A Conversation About Mark Cohen’s Dark Knees

May 7, 2014 | by Jason Fulford and Leanne Shapton

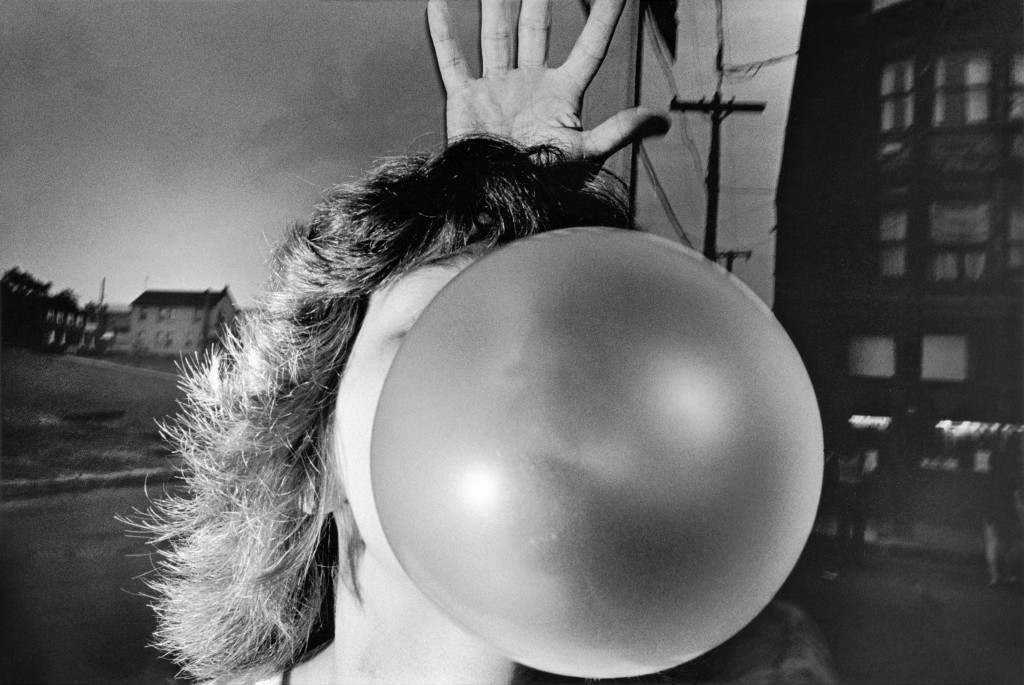

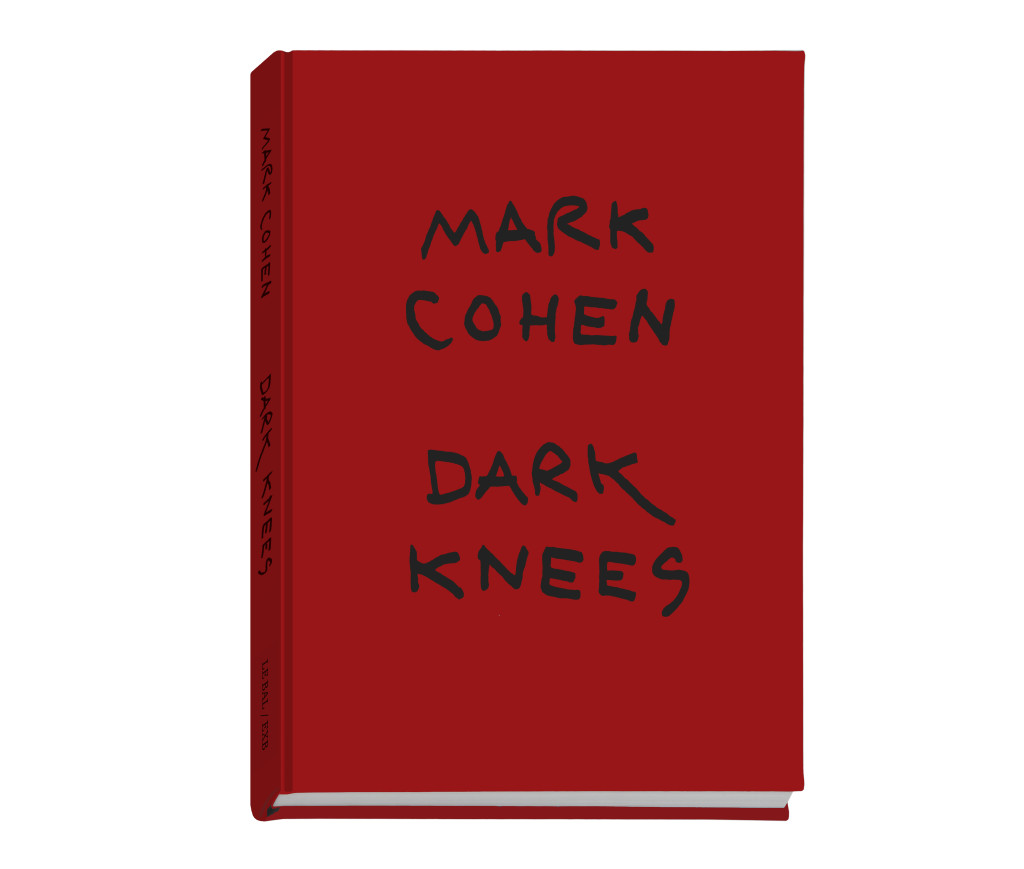

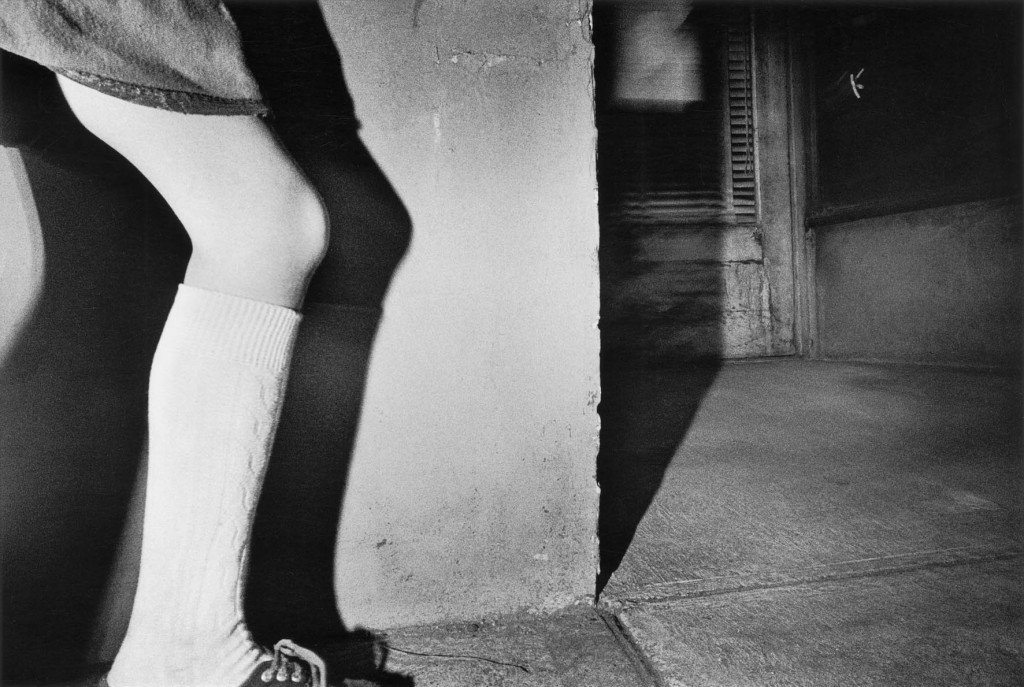

Dark Knees is a 2013 book that accompanies a recent exhibition of Mark Cohen’s photographs from the 1970s, though it feels more like a cryptic archive of fragments—tightly cropped, mostly black and white pictures of parts of the body and objects on the ground. Cohen was born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, where he’s lived and worked for the last seven decades.

Leanne Shapton and Jason Fulford are the founders of J&L Books.

Jason Fulford: I saw Cohen’s show at Le Bal. It was funny to see photographs of Pennsylvania in Paris. I’d like to meet him. I saw a video of him shooting on the street in 1982. He’s pretty sneaky—getting up really close to somebody and then flashing and moving away fast, no conversation. I think he has a thing for legs and feet.

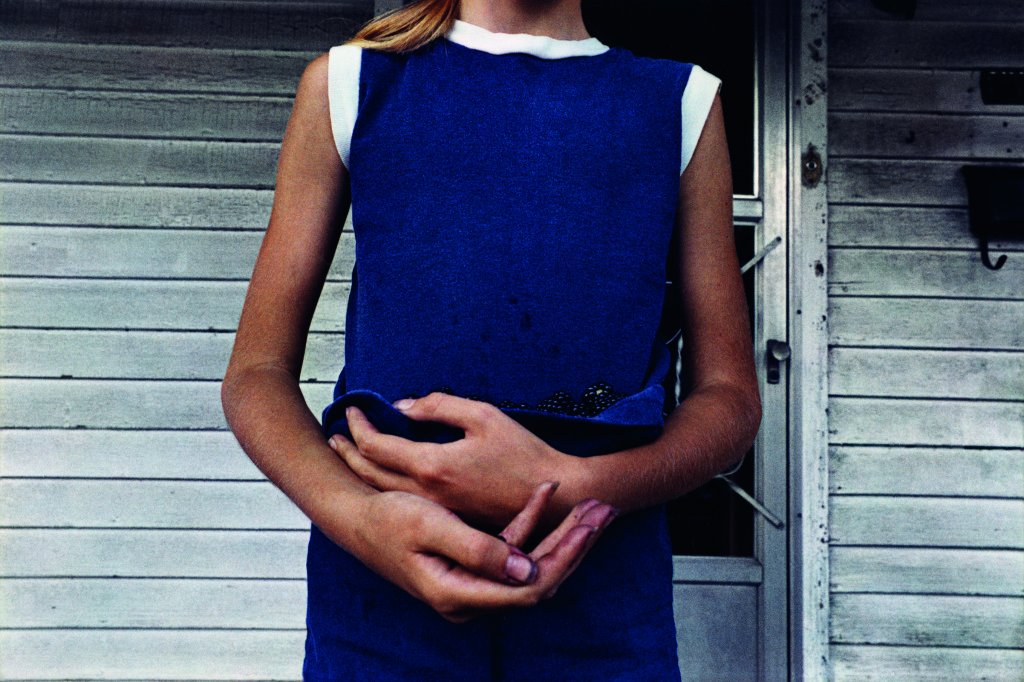

Leanne Shapton: Girls, legs, midsections, hands.

JF: He cites surrealism as an influence. Body parts. I wouldn’t call them portraits. They’re more like pictures of clothes on people.

LS: I’d like to see that footage of him. Looking at the work, it does feel he’s moving, he sneaking, he’s snatching, and it’s almost like he’s looking out of the corners of his eyes. You don’t feel the fixed point with him—you feel it’s sidelong, that he doesn’t want to engage directly.

JF: I kind of wish I hadn’t seen the video. Have you ever seen footage of Daido Moriyama photographing in Tokyo? He uses a point-and-shoot camera and he’s very casual about it. His arms are hanging down straight with a camera in one hand. He moves through the city like a shark, slowly and methodically, in and out of stores, in and out of malls and alleyways, up and down escalators and stairwells, and his instincts seem honed to know when to shoot from the hip and when he can stop and compose. But he never gets that close to people. Cohen shoots with a wide-angle lens, so when he’s got a close up of a face he’s really only a few inches away. Also, it was a different time—people related to cameras differently. In high school, in the eighties, I used to go to the airport and take pictures of people. You can’t do that so easily now. Security won’t let you, people won’t let you. That’s the striking thing about the video of Cohen shooting—people hardly react to him.

LS: Do you think these pictures were edited by him then—in the seventies—or now? The feeling I get just turning the pages is that it’s speaking to what we’d appreciate now—not the feeling that I get from, say, those Lee Friedlander books that were shot and published in the seventies and eighties, which feel “of the time.” Always kind of a funny tension when you find old work. Makes me think of Vivian Meier’s stuff—what work she felt was her best and what we think is her best. It makes me want to say to photographers, Publish work now. Don’t wait till you can edit it in retrospect years later.

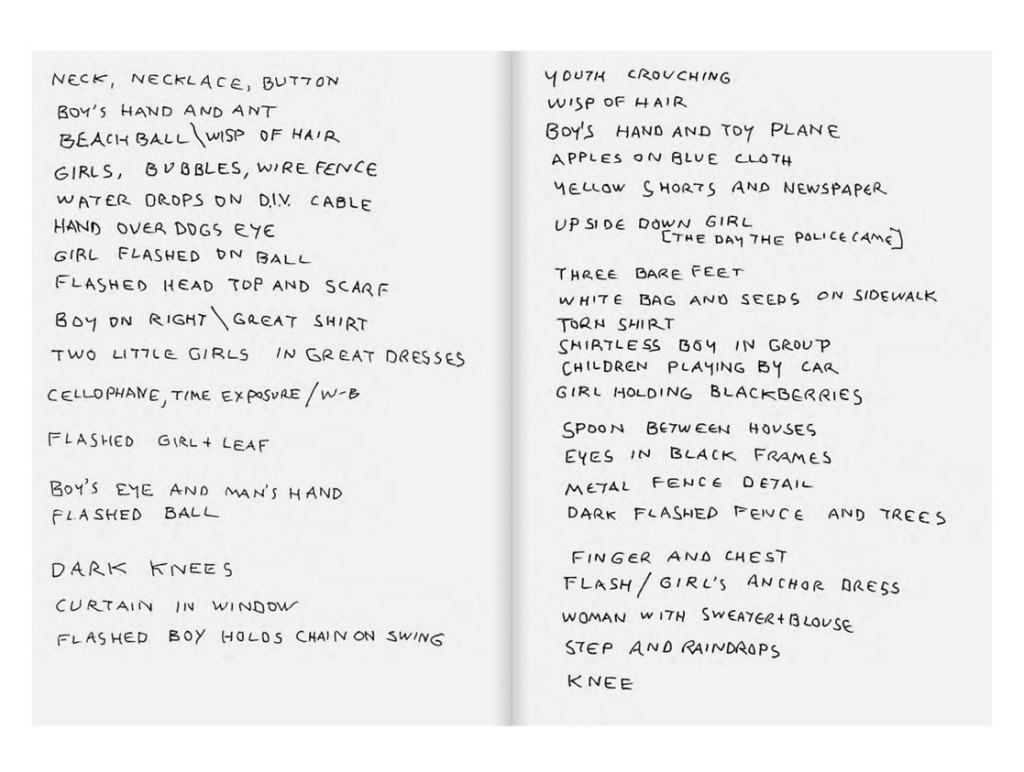

JF: Cohen would shoot in the day, come home and develop the negatives, make dinner, and then edit the work. He says he’s never gone back to the images he initially rejected. But they’re all sitting there still, in his archive. I’d guess that Diane Dufor, the curator at Le Bal, edited this work with Cohen for the Paris show and for the book. The pictures are titled with simple words or phrases. Sometimes they’re obvious—Three Bare Feet—but then sometimes they make you reconsider the picture—Boy Stands in Front.

LS: And they’re handwritten, the titles. I have such an uneasy relationship with hand lettering, considering I do it so much myself. It can look annoyingly naïve, as if you want to send a message of authenticity or childlike wonder. But here—I don’t know why—it works. Maybe because of his age.

JF: I love old-man handwriting. I can’t wait. I’m going to write a lot of letters when I get old. In the exhibition, the walls were painted red and the images were in small frames all in a line across the room. He hand-wrote the titles beneath them, directly onto the wall, with a light blue grease pencil. It was beautiful.

LS: Lets talk about the book as an object. What do you think of the title, Dark Knees? It’s a title from one of the pictures.

JF: I like it. A lot of his photo titles could have been used as book titles—Food Particle Alpha, Cell Phone and Shirt Out, Crack Glass, Meat and Hook, Plane of Snow, Parallel Arms, Cartwheel Bellybutton, White Tire, Improvised Beach.

LS: There’s something about it being a vertical format book with horizontal images that makes you take it in with more movement. An up-and-down read does something different than a left-to-right, because I think you do take both pictures in at once. We’re so used to reading left-to-right, where we can isolate a page in our head, and thus our vision, pretty easily. But this way it feels like a scroll. I’m still jarred by it—it’s more the way a filmstrip works.

JF: You were making a book once, and we were talking about not wanting people to flip through it so quickly, so you requested a deckled edge, which makes it impossible to flip through because you only get chunks of pages. This format does a similar thing—you can’t flip through it. I love this book. I think it’s one of my favorite books of 2013. I wonder if I feel some northeast Pennsylvania kinship with him—I have a connection to Scranton.

LS: Where do you think Cohen falls in the seventies “social landscape” scene—in the Winogrand, Friedlander, Arbus group?

JF: I think he stands apart from that group, literally because of his geographical isolation but also because of his tight cropping of things. Feet and legs. I read a book recently about the Black Dahlia murder and how the surrealists were way into it, following it in the news. And then they all made art using women’s body parts. Hans Bellmer and Man Ray and Dalí and Duchamp. It was creepy. That particular murder had a huge impact on the visual art of the time. I was looking for the influence of surrealism in Cohen’s work.

LS: I see more Magritte—the face obscured, the idea of air and space and sky, melons and apples, you know? Large things looming.

JF: The object taken out of context, mysterious.

LS: Yes, isolated. I’m not a huge fan of surrealism—I like fur-lined teacups and Man Ray, but, ugh, women’s body parts. It just feels like that stage in art school when you photograph mannequins.

JF: I think there’s something more sinister to it.

LS: Yeah. Body parts can seem very “Eroticism 101”—and violent, too—but I don’t get much violence in Cohen’s work. He’s more a peeping tom.

JF: I get the sense that he takes pleasure in seeing what something will look like as a photograph. I think it was Winogrand who said he just wanted to see what something would look like photographed. But with Cohen, using a flash and flattening surfaces is sometimes not about capturing what’s actually happening there. It’s about turning it into something else, a flattened thing.

LS: That’s such a modern state of being, knowing and understanding and wanting to see something as a photograph. That’s the story of the last century. It’s how we look at the world now by default.

JF: I just watched a documentary about Michelangelo Antonioni. They interviewed a lot of people who loved him, and one was Alain Robbe-Grillet, who talked about Antonioni in contrast to Hitchcock. When Hitchcock shows you things onscreen, sometimes they’re confusing, but by the end of the film he wraps everything up and it all makes perfect sense. Robbe-Grillet says that Antonioni is the opposite—everything makes sense in the moment, but as the film goes on, it makes less and less sense. The meaning actually opens up rather than closes. He says that modern work opens up meaning.

LS: I like that definition, but I don’t think it applies to what I was saying. I’m thinking of the moment where we take ourselves out of a situation to photograph it, and then we look immediately at the five frames we’ve taken on our device to find the one that most satisfies us. We already have a preconceived notion of what we’re going to get in the frame.

JF: Jeff Ladd was talking about this recently. He says that when you use a digital camera, you see the results immediately, and stop shooting once you’ve got what you set out for. But when you use film, there’s more uncertainty, so you keep shooting, and often the more interesting pictures are the ones that happen seven or eight frames later—that you never would have gotten to digitally. Cohen used a flash at close range. There’s one picture, Knee—he says when he took the picture, he was just shooting a girl’s knee, but in the end the whole composition, the way the shadows and angles line up, make the picture transcend the knee.

LS: You said you like the idea of him—what do you mean?

JF: He stayed in the town where he grew up, and he’ll probably die there. He had a few successes outside, but he went back. I respect that.

LS: It’s honest and straightforward and in some ways modest. I was just reading about Stephen King, who still lives in Maine. Knowing something so intimately makes for good art—when you’re an observer and an insider.

JF: Every town should have a Mark Cohen. Someone who sticks around, someone who looks at the town through a surrealist lens.

LS: The resident insider. It’s a noble calling.

Mark Cohen maakt foto’s als een haastige jager

Door RIANNE VAN DIJCK15 OKTOBER 2014

Natuurlijk, de meeste mensen geloven niet dat een foto een stukje van hun ziel wegneemt. Maar dat fotografie iets roofzuchtigs heeft, zoals Susan Sontag beweert, dat klopt wel. Zeker bij straatfotografie, waarbij in principe elke burger vogelvrij is.

●●●●○ Mark Cohen: Dark Knees

T/m 11/1 in het Nederlands Fotomuseum. Rotterdam. Inl: nederlandsfotomuseum.nl

Als je op internet filmpjes bekijkt over de werkwijze van de Amerikaanse straatfotograaf Mark Cohen (1943), zie je een roofdier aan het werk. Cohen besluipt zijn onderwerpen als een leeuw, op zoek naar dat ene, bijzondere moment. Om zijn prooi op het moment suprême te overvallen met een kleinbeeldcamera in zijn ene en de flitslamp in zijn andere hand. Het volle licht flitst in het gezicht van de nietsvermoedende voorbijganger, die de fotograaf verschrikt en verbaasd aankijkt. En voordat hij beseft wat er gebeurd is, heeft de hyperallerte Cohen allang weer de benen genomen. Hij komt veel te dichtbij, duikt omlaag en brengt razendsnel zijn camera in de aanslag. Zonder door de zoeker te kijken drukt hij af. Snap. Snap. Snap. Buit binnen.

In de tentoonstelling Dark Knees van Mark Cohen in het Nederlands Fotomuseum in Rotterdam, zien we in 130 foto’s de resultaten van de omzwervingen die hij tussen 1969 en 2012 maakte door de straten van Wilkes-Barre, een voormalig mijnstadje in Pennsylvania. Hij werd er geboren, woonde er bijna zijn hele leven en runde er een fotostudio. Tussen de trouwpartijen en commerciële opdrachten door legde hij de vluchtige momenten in het dagelijks leven vast. De man achter een flipperkast, de arm van een oude vrouw die wat blaadjes uit een heg trekt, de vuile knieën van een kind. Hij fotografeerde de paarse broek van een meisje met een springtouw, de jas met pantermotief.

Mark Cohen besluipt zijn onderwerpen als een leeuw

Op de foto’s staan vooral veel handen, voeten, benen, buiken, dijen. Zelden een heel lichaam, en zelden een gezicht – meestal is dat sowieso onherkenbaar omdat het maar half in het kader past, of omdat een grote kauwgombel het zicht belemmert. Als hij geen (delen van) mensen fotografeert, focust Cohen op ogenschijnlijk volstrekt oninteressante taferelen: een oude houten deur, een plastic zakje op het gras, lege flessen op een rij. Tezamen vormen de beelden een poëtisch portret van een stad, of eigenlijk meer een glimp van een geheime, bijna mysterieuze wereld achter die stad. Dat devote samenvouwen van de handen in de schoot, de zachte dauwdruppels op de waslijn, het priemende oog van de hond die zich nog net het kader weet binnen te wringen. Als Cohen ze niet voor ons had vastgelegd, zouden ze ons waarschijnlijk nooit zijn opgevallen.

We zien dit soort beelden de laatste jaren wel vaker opduiken; de fragmentarische snapshots via de smartphone, die soms tot kunst worden verheven. En in de zogeheten found photography, oude albums of losse foto’s, nooit bedoeld voor de witte muren van een galerie of een museum, totdat een marktstruiner met oog voor esthetiek het stof ervan afblies.

Net als het werk van Cohen roepen deze nieuwe vormen van omgaan met fotografie vragen op over privacy. Want eigenlijk is zijn werk een beetje ongepast, net iets te dichtbij, voyeuristisch. En net als de smartphonebeelden en de gevonden beelden zijn de foto’s van Cohen verre van perfect: overbelicht, onscherp, het onderwerp amper in beeld. Maar juist dat rafelige randje, gecombineerd met dat ultieme oog voor detail, geeft zijn foto’s die enorme kracht.

Een versie van dit artikel verscheen op woensdag 15 oktober 2014 in NRC Handelsblad.

Op dit artikel rust auteursrecht van NRC Handelsblad BV, respectievelijk van de oorspronkelijke auteur.

Een versie van dit artikel verscheen op woensdag 15 oktober 2014 in NRC Handelsblad.

Op dit artikel rust auteursrecht van NRC Handelsblad BV, respectievelijk van de oorspronkelijke auteur.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten