and the vision duly uplifting. We see orderly cities, impressive parades, majestic factories and awesome lightbulbs. We do not see emaciated peasants, executed dissidents or enslaved prisoners. These old-fashioned downers found no place in the photographer’s formalist experiments, or in society’s speeding thrust toward utopia.

It’s odd that a show ostensibly about political art is so narrowly focused on aesthetic innovation. In an introductory wall text, curators Susan Tumarkin Goodman and Jens Hoffmann write that the first Soviet photography still has a bracing effect today, reminding us “that to maintain a connection between art and politics is a matter of urgency”. The curators find it less urgent to point out that those revelations depended on stunningly wilful blindness. The first Soviet photographers thought they were teaching the world to see; instead they were teaching it not to.

Until his career was quashed by Stalin in the 1930s, Alexander Rodchenko waged by far the most sophisticated battle to uncork the worker’s potential. Trained as a painter, he hitched his pioneering vision to the Bolshevik programme, and by 1921 had denounced painting altogether as a relic of bourgeois decadence. He styled himself as a sort of visual engineer, furnishing the post-revolutionary society with uncomfortable chairs, techno-teapots and, best of all, unsettling photography.

His Leica pitched buildings and people into disorienting angles and baffling close-ups, jolting his audience into what he hoped was a revolutionary perspective. His camera transformed a woman standing on a flight of stairs into a diagonal stroke across parallel lines, and turned a view of a Moscow courtyard into a cacophony of giddy geometries and abrupt changes in scale.

He treated his own mother’s face as terrain ripe for exploration, homing in on a clash between flesh and fabricated materials. The doughy mounds of her cheeks, nose and chin rub against the glass and metal of her spectacles, which in turn cast confusing shadows on her skin. Only a few years later, the Dadaist Raoul Hausmann wrote: “After all, the smoothness, the glow or the limpness and wrinkles of a face are formal expressions of what that face has become. These forms alone represent something.”

Rodchenko’s grotesque “Pioneer With a Bugle” (1930) captures the teenage instrumentalist from below, his cheeks like two enormous puffed-up hemispheres below a jutting cliff of forehead. The perspective demands viewers’ active participation; they must labour to read the abstract arrangement of curved surfaces and brass tubing as a human face making sound.Rodchenko’s public misread his intentions, seeing “Pioneer with a Bugle” and a companion photo, “Pioneer Girl” (1930), as insultingly perverse distortions. A letter published in the journal Proletarskoe Foto (“Proletarian Photography”) criticised Rodchenko for “disfiguring the young, healthy face of the pioneer” and transforming it “into the face of a freak”.

That sort of commentary was ominous. Before long, he stood accused of “bourgeois formalism”, the all-purpose sin that suggested he was out of step with the masses (or with the bureaucrats, at any rate). By 1934, the government decreed that only socialist realism was fit for proletarian consumption, and Rodchenko complied. His pictures of the White Sea Canal, a 140-mile waterway constructed in 500 days, celebrated the miraculous feat of human engineering, but elided the human cost. Tens of thousands of political prisoners died digging the ditch with shovels but no heavy machinery. Never mind: that took place outside the frame.

Rodchenko wasn’t the only photographer to veil the regime’s nefariousness with a scrim of progressive aesthetics. That same year, Georgy Petrusov “documented” collective farms, where peasants and landowners died by the millions. “Lunch in the Field” (1934) depicts happy agricultural workers feasting in a meadow idyll. The image, taken from a godlike vantage point, draws attention to its formal daring. Petrusov also shot marmoreal peasant women from below, outlining their heroic heads against the sky. Elizaveta Ignatovich (married to Boris, also prominent in the show) depicts an artisanal bakery where a white-clad worker is dwarfed by dozens of ripe loaves. The message of purity and abundance trumps the reality of mass starvation.

Some of the photographers buckled down and had long careers; others buckled under and became victims of the regime they served. The same story could be told about writers, scholars and composers. Their work glamorised a vicious political system, and the glamour endures long after the system withered away. The curators acknowledge this falsity, especially in a section called “Staging Happiness”, but they seem seduced by it nevertheless.

As the show moves into the mid-1930s, it’s hard to miss the parallels between Soviet photo virtuosi and their Nazi counterparts. Rodchenko’s “A Jump Into Water” (1934), capturing a diver magically splayed in mid-air, bears a remarkable resemblance to Leni Riefenstahl’s treatments of the same feat. Her picture of the gorgeously sinewed javelin thrower at the 1936 Olympics could practically be an homage to Max Penson’s earlier version from 1928. And Georgy Zelma’s “Military Parade in Red Square” (1933) could be mistaken for a still from Riefenstahl’s film The Triumph of the Will, which documented the 1935 Nazi rally in Nuremberg.

The formal similarities point up how differently we treat German and Soviet art from that period. Three years ago, when the Museum of Modern Art mounted an exhibition of sports photography from the 1930s, it scrupulously underlined the point that Riefenstahl’s career “is marred by her role as part of the propaganda machine of the Nazi party . . . One cannot consider [her] innovations without acknowledging the violent political apparatus that supported them.” At the Jewish Museum, the disclaimers are more perfunctory, by-the-way remarks in the context of a show about photographers who made mass murder and misery look formally interesting and rather grand.

‘The Power of Pictures: Early Soviet Photography, Early Soviet Film’, Jewish Museum, New York, to February 7.

TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 26, 2008

Two Soviet books from the 1939 New York World's Fair

The other booklets in this series might be tempting to pick up if found for under $5.00 but for purposes of the photography, they are skimpy and would probably be uninteresting for the average photobook enthusiast. I paid $15 for this copy and I see many others listed online starting around $20. If anyone has the complete set and could recommend another title that is equally as enjoyable as this parachute booklet, please let me know via the comments section

This past weekend was the Greenwich Village Antiquarian Book Fair at PS 3 in NYC. I do not usually find much in the way of bargains at these events since they are full of book dealers who mostly price according to ABE listings but a friend of mine did find a shrink-wrapped copy of Robert Adams Our Lives and Our Children published by Aperture in 1984 for a mere $25.00. Seems there are some very good prices still to be found even through the dealers.

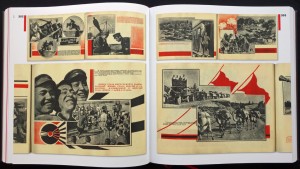

My only find was a small booklet that appealed to my love of design. It is called Parachute-Jumping and Gliding: Popular Soviet Sports. Upon seeing the cover, I was hoping that this 32 page booklet would be like a mini-version of the now famous USSR in Construction parachute issue (SSSR na stroike, 1935 Issue #12) but it is nothing in comparison.

Parachute-Jumping and Gliding: Popular Soviet Sports was a part of a 30 booklet series aimed at revealing the great achievements of the Soviet Union . Published in English these booklets were distributed at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. The topics cover everything from collective farming to youth sports, livestock to leisure activities in the Soviet Union . Each is approximately 5 by 4 inches and mostly comprised of text interspersed with a few illustrations.

This one in particular drew my attention because it contains two illustrations that combine photography and design into graphs meant to show records held in both gliding and parachuting by Soviets. (Since there are so few illustrations in this booklet I have shown all of them in my composite above). The other enticing features are the two color cover graphic and the letterpress interior.

The other booklets in this series might be tempting to pick up if found for under $5.00 but for purposes of the photography, they are skimpy and would probably be uninteresting for the average photobook enthusiast. I paid $15 for this copy and I see many others listed online starting around $20. If anyone has the complete set and could recommend another title that is equally as enjoyable as this parachute booklet, please let me know via the comments section

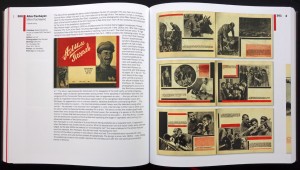

Staying within the topic of Russian photobooks, I found an interesting title several months back in a junk warehouse here in Brooklyn called Soviet Photography 1939. I do not know much about this book as with extensive research I have only found one other reference online through a dealer of Russian books.

Soviet Photography 1939 contains 66 photographs and has beautiful burgundy hard covers with gold colored, debossed titles and a decorative-edged spine. The cover is very reminiscent of high school yearbook designs common from the 1930’s here in the United States . The printing was accomplished through letterpress so the reproductions have a nice presence on the crème-colored paper. It was published by the State Publishing House for Cinematographical Literature in Moscow .

After a three page introduction touting the greatness of Soviet photography (and ideology) the book proceeds with photos typical of the Soviet State Soviet Union . Most of what follows are examples of photographs that have been so extensively retouched that they tend to look more like paintings than anything meant to represent reality. That being said, there is something to the infectious idealism portrayed with all Soviet propaganda that makes this another enjoyable fantasyland of harmonious relationships between Soviet peoples, their great accomplishments, and their clean stewardship of the land.

There are a few clues with this book that would indicate that is was published as a souvenir from the New York World’s Fair like the small booklet on parachuting I described above. The first being the publication date of 1939 but also the introduction is in English instead of Russian. The last and most tenuous being that I found it in Brooklyn within 7 miles fromCorona Park

Accounting for inflation of the cost of living over the past 70 years, I am not complaining that these gems set me back $20.00 in total.

MONDAY, NOVEMBER 23, 2015

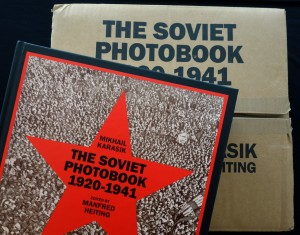

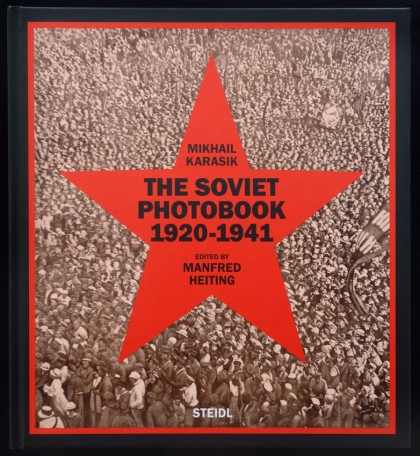

Book Review: The Soviet Photobook 1920-1941

|

The Soviet Photobook 1920-1941. Edited by Manfred Heiting and Mikhail Karasik. Steidl, 2015. |

The Soviet Photobook 1920-1941

Reviewed by Colin Pantall

Edited by Manfred Heiting and Mikhail Karasik

Steidl, Gottingen, Germany, 2016. In English. 636 pp., 10½x11¼".

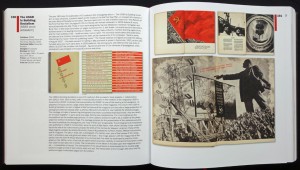

The Soviet Photobook 1920-1941 is a comprehensive heavyweight affair that gives a history of the greatest period of photobook production ever undertaken. It’s a serious book with serious texts on a serious subject. And it’s astonishingly illustrated with spreads taken from publications few of us ever knew even existed.

The book is divided into 17 chapters that run more or less chronologically from 1921 to 1941. Right from the first chapter (Photography and the New Religion), we’re into revolutionary design, images constructed in the name of the revolution.

We rattle through the chapters with Rodchenko putting in an early appearance in chapter two,The Word and the Photograph. But as well as seeing the cover of Mayakovsky’s famous About This: To Her and to Me, we see the 8 photomontages inside, with dinosaurs, peanuts and parakeets, all fair game for Rodchenko’s scissors.

|

The Soviet Photobook 1920-1941. Edited by Manfred Heiting and Mikhail Karasik. Steidl, 2015. |

There’s the propaganda of The Lessons of Constructivism chapter and then we’re ontoIndustrialization and the epic layouts of El Lissitzky’s first propaganda album, The USSR is Building Socialism, a photobook where double-page montages are "printed in two colors, black and red. The introduction of short slogan-like texts into the photomontages make these pages look like posters."

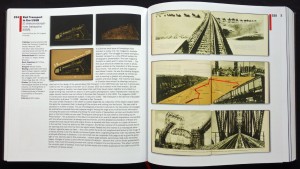

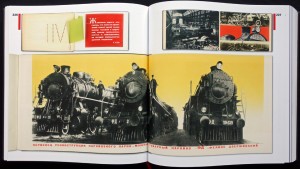

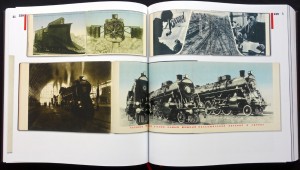

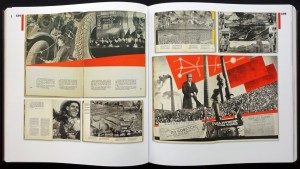

The army, the navy, trains, dams, steel mills, farming; it’s a trawl through an idealized and thoroughly happy Communist past. But it never gets repetitive or boring. Take the book New Rail Transport Technology; this was the first book about Soviet rail transport and it's relatively restrained, its mix of sober shots of bridges, tracks and signals are cut with a full-bleed picture of a live platform, station clock in the foreground, life going on in the most relaxed and casual manner imaginable.

|

| The Soviet Photobook 1920-1941. Edited by Manfred Heiting and Mikhail Karasik. Steidl, 2015. |

The chapter on Photography and Pictographs is a revelation in how "Dry statistics and tedious topography were converted… into a work of art; they are treated as geometrical abstract pictures." The writer, Mikhail Karasik, is talking about Moscow is Being Reconstructed here but the same also applies to The USSR’s Five-Year Plan, which glories in a series of pictographs because "Pictorial statistics provided the simplest and most readily available means of presenting information in a country whose citizens were mastering the basics of economics at the same time as they were learning to read and write."

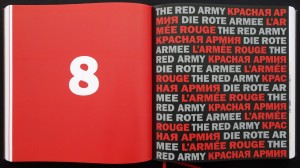

There are the glorious books celebrating 10 years of the Soviet Union (including the Parr and Badger featured Uzbekistan volume with its Stalin shaped window) and then it’s the Red Army where the full cult of the militarized individual finds fettered reign in a whole series of staged portraits, panoramas and battle scenes. The final chapters look at Soviet Cinema, the books of the Soviet Pavillion at The World’s Fair in New York 1939-1940, and the masters of Soviet photography.

|

| The Soviet Photobook 1920-1941. Edited by Manfred Heiting and Mikhail Karasik. Steidl, 2015. |

The most tender chapters are Soviet Women Soviet Youngsters and The Land of Happiness; in the former there’s Protection of Mother and Child in the Land of Soviet, a book that ends with "a bronze Lenin apparently waggling his hand at a laughing child." In the latter we get to go to Transcaucasia and enjoy The Soviet Subtropics, a region where "creative work was already in full swing aimed at producing the wonderful multi-coloured vegetable carpet of the Soviet Florida."

The book spreads are accompanied by detailed and informative text that provides the background context for the photographers, designers and publishing houses behind this wealth of printed material. Connections are briefly (sometimes very briefly — it’s a book written with a ‘Motherland’ perspective) made to broader social movements and the main political events that were taking place in the Soviet Union between 1920 and 1941. There is also the narrative of how design and photobooks developed between these years, with montage and constructivism passing to photojournalism and reportage before ending up at the end game of fully fledged social realism complete with its heavy handed retouching of both faces and facts.

|

| The Soviet Photobook 1920-1941. Edited by Manfred Heiting and Mikhail Karasik. Steidl, 2015. |

Informative though this is, the density of the information is sometimes hard to digest for readers (like me) who are unversed in how the intricacies of Marxist, Stalinist, and Leninist thought played out in publishing. At times assumptions are made about the background knowledge the reader has both of book publishing and political history, and it becomes difficult to see the big picture due to the mass of detail. The Soviet Photobook is also a history book, and this idea is compounded by the list of photographers, artists, and writers to be found at the back. But it would have been good to add a simplified timeline of key political and publishing events. Though it’s made for easy viewing, it’s not made for easy reading.

An additional frustration (and the major irony of a book that has propaganda and the easy dissemination of information as its major theme) is that the text is laid out in great un-paragraphed and untitled blocks that make it difficult to navigate. And in this sense the book is under-designed and could have taken some lessons from the chapters on infographics in how to make information as accessible as possible.

|

| The Soviet Photobook 1920-1941. Edited by Manfred Heiting and Mikhail Karasik. Steidl, 2015. |

That is a minor quibble though, because dig deep and focus hard and you will find whatever it is you are looking for, both in the text and in the images. And it’s the images that matter here. They are stunning, and well balanced with no over-emphasis on a particular era or theme. This is a book you can return to again and again (both to the words and the pictures) and you will always find something new. It doesn’t quite have the easy page-by-page referencing style of The Photobook: A History, but it more than makes up for that in the generosity of the spreads. It is simply gorgeous to look at with an authority to match.—COLIN PANTALL

/ Thomas Wiegand

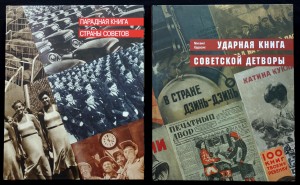

Ein Fotobuchkontinent wird neu entdeckt

The Soviet Photobook 1920 - 1941

Dass es in der Sowjetunion in den zwanziger und dreißiger Jahren eine außerordentlich reiche avantgardistische Fotobuchkultur gegeben haben muss, war nicht zuletzt durch die Fotobuch-Bücher zu erahnen, in denen immer wieder einzelne sowjetische Fotobücher vorkamen.Und es gibt dazu schon eine Arbeit des Buchkünstlers und -forschers Mikhail Karasik, aber dies nur in Russisch, was den Leserkreis einschränkt.* Nun wird dieses Standardwerk von einer völlig überarbeiteten und erweiterten Fassung in Englisch abgelöst. Damit sind die Voraussetzungen gegeben, dass man den bislang nur schemenhaft erkennbaren Fotobuchkontinent in aller Deutlichkeit vor sich liegen sieht. Gefördert von Stalin durften/mussten die russischen Avantgardisten an illustrierten Büchern mitwirken, was heute deren besondere Qualität und Relevanz ausmacht. Kein Aufwand wurde gescheut, um diese Werke zu gestalten: Montagen, Farben, Prägungen, Faltungen, Metalleinlagen… Die Bücher waren Meisterleitungen und dienten der Propaganda vor allem im Inland, zuweilen aber auch für das Ausland, so ein größeres Konvolut von in Englisch getexteten Publikationen der UdSSR zur Weltausstellung in New York 1939. Zudem gab es mit dem Magazin USSR in Construction ein kontinuierlich die Ideen des Kommunismus und mit ihnen die Ästhetik der russischen Avantgarde in englischen, deutschen, französischen und spanischen Auslandsausgaben verbreitendes Medium.

Das dicke und schwere, von Manfred Heiting herausgegeben und gestaltete Buch gibt einen in 17 Kapitel (Industrialisierung, Staatsjubiläen, Rote Armee etc.) geordneten Überblick mit 165 einzelnen Werken. Diese mögen seinerzeit große Auflagen gehabt haben, doch heute sind sie sehr selten und im westlichen Ausland praktisch nicht erreichbar. Von daher ist das üppig ausgebreitete Material an Reproduktionen von unschätzbarem Wert, denn die vorgestellten Bücher wird man normalerweise entweder gar nicht oder nur unter großen Schwierigkeiten (Recherche, Zeit, Genehmigungen, finanzieller Aufwand) zu Gesicht bekommen. Autor Karasik lebt in St. Petersburg, hat sich jahrelang mit dem Thema beschäftigt und kennt die Materie aus dem Effeff. Neben einer zusammenfassenden Einleitung hat er für jedes Buch eine kurze Würdigung und selbstverständlich die bibliographischen Daten (in englischen Übersetzungen) beigesteuert. Marina Orlova hat für den Anhang ein kurzes, aber hinsichtlich der Menge der Namen und Begriffe gehaltvolles Glossar der beteiligten Fotografen, Designer, Textautoren und Politiker erarbeitet. Von Heiting stammt nicht nur das Vorwort, sondern auch und vor allem das Layout. Für den Einleitungsteil und die Kapiteltrennungen hat er den Stil der stalinistischen Fotobücher aufgenommen, sonst aber für eine sachlich-dienende, aber immer kraftvolle Gestaltung gesorgt, die die Möglichkeiten zur Präsentation von Fotobüchern (nach Deutschland im Fotobuch und Autopsie) erneut erweitert. Wie schon in Autopsiewerden die Bücher ohne Gebrauchsspuren in einer dem Neuzustand angenäherten Form abgebildet.

Propaganda als Mittel der Politik führte vor allem in totalitären Regimes zu aufwändigen Druckwerken: die faschistischen Regierungen in Deutschland, Italien, Spanien und Portugal nahmen sich nur ausnahmsweise die Ästhetik der Russen zum Vorbild. Zu einer versachlichten Bildsprache und deutlich vereinfachten Produktionen kam es nach 1945 in der Sowjetunion selbst und in Anlehnung daran in anderen sozialistischen Staaten wie der DDR, Polen und der CSSR. Wie sich die Propaganda in chinesischen Fotobüchern manifestiert hat, zeigtThe Chinese Photobook von Martin Parr und WassinkLundgren. Auf Basis der Themen und Ästhetik der Stalinzeit hatte sich ein Standard herausgebildet, der in unterschiedlichen Ländern immer wieder neu durchdekliniert wurde und der lange wirksam blieb (was das Feld für weitergehende Untersuchungen öffnet).

Die stalinistische Politik war nicht menschenfreundlich. Die Bücher, die während dieser Zeit zur Darstellung ihrer Ziele und Erfolge erschienen, zeigen in jeder Beziehung und auf allerhöchstem Niveau ein anderes Bild. Karasik und Heiting gebührt das Verdienst, das Material für eine eingehende Diskussion dieser besonderen Spielart der Propaganda aufbereitet und in Form dieses fulminanten Standardwerks bereit gestellt zu haben. Auch wer sich für Fotobücher und politikgesteuerte Publizistik nicht interessiert, wird lange brauchen, die unglaubliche Fülle avantgardistischer Fotografie und kongenialen Designs verarbeiten zu können!

Parachute Jumping And Gliding Popular Soviet Sports

Moshkovsky, Major V.

Publication Date: 1939

1st edition, near fine condition, stiff pictorial wraps, published by The Foreign languages publishing House, Moscow, 32 pages. A brief history of Parachute Jumping, and Glider Soaring sport clubs in the Soviet Union prior to World War II. With a list of International Parachute Jump records held by Soviet Parachutist, and a list of International Long distance records held by Soviet Glider Pilots. Illustrated with photographs, and drawings.

Soviet Photography 1939

Borodin, M. ; Harvey, N. ; Mikulin, V. ; Rogozhansky, M. (editors)

Published by State Publishing House for Cinematograpical Literature, Moscow, 1939

Pre-Second World War propaganda publication with photographs by Rodchenko, Novitsky, Alpert, Markov, Kislov, Petrov, Strunnikov, Shagin, Loskutov, Kudoyarov, Kuleshov, Khalip, Bernstein, Granovsky, Diament, Ignatovich, Alperin, Friedland, Prekhner, Oshurkov, Nappelbaum, Skurikhin, Garanin, Shaikhet, Shimansky, Petrusov, Prekhner, Andreyev, Petrusov, Tuvin, Prekhner, Kuleshov, Shterenberg, Fishman, Zelma, Debabov, Shtertser, and Langman. Text in English. Printed in the Soviet Union, by Gosnak, Moscow. Includes 31 leaves of plates with approximately 60 images. One page loose, staples in binding rusty, bumps to one corner and tail of spine (not effecting photographs), some pencil marks to margins. Original burgundy leatherette boards.