Pictures of People

(ISBN 10: 0870704389 / ISBN 13: 9780870704383 )Nixon, Nicholas, Illustrated by Nicholas Nixon Photos

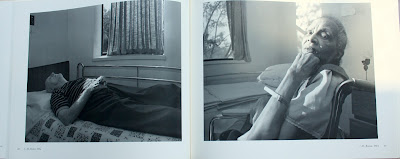

Fn soft cover copy from the 2nd printing, apparently unused. 126 pp. Illustrated introduction by Peter Galassi, 85 Photo reproductions, Chronology, and Bibliography. Exceptionally communicative B/W images from various Nixon informal portrait projects. Using an 8 x 10 view camera and contact printing Nixon produced images of surprisingly convincing naturalness and immediacy. A determined effort was made to preserve the beautiful detail of the original photographs by printing original size plates in tritone from negatives prepared by Richard Benson.

There are two apparently polar but equally valid ways of looking at Nicholas Nixon's photographs. His images are remarkable demonstrations of how the traditional (and by now archaic) tools of the medium - a view camera, black-and-white film, contact prints - can be used to venture into uncharted artistic territory. At the same time, they concentrate on subjects - the poor, the elderly, the mortally ill - that align the work with photography's tradition of socially concerned documentation.

Within the esthetic debates of the last several years, formal concerns in art have often been seen as separate from, if not antithetical to, social consciousness. But Nixon, more than any other photographer of our time, forces us to consider that the two approaches are more interconnected than one might suspect. As Peter Galassi, the curator of an exhibition of Nixon's work of the last 10 years that opens Thursday at the Museum of Modern Art, says of the photographer's activity, ''Making pictures has become a way of finding a path to the heart.''

Nixon's photographs do not aspire to revamp the essential assumptions of documentary photography. As did Lewis Hine, Dorothea Lange and countless other socially concerned photographers of this century, he relies on the photographic image's ability to convince us that what we are seeing is the truth. Like them, he assumes that seeing is enough to provoke indignation and action. But Nixon's faith in the photograph's powers of persuasion goes even further; unlike Hine or Lange, he feels no need to provide captions to tell us what we are seeing. At a time when many critics have concluded that the social-documentary tradition is exhausted, its efficacy worn down by bathos and repetition, Nixon's ability to make images that move us is all the more remarkable.

The 125 prints in ''Nicholas Nixon: Photographs of People'' are arranged in groups that roughly correspond to the course of the photographer's work. The earliest images on view, under the heading ''People,'' date from the late 1970's and early 1980's and depict groups of children, teen-agers and adults at leisure, lying on the beach or standing in front of their homes. Several show families gathered on porches. Judging from the meagerness of the clothes they wear and the houses they inhabit, most live in poverty. More than half the people we see are children, and the contrast between their open faces and the often downcast visages of their parents and grandparents gives the photographs much of their poignancy.

At the same time, however, these images are astonishing for the complexity of their pictorial organization. As many as half a dozen people are arrayed within their borders, close to the camera and behaving as candidly as they might in common snapshots. But the photographer gives them a sense of shape and proportion that makes what is fortuitous seem inevitable. The formal grace and ease is all the more remarkable inasmuch as Nixon made the photographs with an 8-by-10-inch view camera, an imposing instrument that one would think to be too balky, slow and conspicuous for such an approach.

Moreover, and despite their wealth of descriptive detail, Nixon's contact prints are not beautiful in any conventional sense. Their unpreposessing black-and-white hues are without any seductive tint or tone. Their range of grays is less consistent and less dramatically crafted than can be found in the prints of Ansel Adams. But their relative roughness turns out to be an advantage. They have an immediacy and ingenuousness quite removed from the sense of calculation characteristic of Adams's images.

In the show's catalogue, Mr. Galassi has written that the photographer's ''pictorial innovations, although masterful and even breathtaking, seem less to open a new territory for others to explore than to realize an opportunity created by earlier work. Photographic tradition, in its headlong, spendthrift course, had forged a consensus that the opportunity was used up.'' The wonder of Nixon's pictures, the curator concludes, is that they prove this consensus wrong.

After dealing with people in public spaces in a way that redefined ''street photography,'' Nixon moved inside. Between 1983 and 1985 he photographed in a nursing home, recording the elderly residents in portraits that scrutinize each one individually. Isolated in the frame, seemingly heedless of the photographer's presence (although Nixon again used his large, obtrusive camera), the subjects seem to mirror the conditions of their lives. But as unlike the group portraits as these pictures are, the two series have one thing in common: they depict their subjects without prejudice. They neither flatter them nor disdain them; they indulge in neither sentiment or irony.

This refusal to take sides is perhaps the major source of tension in Nixon's photography, what gives it its ''edge,'' so that a viewer is forced to feel uncomfortable in its presence. The sense of pictorial implacability - evident in Nixon's earlier pictures of city buildings, which the museum exhibited in a 1976 one-man show - can seem a virtue at a time when sentimentality and romanticization threaten to pervert the possibilities of meaning in photographs. This surely was true in the mid-70's, when Nixon wrote one of the most striking single-sentence artist's statements ever published: ''The world is infinitely more interesting than any of my opinions about it.''

Yet the refusal to give in to what Mr. Galassi calls ''pictorial and moral cliche'' should not be mistaken for a lack of concern or care - an error that critics of Nixon's ''formalism'' may finally be forced to admit when they see his most recent body of work, sequences of pictures of people with AIDS. These images, which conclude the exhibition and which are the focus of an ancillary show at the Zabriskie Gallery that opens on Friday (724 Fifth Avenue, through Oct. 22), are the most searing, sobering and unforgettable photographs of Nixon's career. They may also be the most powerful images yet taken of the tragedy that is AIDS.

In the museum's show there are four series on view, ranging from 4 to 12 images each. The subjects include gay men, a woman and a male hemophiliac. The photographs, taken over a period of months, chronicle both the visible signs of the progress of the disease and the inner torment it creates.

The result is overwhelming, since one sees not only the wasting away of the flesh (in photographs, emaciation has become emblematic of AIDS) but also the gradual dimming of the subjects' ability to compose themselves for the camera. What each series begins as a conventional effort to pose for a picture ends in a kind of abandon; as the subjects' self-consciousness disappears, the camera seems to become invisible, and consequently there is almost no boundary between the image and ourselves.

In the case of Thomas Moran, whom Nixon photographed from August 1987 until shortly before his death in February, the progression from posed portrait to tacit acceptance of the camera's presence is especially vivid. In the sequence's first image, mother and son look out at us, embracing and apparently consoling each other. At the sequence's end, the young man's eyes again look in our direction, but they seem focused on infinity. Here, and in the other sequences, Nixon fashions complex meanings from one of the most basic elements of photographic portraiture, the subject's gaze.

In their openness to the emotional potential of photographs, Nixon's portraits of people with AIDS show the influence of another side of his picture-taking - that involved with his family. Since the mid-1970's, he has taken yearly group portraits of his wife and her three sisters, and in the mid 1980's he made a number of images of his two infant children. These images, which serve to temper the otherwise sobering tenor of the exhibition, are filled with vitality and a sense of the future. They also represent the nearest the photographer gets to expressing conventional sentiment.

The family photographs provide a precedent for the AIDS portraits in terms of both their methodology and their emotional resonance. The much-published series of yearly group portraits, for example, may have inspired Nixon to work in sequence in his AIDS images, as a way of showing the passage of time. Like the pictures of his children, the AIDS portraits are essentially private moments made public, but with a difference: the family pictures have no wider social consequences. As a result, they seem less significant - and surely less demanding - than Nixon's pictures of the poor, the aged and the ill.

Compared to other attempts to photograph current social problems - notably, Rosalind Solomon's ''Portraits in the Time of AIDS,'' shown in June at the Grey Art Gallery - Nixon's pictures seem to be translucent. They are largely without any stylistic inflection that would divert our attention from the subject to the photograph itself. Nor do they aim for dramatic effects of the kind W. Eugene Smith felt were necessary to capture the public's attention.

While Mr. Galassi's remarks at the close of his catalogue essay that ''as the work has matured it has grown closer in spirit to Diane Arbus's work,'' the more obvious precedent for Nixon's approach is Walker Evans - specifically the Evans who took the portraits found in ''Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.'' Like Evans, Nixon has perfected a style that seems to be no style at all, so that for a brief and magical moment what he shows us, and how he chooses to shows it, appear synonymous.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten