Southern Gothic

William Eggleston is even more colorful than his groundbreaking photographs.

|

‘Bill Eggleston has a show at the Whitney?” asks a woman at the bar of the Lamplighter Lounge in Memphis. She practically spits out her Budweiser. “I hate his shit!” Sam Cooke is on the jukebox, which plays real 45s; place mats are spread along the wood veneer, and the complimentary matchbooks are from D&D Bail Bonds in Wichita Falls, Texas. The bartender, Shirley, slices potatoes in the kitchen. A young couple are making out at a back table.

“I’m from in the same town as him,” says another woman, who hails from Sumner, Mississippi. “I know his cousin Maudie. She’s a photographer, too.”

“I like Weegee’s photographs,” the first woman cuts in. And again: “Bill Eggleston at the Whitney?”

There’s a snapshot of William Eggleston at the back of the Lamp, displayed by a vase of unnaturally colored silk flowers, a dish of peppermints, and a cutout of James Dean. If this sounds like an Eggleston photograph, it’s close. That same day, in fact, the Lamp turns up in a box of proofs at the Eggleston Artistic Trust. There in supersaturated color is the EAT MORE POSSUM sign.

Eggleston has a precarious relationship with the Lamp, one of his favorite haunts. In fact, he’s barred from entering. “I got really drunk one time,” he admits, “and I threw a hamburger at Shirley, who had just made it. But we’re still friends.”

Shirley concurs. “He calls me up every now and then, asks how I’m doing, and I say, ‘Good,’” she says, fond but firm. She is pleased to own an Eggleston photograph at home and proud of his success, but, like the Lamp’s regulars, her feelings for her famous neighbor are complicated. “I like Bill, but he can’t come in here. Will you be sure and tell him I said hello?”

The consummate insider-outsider, Eggleston remains aloof in the many worlds he inhabits—including the art circles of New York and the dive-bar culture of Memphis. Those intricate relationships will be on full display at the Whitney when his first comprehensive retrospective, “William Eggleston: Democratic Camera,” opens Friday—his most prominent return to the city since his MoMA debut in 1976.

We met recently at the offices of his archive, a few miles east of the Lamp. As always, he’s dressed sharp: off-white lace-up oxfords, dark tailored pants, an undone bow tie over a blue oxford shirt monogrammed with a large orange B. “Got it at a yard sale. It had my name on it: B, for Bill.” He laughs. Eggleston has been known to wear the occasional knee-high Austrian riding boots and, according to Lamp regulars, “Zorro capes.” “Sometimes, yes,” he says. “It’s comfortable, and it looks good.”

In 1967, when Eggleston arrived in New York from Memphis bearing a box of slides that would redefine photography, he was an anomaly. Not only was he one of the first photographers to wholeheartedly embrace color, but he embraced exactly what made color photography so controversial in highbrow circles: He treated the commonplace as art. Eggleston shot “democratically,” meaning anything—parking lots, shopping centers—was a worthy subject. “I thought I was doing the right thing, put it that way,” he says now. “And if someone told me something otherwise, I just put it aside.”

He was soon befriended by a small “club” of artists—equally groundbreaking photographers Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand. “Though our work was different, we felt that we were compatriots,” Eggleston says. “Somehow I knew we were, attitude-wise, doing the same thing.”

Eggleston’s 1976 MoMA show launched his career and proved a turning point in the history of photography. Scorned at the time for being vulgar and banal, the show has since been revered for exactly those reasons. The exhibit was accompanied by a cheekily titled book, William Eggleston’s Guide, misread by many as an artistic travelogue to his native South. In truth, it was a Michelin guide to Eggleston’s singularly heightened way of seeing: His use of supernatural dye-transfer color, which implied that the ordinary was not at all so. His startling compositions directed viewers to look as closely as his camera, to recognize the grace, violence, and humor implicit in the mundane. A dog walking down a street. A fire burning in a barbecue grill. A red ceiling.

The New York art world became fascinated with Eggleston’s southernness, and he, in turn, immersed himself in the scene, setting up house in the Chelsea Hotel with Warhol star Viva. But he never really became a New Yorker. Eggleston maintained a life in Memphis and a marriage to his wife, Rosa (with whom he has three children), while openly having other relationships.

Evidence of this double life shows up in the Whitney retrospective, which highlights the museum premiere of Eggleston’s foray into filmmaking. Stranded in Canton is a full-length video vérité, shot in New Orleans and Memphis and navigating a seventies Delta netherworld of quaalude-popping dentists, soliloquizing transvestites, cryptologists, geeks, bluesmen—a southern equivalent of the Chelsea. His parallel lives, he says, are necessary: “It does get confusing sometimes. But each of these things allows the other. It creates a state of mind.”

|

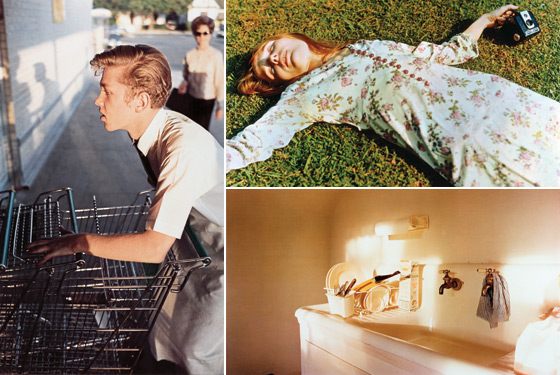

Untitled, from "Los Alamos," 1965-68 and 1972-74; Untitled, 1975; Untitled (St. Simons Island, Georgia) from "Morals of Vision," 1978. © Eggleston Artistic Trust) |

During his time in New York, Eggleston would roam the city with cameras, but he rarely shot pictures. “Those streets were Garry Winogrand’s world,” he says. Since then, his style of working has loosened so that he never knows where he will end up each day. A few years ago, he returned to New York and photographed a crushed-car lot in Queens. Recently he completed a Fondation Cartier commission to photograph Paris. “Years ago there, working in black and white, heavily under the influence of Henri Cartier-Bresson, I just didn’t see any pictures,” he says. “Now, once I start working, it’s no different from anywhere else in the world. Sometimes I have to ask, ‘Are we in Paris?’ ”

The Whitney retrospective certainly demonstrates Eggleston’s mastery in depicting the place of a place. But it is equally possible to see the show as just the opposite: a career-long meditation on how the particular can reveal the abstract—the composition of light and its reflection.

It’s four o’clock, and Eggleston, sitting on the stoop outside his office, smokes another in a long line of cigarettes. The late sun striking the cars in the lot recalls his first real color photograph: a bag boy pushing a row of carts. “This is beginning to be my favorite kind of light,” he remarks, his words precise but elegantly drawn out. “It brings out a spectrum that appeals to me, warmer colors that I don’t always notice at other times. It’s like when a thunderstorm moves through and the light changes swiftly from cold to warm.”

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten