PARIS, TEXAS / Wim Wenders (Director), Sam Shepard (Writer), Chris Sievernich (Editor)

1984, Berlin, 511 pages, 193 x 240 x 23

by David H. Schleicher

Let’s go for a drive.

…Paris

Texas!

Paris, Texas

Putting the two words together is something of an oxymoron. A comma between them becomes a pregnant pause. Two places couldn’t be further apart than Paris and Texas. We can’t seem to come to terms with its existence as a real place…but then we see a picture of that barren stretch of land. For a man named Travis and his son Hunter it becomes the center of their universe, the origin of all things, a place achingly unreachable, alive only in their dreams where they long to be with a woman named Jane in a faraway land where the purchase of a remote plot of dirt represents the key to a happiness that could never be.

It’s a place that can only exist as an “idea ——- of her…love…family…redemption…the movies.”

As I recently announced on my own ever-expanding list of favorite films, and soon to be registered in the Best Films of the 1980’s polling at Wonders in the Dark, Wim Wender’s 1984 Palme D’Or winning Paris, Texas is hands-down my pick for the greatest film of the decade.

I decided to revisit Paris, Texas, which I only saw for the first time back in 2005. It was one of those weirdly magical movie-watching experiences. I was flipping through the channels on TV and came across it totally unaware of its existence before that moment, not realizing I had missed the first thirty minutes or so…but I was instantly transfixed. By the end of the movie, I was beside myself and re-watched the entire film from the beginning the very next day when it was rerun. Shortly thereafter I purchased the DVD and re-watched it yet again.

Dont give me that look...Ive been waiting for you forever in PARIS TEXAS.

Jane is not a fancy woman…that’s only her in a movie.

Looking back on my original review, I’m surprised I didn’t see fit to mention the following:

Ry Cooder’s unforgettable and blisteringly unique film score that travels across the desert along with Wim’s camera and hits all the right chords. Only Anton Karas’ zither score from The Third Man or Jonny Greenwood’s moody strings from There Will Be Blood could possibly outrank Cooder’s high-water mark for originality in film music composition.

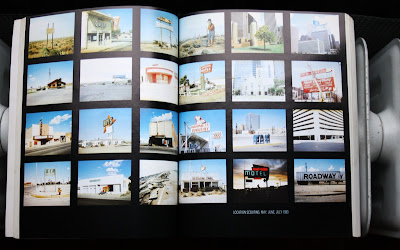

The beautiful photography of the LA hills and valley and the Houston cityscape. One will always be scorched by the photography of the barren desert, but these haunting shots of civilization are equally as powerful.

Some great movie moments when Travis becomes entranced watching the shadow of an airplane move across the ground as it takes off or when he attempts to walk his son home from school after the maid gives him lessons on being a “rich father/poor father”. Both of these scenes are brilliant and simple examples of a director telling his story and revealing something about the characters through what is seen in camera — the classic “show, don’t tell” move.

Hunter’s fascination with “space” revealed in his ramblings about the Big Bang and time travel while on the road with Travis…or his perfectly 80’s LA kidspeak where he’s always on the verge or pre-irony and innocent precociousness and clips phrases by saying things like “I want to come with” instead of “I want to come with you” and “Night” instread of “Good night.”

In my original review I failed to name the writers (a most grievous sin from a fellow writer) — L. M. Kit Carson and Sam Shepard — who were later honored in my post on The Best Screenplays of All Time.

There’s also a pensive and quiet suspense that is only experienced on repeat viewings when you know everything is slowly building up to that moment when Hunter spots Jane for the first time at the bank…and then Travis follows her to that down-and-out Houston neighborhood with the Statue of Liberty mural on the back wall by the dumpsters, and he enters the peep-show where the audience finally meet Kinski’s Jane in person. On first viewing you expect a show when she appears, but on repeat viewings you hold your breath…for all that conversation. “You can just talk…she’ll listen.”

In the years since first seeing it, my love for it has only grown, and any time it is mentioned — oh, how I became tinged with meloncholy when I learned it was rumored to have been Kurt Cobain’s favorite film, and oh, how I laughed the other day when it was referenced in a skit from The State (finally on DVD), and yes, I could probably set the record for x hours straight spent talking about Paris, Texas — I get an immense feeling of satisfaction.

Yes…Paris, Texas…I’ve been there, and it is wonderful. If you’ve never been, you’ll never know…so visit soon and visit often. When you layover in Houston, we’ll be waiting for you at The Meridian…room 1520.

Written by David H. Schleicher

And I would walk 500 miles...just to be in Paris, Texas again.

MOVIE REVIEW

'PARIS, TEXAS' FROM WIM WENDERS

By VINCENT CANBY

Published: October 14, 1984

A most peculiar-looking figure wanders slowly but with purpose across the bleached expanse of a southwestern American wasteland. He wears a dusty, double-breasted suit, shoes so ragged they no longer qualify as footwear, a dirty shirt with a filthy but neatly knotted necktie, plus a maroon baseball cap. He stops, drinks the last of the water from a plastic container and continues his journey. From nowhere to nowhere.

When, eventually, he stumbles into a seedy little trailer camp, he collapses before he can open a soft-drink bottle. The man, who refuses to talk, is more or less threatened back to life by an ominous, German-accented doctor who, going through the man's pockets, finds a Los Angeles telephone number, which he calls.

These constitute the opening scenes in Wim Wenders's initially promising, new ''road'' movie, ''Paris, Texas,'' written by Pulitzer Prize- winning playwright Sam Shepard (''Buried Child''), whose screenplay was adapted by L. M. Kit Carson. The movie, the winner of the grand prize at this year's Cannes Festival, will be shown at 8:30 tonight at Avery Fisher Hall to conclude the 22d New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, and will open here commercially some time in November.

The desert derelict is eventually identified as Travis (Harry Dean Stanton), whose younger brother Walt (Dean Stockwell), a prosperous manufacturer of road signs, flies from Los Angeles to Texas to reclaim the brother who has been missing and presumed dead for four years.

As Travis and Walt begin their long drive back to Los Angeles - Travis sitting silently in the back while Walt drives, ''Paris, Texas'' looks as if it's going to be another classic Shepard tale about sibling relations, explored most effectively in Mr. Shepard's current Off Broadway hit, ''Fool for Love,'' and in his ''True West,'' which recently concluded a long run at the Cherry Lane Theater. Travis and Walt could be first cousins to the brothers in ''True West,'' in which one brother is a foul-mouthed, possibly psychotic thief and the other an uptight, fastidious fellow who aspires to become a screenwriter.

''Paris, Texas'' begins so beautifully and so laconically that when, about three-quarters of the way through, it begins to talk more and say less, the great temptation is to yell at it to shut up. If it were a hitchhiker, you'd stop the car and tell it to get out.

''Paris, Texas'' has the manner of something to which too many people have made contributions. One problem may be that Mr. Shepard is the kind of writer who writes best when he writes fast. No matter how serious he is, he's also funny. His art - and his temperament - do not seem to adjust well to the sort of long, collaborative process by which movies are made. ''Paris, Texas'' seems to be a movie that's been worried to death.

Though Mr. Wenders is fascinated by the American scene, as he has shown in his ''Alice in the Cities,'' ''The American Friend'' and ''Hammett,'' his feeling is as much the result of his knowledge of American movies as of the first-hand experience out of which Mr. Shepard writes. He has a sense of humor, but it's more theoretical than actual.

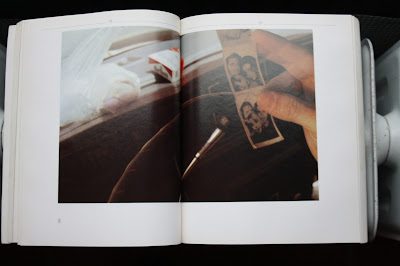

The first half of ''Paris, Texas'' is Shepard at his best, as, gradually, Travis begins to respond to Walt during the drive to California. At one point, Travis shows Walt a snapshot of a scrubby field in Paris, Texas.

Walt: ''How come you got a picture of a vacant lot in Paris, Texas?''

Travis: ''I bought it.''

Walt: ''You bought a picture of a vacant lot?''

Travis: ''I bought the lot.''

Travis, it turns out, believes that he was conceived in Paris, Texas, and he's always had the dream of one day moving there with his wife, Jane, who has been missing almost as long as Travis, and their small son, Hunter, who has been living with Walt and his wife, Anne, since his parents disappeared.

What has Travis been doing during these last four years, and where is Jane? I've no doubt that, left to his own devices, Mr. Shepard would have come up with a resolution to these mysteries that would have provided a far more satisfactory payoff than the one arrived at by the playwright working in collaboration with the director and Mr. Carson. Mr. Shepard's method is to distill from ordinary experiences and feelings a reality that is so dense it appears to be surreal.

This is exactly the quality that illuminates the first half of ''Paris, Texas,'' when Travis, back in the middle-class environment of Los Angeles, attempts to establish some sort of connections with Hunter, played with enormous, comic self-assurance by Mr. Carson's seven-year-old son, also named Hunter.

Life in the small Los Angeles house is not easy for any of them. Anne (Aurore Clement) is afraid that if Travis takes the boy away, it will somehow threaten her marriage to Walt. Walt is torn by his affection for his older brother, for the boy and for his wife. The boy can't reconcile having a foster father he adores and a real father he doesn't know and whose shabby appearance is - well - embarrassing to him in front of his friends.

Travis is at loose ends. He can't sleep and, on his first night back, he spends the entire night shining every pair of shoes in the house.

The film is wonderful and funny and full of real emotion as it details the means by which Travis and the boy become reconciled. Then it goes flying out the car window when father and son decide to take off for Texas in search of Jane (Nastassja Kinski), Hunter's long-lost mother. Everything suddenly becomes both too explicit and too symbolic. It's not giving anything away to reveal that what the movie - rather tardily - seems to be all about is the difficulty in communication between men and women, nor that the sequences in which this is demonstrated are awful.

Mr. Stanton, who can be seen currently in the riotous ''Repo Man'' and will be remembered for, among other things, his performance in John Huston's ''Wild Blood,'' is a marvelous Shepard character. Every foolish endeavor in American history appears to be written in the deep lines and hollows of his face. There is a gentleness about him that at any moment may erupt in inexpicable violence.

Mr. Stockwell, the former child star, has aged very well, becoming an exceptionally interesting, mature actor. Miss Clement, whose French accent is a bit thick for someone who is supposed to have been living in California for a few years, is also moving as Walt's baffled wife. Miss Kinski, however, is memorably miscast. The more she tries to act, the worse her performance becomes, which is more than unfortunate, considering the importance of her scenes to the end of the film.

Prominent in the supporting cast are Bernhard Wicki, the German director who appears as the menacing doctor early in the movie, and John Lurie, one of the stars of ''Stranger Than Paradise,'' who does a tiny walk-on here for Mr. Wenders, who was one of the earliest supporters of that Jim Jarmusch film.

As photographed by Mr. Wenders's long-time associate, Robby Muller, ''Paris, Texas,'' a French-German co-production made in this country, looks great. However, the film, at best, is extremely diluted Sam Shepard.

The Cast PARIS, TEXAS, directed by Wim Wenders; written by Sam Shepard; adaptation by L. M. Kit Carson; photography by Robby M"uller; edited by Peter Przygodda; music by Ry Cooder; produced by Don Guest. At Avery Fisher Hall, as part of the 22d New York Film Festival. Running time: 145 minutes. This film has no rating. Travis Harry Dean Stanton Jane Nastassja Kinski Walt Dean Stockwell Anne Aurore Clement Hunter Hunter Carson Doctor Ulmer Bernhard Wicki Carmelita Socorro Valdez Crying Man Tom Farrell Slater John Lurie Stretch Jeni Vici Nurse Bibbs Sally Norvell Rehearsing Band The Mydolls

Geïmproviseerd meesterwerk Paris, Texas

door Marcel van den Haak6 januari 2007

Een man in pak loopt door de woestijn. Het pak is verfomfaaid, de man draagt een baard van een paar weken en heeft een petje op tegen de zon. Dit is de openingsscène van Paris, Texas (1984) en dit is ook het eerste idee waarmee regisseur Wim Wenders en scenarioschrijver Sam Shepard in de zomer van 1982 aan het verhaal begonnen. Een man die door de Mojave-woestijn dwaalt zonder dat duidelijk is waar hij vandaan komt of waar hij naar toe gaat.

Wenders en Shepard konden die zomer nog niet bevroeden dat ze twee jaar later een meesterwerk zouden afleveren waarmee ze een Gouden Palm zouden winnen. Het verhaal kwam met horten en stoten tot stand, zo blijkt uit Wenders' audiocommentaar op de dvd, en ze hadden nog geen idee waar ze zouden eindigen toen ze al met filmen waren begonnen. Een riskante onderneming dus, waar geen Hollywoodstudio zich ooit aan zou wagen. Maar Paris, Texas is een Duits-Franse coproductie, en in Europa had Wenders met onder meer Der Amerikanische Freund en Im Lauf der Zeit al genoeg krediet opgebouwd om het vertrouwen van de producenten te winnen.

Onvoorstelbaar

Het is onvoorstelbaar dat Paris, Texas onder deze omstandigheden toch zo goed heeft uitgepakt. Toen de eerste helft van de film gedraaid werd, wist geen van de betrokkenen waarom de man (gespeeld door de vooral van bijrollen bekende acteur Harry Dean Stanton) door die woestijn liep en zweeg in alle talen. Waarom zijn broer (Dean Stockwell) al vier jaar taal noch teken van hem en zijn vrouw vernomen had en waarom hun zoontje bij die broer was achtergelaten. Dat is lastig om te acteren, maar de scènes met de twee broers die elkaar na al die jaren weerzien worden er niet minder om. Alleen achteraf, met de kennis over het vreemde productieproces, zie je dat de acteurs eigenlijk nog geen idee hadden waar ze mee bezig waren.

Het is onvoorstelbaar dat Paris, Texas onder deze omstandigheden toch zo goed heeft uitgepakt. Toen de eerste helft van de film gedraaid werd, wist geen van de betrokkenen waarom de man (gespeeld door de vooral van bijrollen bekende acteur Harry Dean Stanton) door die woestijn liep en zweeg in alle talen. Waarom zijn broer (Dean Stockwell) al vier jaar taal noch teken van hem en zijn vrouw vernomen had en waarom hun zoontje bij die broer was achtergelaten. Dat is lastig om te acteren, maar de scènes met de twee broers die elkaar na al die jaren weerzien worden er niet minder om. Alleen achteraf, met de kennis over het vreemde productieproces, zie je dat de acteurs eigenlijk nog geen idee hadden waar ze mee bezig waren.

Toen de scènes in de woestijn en in Los Angeles – waar de man zijn inmiddels bijna achtjarige zoontje (Hunter Carson) terugziet en er een langzame toenadering tussen hen ontstaat – gedraaid waren, was het einde van het script bereikt. Schrijver Shepard was inmiddels met een andere film bezig (als regisseur), waarop Wenders besloot in zijn eentje het vervolg te schrijven. De cast en crew kregen twee weken vrij. Vanaf dat moment had het finaal mis kunnen gaan. Er was een verzameling prachtige scènes, niet in het minst door het felgekleurde camerawerk van Robby Müller en de lome gitaarmuziek van Ry Cooder, maar met een afgeraffeld tweede deel heb je natuurlijk geen goede film.

Vader-zoonfilm

Na een kunstgreep – vrouw van broer weet meer, maar had het nooit iemand verteld – kan Stanton gericht op zoek gaan naar zijn vrouw, en hij neemt zoonlief mee. Op basis van het ruwe script van Wenders improviseren de twee er in de auto op los, met veel verhalen van het joch over astronomie. Ook hier zakt de film wonderwel niet in. Van een film over de relatie tussen twee broers is het een vader-zoonfilm geworden, en een heel goede. Subtiel, zonder al te veel sentiment. Begeleid door imponerende beelden van een spaghetti aan wegen en viaducten, die de desolate woestijn uit het begin van de film hebben vervangen.

Na een kunstgreep – vrouw van broer weet meer, maar had het nooit iemand verteld – kan Stanton gericht op zoek gaan naar zijn vrouw, en hij neemt zoonlief mee. Op basis van het ruwe script van Wenders improviseren de twee er in de auto op los, met veel verhalen van het joch over astronomie. Ook hier zakt de film wonderwel niet in. Van een film over de relatie tussen twee broers is het een vader-zoonfilm geworden, en een heel goede. Subtiel, zonder al te veel sentiment. Begeleid door imponerende beelden van een spaghetti aan wegen en viaducten, die de desolate woestijn uit het begin van de film hebben vervangen.

Shepard was op tijd terug om het laatste deel van Wenders' schetsen, dat zich afspeelt in Houston, in sneltreinvaart nader uit te werken. De acteurs (Stanton en Nastassja Kinski, die zijn teruggevonden vrouw speelt) kregen vervolgens drie dagen de tijd om de nieuwe tekst uit hun hoofd te leren. Deze haastklus mondt uit in een van de hoogtepunten uit de filmgeschiedenis, waarvan ik inhoudelijk niets zal prijsgeven. Maar een twintig minuten durende dialoog in een op z'n zachtst gezegd ongewone omgeving, met langdurige close-ups van de luisterende in plaats van de sprekende partij, en een onafgebroken emotioneel shot van acht minuten, dat is simpelweg filmmaken op zijn best. "Als ik de film nu gemaakt zou hebben, zou ik veel vaker gesneden hebben," zegt Wenders twintig jaar later, "mensen zijn zo snel verveeld tegenwoordig." Godzijdank dateert deze film uit 1984 en kunnen we er nu nog, op dvd, van genieten.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten