1958 Joden van Amsterdam, de Bezige Bij, Netherlands

Leonard Freed: An American in Amsterdam ...

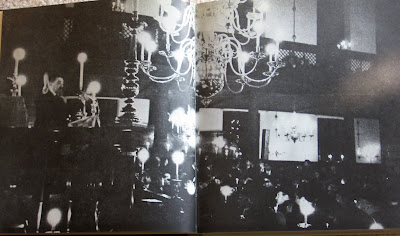

Freed’s first official book, entitled Joden van Amsterdam, appeared in 1958. Whether by chance or grand design, the book, hot off the press, landed in the mailbox of their recently-built apartment in Amsterdam West precisely on the day Leonard and Brigitte got married. It had been Freed’s own idea to make a photo book on Jewish life in Amsterdam – at least what was left of it after the Second World War. Of the 80,000 Jews who had lived in the capital in 1940, after the Shoah there were only 14,000 still alive. When Freed visited Amsterdam for the first time in 1952 as a young Jewish American, he was confronted with the deep wounds and social dislocation of a Europe just emerging from the war. During that first trip to Europe he fell in love with a Dutch girl. He visited her parents’ home, only to discover that the family had been rabid National Socialists during the war. “Can you imagine that?” Freed said. “As a naive Jewish boy from another world I suddenly found myself sitting at table with people that I could not help but find very friendly and likeable, while of course from the Dutch point of view I should have kept my distance from collaborationists like that.” (5) The way that he recounted this distressing experience, with a mixture of empathy and journalistic detachment, was typical of Freed. The ‘light irony’ of which Hofland spoke was not so much dictated by Freed’s character, as the way that life and history presented themselves to him, full of dilemmas, paradoxes and unforeseen outcomes.

Henk Hofland very clearly remembers Freed playing with the idea of doing a photo essay on the Jews of Amsterdam. “I introduced him to my fellow editor at the Algemeen Handelsblad, Max Snijders. He was well informed on this subject. They worked together to do the book.” It must have been an interesting duo, because Snijders (1929-1997) was known as a flamboyant, very self-assured journalist who could talk his way into any situation, while Freed was a man of few words, who preferred to stay in the background. Both were 27, but ambitious in their own way. The publication is proof that there was no lack of synergy when the two came together. While in 1958 there were sensitivities on both the Dutch and Jewish sides about something as explicit as picturing the contemporary Jewish community, Freed and Snijders succeeded in finding a good balance between the shame and guilt of the Dutch and the resignation and reticence of the Jewish community. In his nuanced, almost didactic text Snijders explains how in the thirteen years since the war Jewish life had again taken up its course: “A new community has grown up, less colourful, but hardly less kaleidoscopic.” It was very much the concern of the author and photographer to sketch things as they were at that moment, to paint a picture of a living community. It was explicitly stated that the book was not a catalogue, census or inventory, but was intended to reflect “an aura”. Yet in Joden van Amsterdam Freed could not escape from primarily depicting expressions of colourful orthodox Jewish life although – even back before the war – the Jews in Amsterdam were largely assimilated and secularised. But for a photographer folklore always makes a more interesting picture than a college lecture hall full of students, where there is nothing explicitly Jewish to be seen, while they were perhaps all Jews.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten