Continuing her series on photography books, Liz Jobey applauds a venture to create new editions of out-of-print volumes

Liz Jobey guardian.co.uk, Monday 16 March 2009

Liz Jobey guardian.co.uk, Monday 16 March 2009

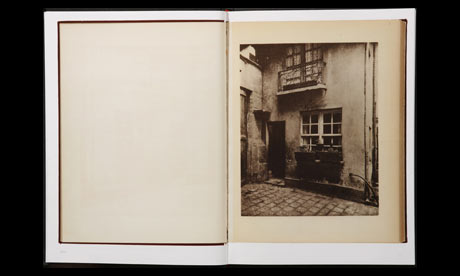

Eugène Atget's Photographe de Paris. Photograph: Errata Editions

Well, here's a good idea: a new series of photography books about photography books. If this sounds a bit like trainspotting, it probably is. But one of the main growth areas in photography over the past decade has been the interest in photographic books – not so much in new titles (though there has been a definite expansion there), but in second-hand books, the ones that are increasingly rare, out of print, and out of the range of most pockets.

Errata Editions, a small American press, has just launched its first four titles, based on the idea – which, as far as I know, has never been tried before – of presenting rare and out-of-print books in their original formats: not as facsimile editions or reprints, but as page-by-page reproductions, scanned from the original, displayed in their original sequences, with their original texts (translated into English where necessary), title pages, colophons and even errata slips.

Each book has a new essay by a contemporary photo historian, a short biography of the photographer, data about the original publication – where it was printed, how many copies, etc – and a list of other titles by the same photographer. In other words, each Errata book acts as a kind of host to its original title.

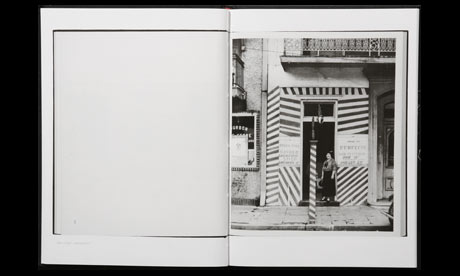

Walker Evans's American Photographs. Photograph: Errata Editions

Walker Evans's American Photographs. Photograph: Errata Editions The first four titles in the series are Eugène Atget: Photographe de Paris – which was the first book of Atget's photographs, published in 1930 three years after his death; Walker Evans's American Photographs, published by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1938; FAIT, the French photographer Sophie Ristelhueber's book of desert landscapes, made after the first Gulf War in 1991 and published in France (and in England as Aftermath) in 1992; and In Flagrante, the British-born photographer Chris Killip's book of pictures taken in the north-east of England at the end of the 1970s and early 1980s, published by Secker & Warburg in 1988.

All four are outstanding works; all are out of print, and the prices of the first editions, despite the financial crisis, are still rising. A quick check on Google reveals the Atget to be available for between $1500 and $2,000 (£1,000-£1,400); In Flagrante, the hardback edition (of which only around 500 copies were distributed), up to $4,000 (£2,800), and American Photographs, published in an original edition of 5,000) around $1,000 (£700). I couldn't even find a copy of FAIT for sale online, only a quote from the photographer and book collector Martin Parr, who said he'd bought six copies when it was published because he knew it was important.

The Errata books are modestly-sized (175mm wide by 240mm high), solidly-constructed hardbacks, bound in black cloth, with the title and series number stamped in white on the front and spine. A wide band of cream art paper folded around the middle of each book shows a photograph of the cover of the original title and forms an elegant variation on the traditional dust jacket. It is obvious that these books, born of the success of other books, have been designed to become collectors' items in their own right.

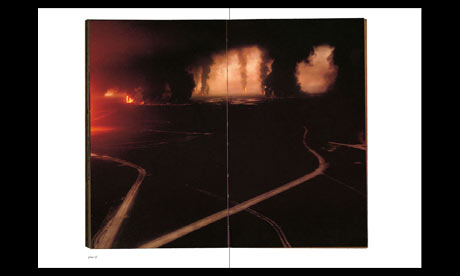

Sophie Ristelhueber's FAIT. Photograph: Errata Editions

Sophie Ristelhueber's FAIT. Photograph: Errata Editions The idea for Books on Books comes from Jeffrey Ladd, who since 2007 has written the widely-respected photoblog 5B4. (I've written about him before, when I was trying to discover the identity of "Mr Whiskets", the pseudonym he chose for his original pieces. Now, though, most people who read him know his real identity.) Ladd is a photographer and a printmaker, and teaches at the International Center of Photography in New York. Books on Books came out of his realisation that, as rare photography books continued to shoot up in value, some of the greatest titles would all but disappear from public view. With his co-founders, Ed Grazda and Valerie Sonnenthal, he decided on the format and, somewhat miraculously, persuaded executors and photographers that re-presenting their original books this way meant they would have a second life without the difficulties, or expense, of reprints and facsimiles. It was also important to Ladd that his series should be affordable and available to students and photo-enthusiasts alike.

One of the surprising things about these new editions is that, although some of the photographs are reproduced at a smaller scale, the way they are presented makes you look at the images differently. I wouldn't go so far as to say that it turns the original pictures into "objects", but they now sit on a page-within-a-page, with the margins, gutter markings and page edges of the original clearly visible around them. Initially there is a sense of dislocation when you look at the pictures, as if you were looking at specimens. But once you get used to the shift , there are times, particularly when the images are reproduced one to a page, when it almost simulates the feeling of looking at the original book.

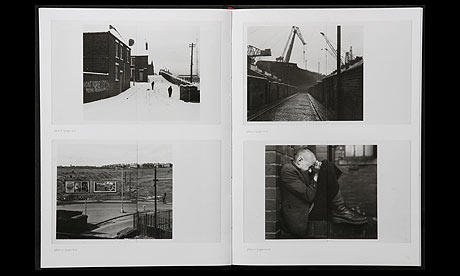

Chris Killip: In Flagrante. Photograph: Errata Editions

Chris Killip: In Flagrante. Photograph: Errata Editions One advantage of the uniform format is that you notice connections between the different titles. Ladd says he chose the first four because they each had links to one other, and this is certainly clear when you move from Atget to Walker Evans and see the similarities of approach and subject matter. Evans first saw Atget's photographs in 1929 in New York and, as John T Hill explains in his essay on Evans, Atget was "perhaps the single most potent influence in shaping Evans's style". This is not to say that Evans copied Atget's photographs, but what he saw in them must have reinforced his own instinct that a clear, direct documentary picture taken from ordinary life could contain a kind of poetry, become a work of art.

All four titles are resonant of their time. Atget as the great photographer of late 19th-century Paris; Evans, the documenter of mid 20th-century America; Ristelhueber, who transformed the photography of war, just as modern warfare itself was changing in the early 1990s, and Chris Killip's experience of living among two small working-class communities on the north east coast as Thatcherism was starting to threaten their already fragile existence. Like Evans's photographs, each of Killip's is a complete statement in itself, with its own emotional, political and aesthetic charge. It was when I saw some of these photographs in Newcastle in 1977 that I realised for the first time how it was possible to look at a photograph as you might at a painting, and find internal rhythms and resonances that reach beyond the basic visual information supplied. I always wondered why In Flagrante was never reprinted. It turns out it was because Killip didn't want it to be. He believed it was a book of its time, and should remain so. Now, though, reproduced in this new format as a work of reference, he has been pleased to see it reappear.

The history of photography has been measured out in books. Books are still where photographers present the most definitive versions of their work. One of the ironies of the past few years has been that when it comes to old books, audiences have been growing as the books have been disappearing. This new venture is a way of redressing the balance.

Eugène Atget: Photographe de Paris; Walker Evans: American Photographs; Sophie Ristelhueber: FAIT and Chris Killip: In Flagrante, from the Books on Books series, published by Errata Editions, £33 each.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten