Album of the years: can photo albums survive the digital age?

An evocative survey of photo albums captures the history of American photography – and asks whether we'll ever impose order on our sprawling digital collections

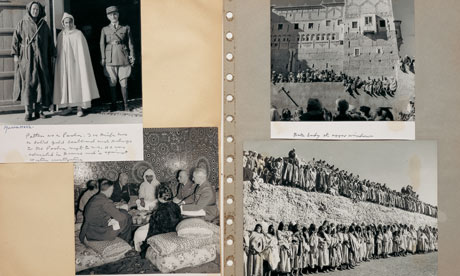

Compiled by Beatrice Banning Ayer Patton; photographed by

George S Patton Jr from second world war albums, 1941-1947 ... taken from

Photographic Memory: The Album in the Age of Photography. Photograph:

Aperture/Library of Congress

"When you hold a photo album, you sense that you are in possession

of something unique, intimate, and meant to be saved for a long time,"

writes Verna Posever Curtis in the introductory essay to Photographic Memory: The Album in the Age of

Photography. "As you turn the pages and look at

the images, you imbibe the maker's experience, invoking your imagination and

prompting personal memories."

I've been wondering about this reflection ever since I first read

it a few weeks ago, mainly because this is not what the photographic album –

save for my own or my family's altogether more haphazard collections of images –

evokes in me. When I see a photographic album, the first thing I think of is

order: a disciplined mind; a systematic approach; a rigour that is altogether

not my own; that is, in fact, the opposite of my more scattergun approach to

images and memories. Indeed, I often feel there is something lifeless about the

carefully composed photographic album that may be to do with the editing

process: the elimination of the random, the accidental, the blurred and the

botched photograph.

If truth be told, my imagination and personal memories are more

likely to be evoked if I trawl though an old box of anonymous family

photographs, those piles of fading, crumpled, almost discarded things that end

up in car boot sales and flea markets and remind us that most lives go unmarked

and unremembered save for these unmoored images that have floated free for their

context and thus are imbued with a quiet but resonant sense of

mystery.

Then again, I am not a curator and Curtis is. She oversees the

photography and print collection at the Library of Congress and has trawled the

archives there for her book selection. As its title suggests, the albums on

display in Photographic Memory: The Album in the Age of Photography are no

ordinary volumes. They are, in fact, a kind of potted history of mainly American

photography. The albums are arranged under loose headings: Souvenirs and

Mementos; Presentations; Documents; Memoirs; and, perhaps most intriguingly,

Creative Process. They range in style and subject matter from Edward H Harriman's documentation of a scientific

study carried out in Alaska in 1899 at the height

of the gold rush to an extensive family album complied by the photographer and

film-maker Danny Lyon in 2008 and 2009.

In between, there are albums compiled by explorers, historians and

anthropologists as well as celebrity photographer Phil Stearn, musicologist Alan Lomax, Nazi propagandist Leni Riefenstahl,

and several other well-known image makers such as Walker Evans, W Eugene Smith and Jim Goldberg. The book

shows how technology - and, in particular, the coming of the instamatic and the

Polaroid - impinged on the style and the function of the photo album, often

allowing photographers to use them as a kind of prototype for the more stylised

photography book that would inevitably follow. It traces, too, how the photo

album has moved from being a historical record, whether of an Alaskan

exploration or a celebration of the Hitler Youth movement or even a party held

for President Kennedy by Frank Sinatra, to a kind of artist's book through

which, as is the case with Duane Michals or Goldberg, we are given access to a

creative diary or a glimpse of the way an artist works.

Photographic Memory: The Album in the Age of Photography is also

perhaps an elegy for the photo album. Many of the albums included here are

testaments to the art and craft of personalised book-making, one-offs that seem

almost anachronistic in the age of the download and the hard drive. If the

photography book is currently thriving as a medium, the old-fashioned photo

album does seem very much a thing of the past.

And yet for all that, as Curtis puts it, "many people desire a

physical object that can be held, paged through again and again, and shown to

others". For that very reason, the photo album has given way to the

self-published photobook, an online publishing phenomenon that means you or I

can create our own album using preordained templates and printed from digital

files. (I have addressed the self-publishing phenomenon

here.) The photobook, though, is not really the

equivalent of the photo album: rather than a painstakingly compiled one-off, it

can be reproduced to order and it is often wilfully non-crafted in the manner of

a lo-fi musical recording.

"It is difficult," writes Curtis, "to predict whether people will

be fully satisfied with the textural uniformity of these manufactured books

comprised of digital images made on demand through a commercial

service."

Using the artist/book maker Paolo Ventura as an example, Curtis is optimistic that the

photo album will survive in some form or another. Ventura makes small-scale

created tableaux using tiny models which he then photographs and incorporates

into his large-scale art works. He records every stage of his very postmodern

creative process in a series of old-fashioned, hand-crafted albums. "In the

end," concludes Curtis, "an abiding desire to tell a story with photographs will

keep some form of album-making alive." Despite my hopeless aversion to order, I

hope she is right.

A Closer Look -- Photographic Memory by Photo-Eye

|

| Photographic Memory -- Edited by Verna Posever Curtis |

New from Aperture, Photographic Memory: The Album in the Age of Photography, edited by Verna Posever Curtis, is a look into the art of the photo album. Culled from the vast collection of albums in the archives of the Library of Congress, Photographic Memory organizes the 24 featured albums into five categories, Souvenirs & Mementos, Presentations, Documents, Memoirs, Creative Process. The book opens with an essay on the history of the photo album and includes texts on the status of the album in the digital age, the preservation of these precious objects, notes and an index. Each album presentation opens with a photograph of the closed book facing the story of the album and its compiler and how it came to be in the collection of the Library of Congress. The types of albums contained within run the gamut: political mementos from US campaigns, Nazi propaganda, precursors to landmarks in the history of photobooks like Let Us Now Praise Famous Men and notebooks complied from the photographs of Dorothea Lange, documents of expeditions, the personal war album of General Patton, family albums and even a collection of photographs of beautiful, sleek and eerie looking airships.

|

| from Photographic Memory |

|

| from Photographic Memory |

The cohesion of this collection is found in the wonderful manner in which the albums are presented. Photographing the books as a whole, the images show full page spreads, allowing the albums to lay open as they would if viewed on a table. Page layouts vary -- some featuring a grid of images while others align the seam of the album with the gutter of the book, making them feel even more alive. This technique has also been employed with much success by the Books on Books series, and is the ideal way to communicate the object beyond the images.Photographic Memory celebrates some of the most resonate qualities of these constructions -- the hand of the maker in the album and the shear physicality of the object. Shown in this manner, the albums appear more tactile and personal, full of handwritten captions, notes and illustrations, discoloration and foxing, photocorners, paper clips and a variety of bindings in an array of conditions.

Some of my personal favorites -- the handwritten narration and illustrations accompanying George F. Nelson's Alaska; the gorgeous detail work and ornamentation in Jean Anthony Varicle's Sketches of the Northland, including the handmade caribou skin cover, complete with magnificent hand lettered titles and bark and real gold embellishments; the stunning and personal family album of Danny Lyons, innovative in its design and reproduced here with the handwritten captions just large enough to be readable; the beautiful images from the private album of Max Waldman called Color Town; the tiny contact prints that make up the almost haphazardly arrangement of images in Alan Lomax's Spanish Photo Notebooks, his first real effort to visually document his historic field-recording trips. Though Photographic Memory only shows a few pages from each of these fascinating volumes, it is a book that encourages return viewings. I would imagine that a number of the albums in this book could do well as full reproductions, and makes the case for the album to be considered a unique genre of book art.

|

| from Photographic Memory |

See also

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten