Elias Canetti, The Voices of Marrakesh

Elias Cannetti’s narrative set in Marrakech during the mid 1950s describes a city still under the shadow of French colonial presence. The dates of publication of the original German edition (1967) and English translation (1978, 1982) may give the impression that the text deals with a post-colonial moment. However, a close reading of the text reveals the continuing presence of French colonial structure dominating the vast desolate landscape of houses which the French called native quarters. Canetti’s narrator presents vivid images of poverty, desperation, and loss akin to those portrayed by George Orwell in his 1939 essay, “Marrakech”. Moving through the narrow alleys of the city, the seat of bygone powerful imperial dynasties, once the center of prosperous trans-Saharan trade and home of the best craftsmen, Canetti’s narrator observes a world both shocking and fascinating by its contrasts.

There are markets for camels and donkeys just outside the Bab-el-Kemis. The fact that the camels are brought from the southern provinces of the country to sell to the butchers in Marrakech seems hard to accept, and creates a strong feeling of disillusionment for the narrator who it appears has never seen camels in real life. Being based at a luxurious hotel in the French part of the city, the narrator’s exploration of the native quarters follows the same pattern of shock and repulsion. The objects of his gaze vary from one day to another. There are, for instance, blind men chanting the name of Allah in an unchanging rhythmical pattern, there is also a blind beggar who will put a coin in his mouth and chew it for a long while. This is his way for identifying the value of the coin and also for bestowing his blessing on the benefactor. There is also the woman at the grill suffering from a mental problem whom the narrator takes for a captive and stands to observe under the disapproving eyes of passers-by. Not far from the ruined house where the insane woman lives lies the Koubba visited by scores of pilgrims. The wooden door of the Koubba has a knob in the shape of a ring from which dangle rags. These “were supposed to be shreds of the saint’s own robe and for the faithful there was something of his holiness in them.” (38)

The core of Canetti’s narrative, however, revolves around the Mellah, a bustling place densely populated by Jewish families. The narrator’s initial foray inside the Mellah makes him aware of the rampant poverty which envelops the whole quarter. Jewish shops are ‘little low booths” and the wares sold are extremely picturesque. What strikes the narrator most is the discreet attitude of Jewish traders:

They had a way of swiftly glancing up and forming an opinion of the person going past. Not once did I pass unnoticed. When I stopped they would scent a purchaser and examine me accordingly. But mostly I caught the swift, intelligent look before I stopped. (40)

Moving deeper into the Jewish quarter past the bazaars, the narrator comes into a square whose charm and ambiance seem to charm and compel him to return on several occasions:

I had the feeling that I was really somewhere else now,that I had reached the goal of my journey I did not want to leave, I had been here hundred s of years ago but I had forgotten and now it was all coming back to me. I found exhibited the same density and warmth of life as i had in myself. I was the square as I stood in it. I believe I am it always. (45)

This initial visit is a sort of homecoming. Being a Jew himself, the narrator feels deep attachment to the Mellah. While his promenade in the Jewish cemetery is marred by the persistent and clamorous pursuit of beggars, his life in the Jewish quarter and its dwellers drives him to return the next day and make the accidental acquaintance of the Dahane family. The narrator’s decision to enter the Dahans’ house, however, brings more nuisance that indeed appease his curiosity. Over the remaining period of his stay in Marrakesh, the narrator is pestered with the incessant requests of Elie Dahane, a young unemployed member of the family, tofind him a job. When his requests have been politely turned down, Elie Dahane insists that a letter of reference should be written on his behalf recommending his skills and character to the Commandant of the American camp in Ben Guerir. Nothing but full compliance with his demand could make an end to Elie Dahane’s unadvertised visits to the hotel. The power he seems to attach to the letter is at once incontestable and incomprehensible.

The last sections of the narrative focus on French colonial presence in the city and present strange tales of sexual fantasies told the narrator by the owners of a French restaurant and A French bar which he frequents.

De kracht van overlevers

Vrijdag 4 juli 1997 door Anneriek de Jong

'Op reis', schrijft Elias Canetti in Stemmen van Marrakesch, 'neemt men alles zoals het valt, de verontwaardiging blijft thuis. Je kijkt, je luistert, je bent verrukt over de meest afschuwelijke dingen omdat ze nieuw voor je zijn. Goede reizigers hebben geen gevoel.'Canetti, die in 1954 voor een maand of wat in Zuid-Marokko neerstrijkt, is inderdaad dikwijls verrukt wanneer hij door de soeks en de medina en de geurige straten van Marrakesch zwerft. En alleen al deze toestand botst met zijn opmerking over de gevoelloosheid van de ware reiziger. Als er ìemand emotioneel is, dan is hij het, de heer uit Europa die expres geen Arabisch of Berbers heeft geleerd, omdat hij door de puurheid van de klanken geraakt wil worden. Ja, deze vreemdeling zet zijn gemoed wagenwijd open. Ontvankelijk toont hij zich niet alleen voor de hem omringende schoonheid, maar ook voor de energie die het leven in Marrakesch uitstraalt.

Zelfs in de nederigste wezens ontwaart hij een onverzettelijke kracht. Een golf van blijdschap stroomt door hem heen bij het zien van een magere ezel met een enorme erectie: die is 'sterker dan de stok waar men hem de nacht daarvoor mee had gedreigd.' En trots is de schrijver op een armzalig bundeltje mens aan zijn voeten: 'Misschien had het geen armen om naar de muntstukken te tasten. Misschien had het geen tong om de 'l' van Allah te vormen en werd de naam van God bij hem ingekort tot 'a-a-a-a-a-'. Maar het leefde en met een weergaloze ijver en volharding stootte het zijn enige klank uit, uren en uren achtereen, totdat het op het hele wijdse plein de enige klank geworden was, de klank die alle andere klanken overleefde.'In de mellah, de oude jodenwijk, heerst nog meer armoe dan elders, maar ook daar registreert Canetti vooral de rijkdom: het montere geklop en gehamer van de ambachtslieden, het genot waarmee een sloeber een karbonaadje verorbert, de met flair gevoerde discussie tussen een stel oude mannen. Opeens weet Canetti: dit pleintje in het hart van de mellah is het doel van zijn reis. 'Ik wilde hier niet meer vandaan; honderden jaren eerder was ik hier al geweest, maar ik was het vergeten en nu herinnerde ik het me allemaal weer.'

Roept de mellah van Marrakesch zijn vroege kindertijd in hem wakker? Ruschuk, of Roese, aan de benedenloop van de Donau in Bulgarije moet begin deze eeuw een kleurrijk stadje geweest zijn, wild, bijna oriëntaals. In zijn autobiografie Die gerettete Zunge beschrijft Canetti (1905-1994) hoe hij als kleine jongen uit de jodenwijk van Ruschuk gefascineerd en angstig door al het vreemde aangetrokken werd: door de vele talen die hij op straat hoorde spreken, door de hem onbekende gewoontes, van de Turken bijvoorbeeld in de aangrenzende wijk, door de woeste schoonheid van de langsreizende zigeuners van wie gezegd werd dat ze joodse kindertjes stalen.

Het jodenkind Elias leerde al snel om altijd op z'n hoede te zijn, en die oplettendheid herkent hij in de mellahbewoners. 'Geen enkele keer bleef ik onopgemerkt wanneer ik langsliep; (...) meestal trof hun snelle en intelligente blik mij lang voordat ik stil was blijven staan.' Maar het is meer dan de intelligentie, de kracht en de alertheid van de joodse overlevers, van àlle overlevers, die hem in Marrakesch zo frappeert. 'Ik vond er', formuleert hij ietwat plechtig in de toch al omzichtige vertaling van Theo Duquesnoy, 'die dichtheid en warmte van het leven uitgestald die ik in mijzelf voel.'

En zo is het precies: Stemmen van Marrakesch is, gelukkig, een uiterst persoonlijke reeks observaties, scherp, poëtisch en even warm als de Marokkaanse zon waarover Canetti nooit klaagt.

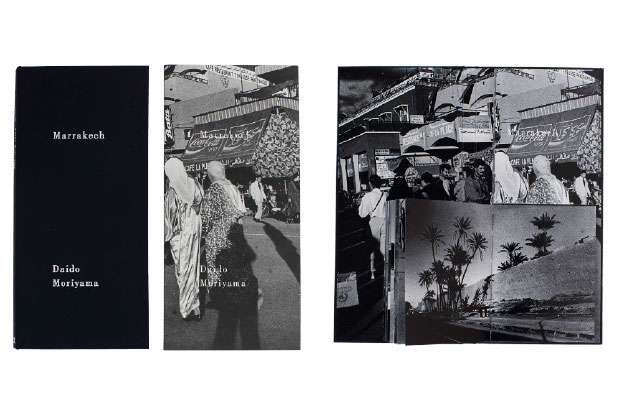

Daido Moriyama, Marrakech SUPER LABO / Kamakura, Japan, 2014 / Designed by Koichi Hara / superlabo.com

Marrakech injects a shot of energy into a body of work Daido Moriyama made decades ago when he visited Morocco. This long, narrow book comes enclosed in a slipcase and opens to reveal two book blocks stacked on top of each other. The reader is invited to mix-and-match the full-bleed, high-contrast, black-and-white images according to his or her whims—an experiment in what Todd Hido calls “exquisite-corpse-style” sequencing. Lesley Martin points out, “This approach is very much in keeping with Moriyama’s own practice of revisiting and ‘remixing’ his own work, with less emphasis on the single image than on the visceral experience of viewing a series or combination of images. The inclusion of the viewer in this is another recent strategy of Moriyama’s, so all the more appropriate as a way of organizing the book.”

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten