Erotos.

Tokyo: Libro Port Publishing, 1993. First Edition. Quarto. Black and white images with many closeups of food, body parts, plants, etc.

The erotic and the everyday

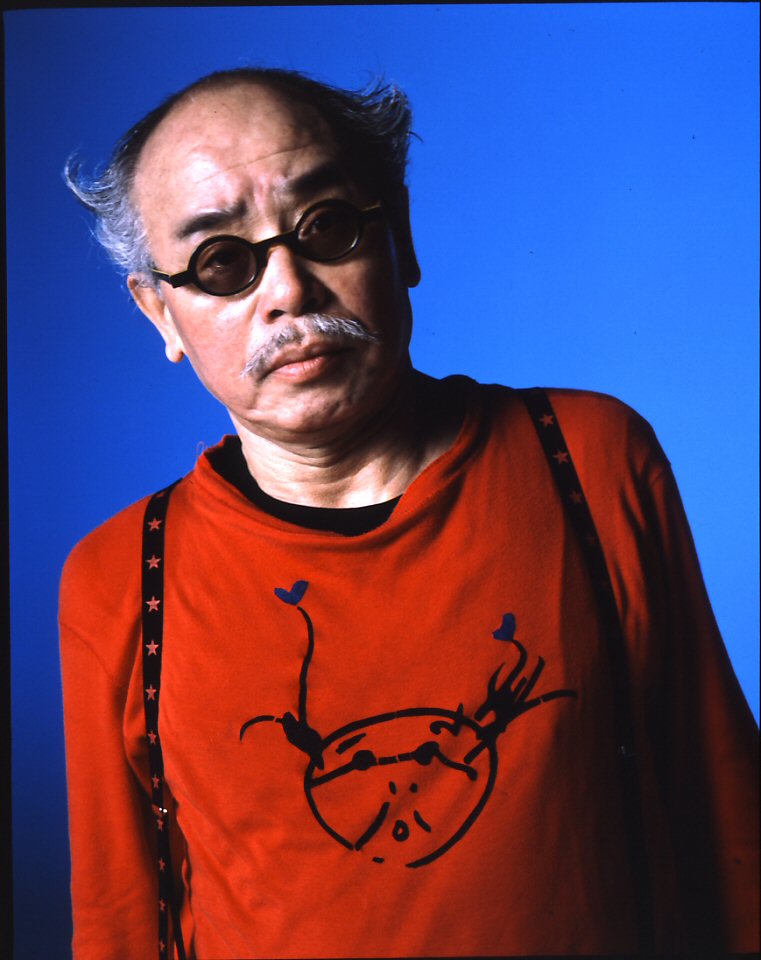

His images of bound women may be shocking, but Nobuyoshi Araki's work is full of life, says Adrian Searle

The first comprehensive British exhibition of Araki's work, now running at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, has generated predictable tabloid shock. The local press have dubbed the 61-year-old Japanese artist "Wacky Araki", and fulminated against the display of his images in a gallery that advertises itself as "family friendly". Araki has also been through the mill of censorship in Japan, where shows have been closed by the authorities. Even though the Ikon's exhibition is an official event in the Japan 2001 festival, and has the support of the Japan Foundation, some doubt whether all his work will make it back to his homeland without being seized at the border.

The disquiet Araki provokes stems from his preoccupation with sexual imagery, in which the invariable focus is on the female body. In Araki's work women expose themselves in the street, lounge about on beds, pose like life models and porn stars, or go about their day naked. In his photographs they are often presented in extreme, elaborate and ritualistic forms of physical bondage: they are tied to bedposts, or bound up in cars; they dangle, fully made-up and dressed in kimonos, from complicated arrangements of ropes.

The whole of Araki's work can itself be seen as a knot of intentions and desires. His models' complicity, their willing subjugation, is never in any doubt; but that, somehow, isn't entirely the point. Maybe the tabloids are right. Araki's work is as shocking as it is full of life. In the end, you have to take Araki's work as a whole - and there is a very great deal more to it than the sex - or not at all. You can't sieve out the apparently unconscionable and hope to be left with anything other than a sanitised half-truth. You can't, in other words, keep the artist's portraits and flowers, but get rid of the old man with the rope tricks, the camera and the girls.

Araki sees his models as partners, believing that his photographs somehow collapse the distance between his subjects and himself. As for the bondage, it is pure theatre, and something of an art form in the way it manipulates and presents the body. Unlike, for example, the bondage in some of surrealist Hans Bellmer's work, or the gruelling sadomasochistic images in Robert Mapplethorpe's work, Araki's photos never show us female flesh as trussed meat. Araki has said that it was never a matter of tying girls up: "What I was aiming at was the female heart. That's what I wanted to put in shackles. As time went on, the models, so to say, tied themselves up, bound themselves to me."

"I am a genius," he has said, and "I am the photograph." Araki's hunger as a photographer, the fact that he is driven by a desire to consume the world with his camera - and to produce hundreds of publications, thousands of images - cannot be anything other than a kind of mania. In certain works - the long sequence Tokyo Nostalgy, for example - hundreds of images are abutted, unframed, spreading their way across adjacent walls. They are a world entire. They devour you. Almost more like a movie than a sequence of photos, they let you lose yourself in the flow of images. But the oddest sensation - as your eye is jolted by an image of a snail crawling over the tip of a penis, or a cloud in an empty sky - is that it is you who are flowing through this world of static moments.

Araki, it appears, lives through the medium of photography. When his wife, Yoko, died in 1990, he published Sentimental Journey, a series of intimate photographs memorialising their relationship: Yoko in bed, smoking; Yoko dancing; Yoko's hand, emerging from under her hospital sheet, holding Araki's; Yoko dead in her open coffin, up to her neck in flowers; Yoko's shrine, in Araki's home; Yoko's grave.

These photographs have migrated into later series of works. The images keep turning up, like memories - no, not "like" memories, but as memories. Yoko permeates Araki's life and his art.

"Maybe I only had a relationship with her as a photographer, not as a partner," Araki has said. "If I hadn't documented her death, both the description of my state of mind and my declaration of love would have been incomplete. I found consolation in unmasking lust and loss, by staging a bitter confrontation between symbols. After Yoko's death, I didn't want to photograph anything but life - honestly. Yet every time I pressed the button, I ended up close to death, because to photograph is to stop time." He went on: "I want to tell you something, listen closely: photography is murder." His models, he continued, come to him demanding to be murdered. "Women always go home 'happy' after I take their pictures. I truss them up or shave them. Ha ha ha. Then I get love letters, saying, 'It was a happy day for me'."

The children in Araki's photographs from the 1960s are oblivious, like children everywhere, to anything other than the present, as they play and lounge about on the Tokyo streets. And then there are the Tokyo streets, with their flowers and their toy-shop Godzillas and dinosaurs - and somewhere among all this an encounter with death. Even Araki's flowers might be seen as a tribute to the dead, in as much as they are saucy, gorgeous, sexual and full of life - but then the artist has remarked that he finds erotic overtones in the moment when the flowers are wilting. Araki's "Erotos" images of details on a larger scale - an eye, an oyster, a piece of thread on the tongue, cutlery smeared with oil - seem to me to be hymns to the eroticised everyday. The world glistens. You eat the images with your eyes.

Everything is full of life in Araki's world - even the inanimate. The bowls of food in a restaurant, street furniture and leaves, houses, bare branches, old bells, patios after rain, the empty sky. This is a life lived inside the camera, the camera of his imagination, Tokyo's camera.

Germano Celant has called Araki's photos "mosaics of erotic solitude". A beautiful phrase. For Araki, Eros is everything, an erotic tinged with words we find difficult, the taboo words "sentimental" and "nostalgia". A woman suspended from ropes, balanced in space, her body opened to the sights of the camera in a theatrical demonstration of inescapable availability, turned into a doll or a sculpture - she is stilled before the camera, even before she is stilled again by the photograph itself. If she is a metaphor - and she has been seen as a metaphor for the rigid codes of conduct that govern Japanese society - she might be emblematic of that peculiar hovering suspension that occurs in photography, a suspension that is also a distance between moments, between desire and the act, between life and death. But, of course, she is a woman, and Araki is a man.

· Nobuyoshi Araki: Tokyo Still Life is at the Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, until July 8. Details: 0121-248 0708. A version of this text appears in the catalogue to the exhibition.

If Araki Nobuyoshi likes you, he will take you to the cramped bar he owns in the Kabukicho red-light district of Tokyo

This is the nighttime lair of perhaps the planet’s most prolific photographer of the female form, a man dubbed a misogynist, a porn-and-bondage-merchant and a genius, so you expect the outré and Araki doesn’t disappoint. The bar is wallpapered with Polaroid snaps of women: young, older, ripened by years in the water trade, some pigeon-toed and shy; others spread-eagled or violently hogtied, thrust up like Sunday roasts and skewered by his camera.

The middle-aged mama-san Araki employs to serve drinks flits about in a classy kimono, oblivious.

A visitors’ board records the celebrities who have come to pay homage. Bjork, who commissioned Araki to photograph her 1997 album cover Telegram, is there along with controversial Kids-director Larry Clark. “Thank you 4 a lovely day. U R a dirrrty devil,” says one of the more printable comments. The master himself dominates the room with the jittery, uncoordinated energy of a teenager, cackling at his own dirty jokes.

“Be careful of walking around and banging into things with that big cock of yours!” he shouts, as I stumble in the cramped space. Earlier he had told my bemused female companion some of his photographic techniques. “I sometimes blow into the breasts of women while I’m photographing them, to make them look bigger,” he says before exploding in laughter.

Araki Nobuyoshi

But visiting this bar is to merely sip stale water at the grand banquet of Araki’s work, which includes thousands of exhibitions and 350 books, an output he adds to at the staggering rate of 10 every year. His photos are always on display somewhere: a new collection runs at the Barbican in London Belgium

Perhaps his greatest work of art, however, is the iconic tuft-haired Araki himself, a man so famous in Tokyo

Not surprisingly, perhaps, Araki hates most modern photography. “When I look at photos I see no eros or passion. It doesn’t matter if it is a picture of a city landscape, or a woman or Mt. Fuji

Araki can sometimes be spotted at night, walking around Shinjuku and talking to well-wishers. Tokyo

From the collection at the Barbican in London

He has photographed other places, and even men, but it is Tokyo

Although often asked about his next projects, he never plans what he will shoot from one day to the next, and lives in the expectation of chance encounters. “I’m happy in the moment, when I meet someone new and I think we might hit it off. I know nothing about long-term happiness, only what I’m doing right now.” The sexual chemistry of those encounters is what makes a great photo, he believes. “You cannot put into words why you take photos, or what you’re doing when you’re taking them.”

Those libidinous instincts – calling it a philosophy might be pushing it – once made him one of the more shocking and transgressive photographers alive, though the days when a spread-eagled female body could bring the police calling are gone. Many of his photos are scattered around the Internet, along with much worse. Araki claims he never goes online. “I don’t even have a mobile phone.” His motivation, in any case, was never to challenge social or cultural rules, he explains. “I have no interest in changing society, though I might have changed two or three women in my time. I guess I’m stingy; I just don’t want to waste my time on other people. But if somebody says not to do something, it makes you want to do it all the more, right?”

Araki’s work, though, still unsettles, paradoxically – for a man who puts such store in the human warmth between photographer and model – because of the merciless, cold stare of his lens. Nothing is beyond the viewfinder’s unflinching gaze. He famously photographed his entire life with beloved wife Yoko, leaving little out: from their honeymoon and lovemaking to her struggle with cancer, and her cremated bones on a steel gurney.

From the collection at the Barbican in London

The best of his work goes well beyond female objectification and has a pathos that may help it outlive the pornographer tag, such as when Japanese poet Miyata Minori displays the surgery scars from the cancer that will eventually kill her.

Miyata Minori

His latest collection (“6X7 Hangeki”) includes its fair share of pliant, demure young things, but many of the older women stare back at the camera with a mixture of defiance, anger, openness, perhaps affection for the cherubic little man at the other end of the lens. As Guardian critic Adrian Searle recently put it, for Araki, faces are the real private parts.

“I’m trying to catch the soul of the person I’m shooting. The soul is everything. That’s why all women are beautiful to me, no matter what they look like or how their bodies have aged.” Bjork was one of his most memorable shoots. “Half virgin, half old bag, like a shaman…what a face,” he remembers.

Araki’s Bjork

For a man whose libido is so firmly bound up with his art, Araki is surprisingly unfazed by the prospect of decrepitude. He has no fear of getting bored of the camera or being unable to work. “Taking pictures is as natural as eating and then taking a dump for me. It has nothing to do with age. I never think about it, and I’m very diarrheic,” he cackles, then hits again on my female companion. “Be my wife for a day,” he pleads. “Let’s ditch this joint.”

His work is included in “Seduced: Art and Sex from Antiquity to Now,” which runs at the Barbican Art Gallery Londonfrom 12 October 2007 - 27 January 2008 .

David McNeill writes regularly for a number of publications including the Irish Times and the Chronicle of Higher Education. He is a Japan London

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten