zondag 23 december 2018

Views & Reviews Intersections Africa in the PhotoBook David Goldblatt Photography

‘Intersections’ is the term used by the South African photographer David Goldblatt for the crosscurrents of values, ideas, standpoints, spaces and people that comprise South African society. Goldblatt (b. Randfontein, 1930) is the éminence grise of South African photography, known for his subtle and sharp take on life in South Africa. With the exhibition Intersections, Huis Marseille is the first to present a large survey of Goldblatt’s new colour photography in the Netherlands.

Critical Observer

David Goldblatt works in the tradition of the great documentary photography of the 20th century. From the time when the apartheid regime was introduced at the end of the 1940s, he has observed social developments in his native country with a critical eye and a specific attention for the neglected detail. Goldblatt is not a photojournalist who reports on obtrusive events; he is more interested in recording the social conditions that lead to those events. His photographs of mine workers, Afrikaners, life in the black homelands and in the white suburbs are published in magazines and books, such as On the Mines (1973), Some Afrikaners Photographed (1975), In Boksburg (1982), Lifetimes under Apartheid (1986), The Transported of KwaNdebele: A South African Odyssey (1989), South Africa: The Structure of Things Then (1998) and Particulars (2005). With the book Intersections (see below), a new title has now been added to the list.

Although Goldblatt has been one of the most prominent of South African photographers for almost half a century and had a solo exhibition in 1998 in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, he gained fame in Europe relatively late. The 11th Documenta in Kassel (2002), where black-and-white photos from the In Boksburg series and photos of Johannesburg from the Intersections series were shown, increased interest in his work, as did Fifty-One Years (2001), a retrospective of Goldblatt’s work presented in Witte de With in Rotterdam and elsewhere.

Goldblatt investigates how apartheid and the country’s violent history have shaped its political and social structures, its cities and landscapes. Through his photography he attempts to give meaning to the relationship between the political and physical geography of South Africa, a connection that is visible in the sometimes subtle changes at work in the cities and especially in the overwhelming South African landscape. As he once said in an interview: Primary is the land, its division, possession, use, misuse. How we have shaped it and how it has shaped us. This personal and simultaneously political vision earned him the prestigious Hasselblad Award in 2006.

Colour

Until a few years ago Goldblatt’s ‘personal’ work was exclusively in black and white, for with colour he could not express his rage, revulsion and fear of the ideology of apartheid. Moreover, during that period he had found the technical expressive possibilities of colour photography to be limited: for example, colour transparency films had not enough latitude, colour negatives displayed colour casts, and he did not have sufficient control over prints made on PE paper. The beginning of a new political and social era after the abolition of apartheid occurred almost synchronously with far-reaching developments in digital printing techniques. At this point Goldblatt felt the need to expand his choice of subject and form of expression. A new generation of colour films and the remarkable control of contrast and colour saturation enabled by digital reproduction have made that possible for him.

Goldblatt shoots his photographs on colour film and then edits the negatives in the computer. Working together with his master printer Tony Meintjes, he only makes changes that could be done in a darkroom – he never uses the computer to alter the contents of an image. The prints are extremely sophisticated inkjet prints on aquarelle paper. He strives for a colour rendering which corresponds as closely as possible to his perception of colour in the reality of the harsh South African sunlight. High contrasts, unsaturated, neutral colours and at the same time a broad range of tone and hue give each print an unprecedented, pinpoint sharp graphic quality in which each detail is visible.

Themes

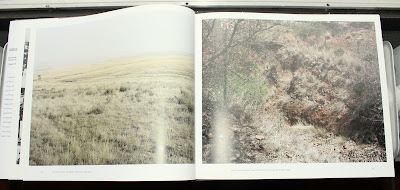

Goldblatt’s masterful command of photographic techniques is sublimely expressed in his series of monumental photographs of the desolate, desert-like landscape of the Karoo and the Northern Cape province. The temperatures are extreme, it is arid and dry, and the sun shines intensely and mercilessly in the immense sky. Every colour fades in this endless landscape in which the lack of reference points throws the traveller upon his own resources. Goldblatt tries to reveal the uncompromising character of this landscape in his photographs. He avoids optical tricks (wide-angle, panoramic photography) and the picturesque and dramatic moments of the day (sunrise, sunset, stormy weather). With his view camera he achieves a great depth of field that enables the reviewer to ‘read’ the image down to the smallest detail. Only in this manner can he collect the visual proofs of the relationship between mankind and the land: fences, monuments, remains of settlements, nomads and their herds, et cetera.

The content and intensity of Goldblatt’s colour photography is not fundamentally different from that of his older black-and-white work. But he does take into account the specific possibilities of colour photography. Intersections contains themes that he never could have satisfactorily depicted in black-and-white, such as the series of asbestos landscapes which touch on a large social problem. Blue asbestos was mined for a century in South Africa but the companies doing this ignored the damage done by asbestos to the health of mining communites and the dangers of asbestos waste scattered over the land they mined. Thousands of people have died as a result and many more will follow in years to come. The new government supports claims made by the relatives and at great cost it is rehabilitating the environment.

During apartheid, blacks were only allowed to appear on the streets of Johannesburg under strict conditions and were not permitted to do business. After collapse of apartheid millions of people poured into South Africa’s cities from all over Africa. Within a few years Johannesburg city became heavily overcrowded and populated almost entirely by blacks. Its streets were radically transformed from sanitised post-colonialism to a vigorous if sometimes chaotic Africa. There being few job opportunities the informal economy grew exponentially. With a few apples and some sweets you could become a hawker. With a paint brush, a cell phone and some hand-made advertisements on suburban sidewalks, a man could be in business. Meanwhile most whites and well-to-do blacks moved to new suburbs where they entrenched themselves in fortress-like housing that is not-quite impregnable against violent and ingenious criminals. Goldblatt’s photographs have pin-pointed some of these developments.

Goldblatt believes that much of South African society’s ethos and values have been expressed non-verbally in its built structures. In his book South Africa the Structure of Things Then (1998) he attempted to elucidate this belief in black and white photographs of the structures of racial domination and apartheid. Many of his Intersection photographs explore these ideas in colour in the land and cityscape of post-apartheid South Africa, taking in, among others, changes to old monuments, the coming of new ones and the proliferation of personal commemorations.

With the coming of democracy there have been fundamental changes in the system and constituents of government. New officials and representatives have come into office and new power structures have been created. Goldblatt has looked at some of this transformation at the local, municipal level of government.

AIDS

Several of Goldblatt’s most recent works have also been included in the exhibition in Huis Marseille, putting a new accent on the most topical and urgent problem in South Africa: HIV-AIDS. South Africa has one of the highest percentages of HIV-AIDS victims in the world. Although there are signs of change, the government has reacted less than decisively, even to the extent of denying the problem in the past. Incidence of the disease is highest among the poor, and those afflicted are often ashamed to declare their status. There are several public campaigns to heighten awareness of the disease and of safe sex, among them is the ‘planting’ of the ‘AIDS ribbon’ in the social landscape where, as Goldblatt’s photographs show, it is often submerged and seemingly forgotten.

In response to the room with David Goldblatt’s most recent ‘AIDS Landscapes’ in Huis Marseille, Han Nefkens has decided to acquire ten works for the Huis Marseille / H+F Collection, with the aim of showing the photographs in a separate travelling exhibition dedicated to the theme of AIDS. This aim is in line with the programme to combat HIV-AIDS that the H+F Collection addresses and stimulates. At the opening of Intersections on 10 March, Han Nefkens will make explanatory remarks on the purchase.

Intersections was realized in close collaboration with David Goldblatt and the museum kunst palast in Düsseldorf, where the exhibition was shown earlier.

Publication

Prestel Verlag in Munich has published the eponymous book, which will be available during the exhibition in Huis Marseille. The book contains an interview by Mark Haworth-Booth with the photographer and texts by Michael Stevenson and Christoph Danelzik-Brüggemann. ISBN 3-7913-3247-3, language: English,

At Kevin Kwaneles Takwaito Barber Shop on Lansdowne Road, 2007, © David Goldblatt

Ellerines, Beaufort West, Western Cape in the time of AIDS, 2007, © David Goldblatt

Woman sunbathing, Fellside, Johannesburg, 1975, © David Goldblatt

Land van toiletpotten

Decennialang fotografeerde David Goldblatt de asbestlandschappen in zijn geboorteland, maar ook de zwarte thuislanden en de witte suburbs. „Ik heb altijd al een analytische benadering tot het leven gehad.”

Rosan Hollak

16 maart 2007

‘De molen van de Pomfret Asbestmijn die in gebruik was van 1978 tot 1986 toen de mijn werd gesloten, Pomfret, North-West Province, 20 december 2002’

Fernando Augusto Luta washes his clothes while Augusto Mokinda (13), Ze Jano (12) an Ze Ndala (10) pose for a photograph in the water in which they swim in a mineshaft of the Pomfret Blue Asbestos Mine, Pomfret, North-West Province, 25 December 2002.

‘De molen van de Pomfret Asbestmijn die in gebruik was van 1978 tot 1986 toen de mijn werd gesloten, Pomfret, North-West Province, 20 december 2002’ Fernando Augusto Luta washes his clothes while Augusto Mokinda (13), Ze Jano (12) an Ze Ndala (10) pose for a photograph in the water in which they swim in a mineshaft of the Pomfret Blue Asbestos Mine, Pomfret, North-West Province, 25 December 2002.

Goldblatt, David

Blauwe asbest. Ooit had een vriendin van de Zuid-Afrikaanse fotograaf David Goldblatt (76) een klein brokje in haar huis liggen. Ze speelde er af en toe mee en liet het dan weer rondslingeren. Een tijd later kreeg ze een vreselijke vorm van longkanker. Ze overleed binnen een jaar. „Eén piepklein deeltje van deze materie in je longen kan de ziekte al veroorzaken”, zegt Goldblatt, in Amsterdam voor Intersections, een overzichtstentoonstelling van zijn nieuwe kleurenfotografie in Huis Marseille.

De dood van die vriendin, een boerin die nog nooit in de buurt was geweest van een asbestmijn, was voor hem aanleiding om in 1999 een serie te starten over asbestlandschappen. „Al meer dan een eeuw wordt blauwe asbest in mijn land uit open groeven ontgonnen. Het gebied waar deze mijnen zich bevinden bestrijkt een oppervlakte van zo’n 450 kilometer breed. Veel van het afval is nog steeds niet opgeruimd en ligt op het land.”

De bedrijven die dit mineraal uit de grond halen, waaronder het internationale concern Cape dat inmiddels is gesloten, bekommerden zich nauwelijks om de gezondheid van de voornamelijk zwarte mijnwerkers. Duizenden arbeiders die voorheen werkzaam waren in de Cape-mijn zijn aan asbestkanker overleden. „Bovendien is het leven van honderdduizenden omwonenden er ook door aangetast”, zegt Goldblatt. „De bedrijven hebben na sluiting van de mijnen de medewerkers zonder enige vorm van zorg achtergelaten. Gelukkig worden de mijncoöperaties mondjesmaat door nabestaanden aangeklaagd en is de nieuwe regering bezig het landschap voor veel geld te saneren.”

Goldblatt, die al meer dan vijftig jaar werkzaam is, staat bekend als de ‘nestor’ onder de Zuid-Afrikaanse fotografen. Gedurende de afgelopen decennia fotografeerde hij het leven in de zwarte thuislanden en in de witte suburbs, publiceerde hij in talloze tijdschriften en maakte boeken zoals On the Mines (1973), In Boksburg (1982), Lifetimes under Apartheid (1986) en South Africa: The Structure of Things Then (1998). In 1998 had hij een solo-expositie in het Museum of Modern Art in New York en Witte de With in Rotterdam toonde in 2002 de expositie Fifty One Years.

Voor zijn recente serie over asbest maakte hij geen portretten van doden of slachtoffers, maar wel, met een Japanse veldcamera, vlijmscherpe beelden van de blauw-grijze vezels op het land, van verlaten mijnschachten en van een spookachtig verlaten fabriek.

Deze invalshoek is typerend voor de levendige, door de zon gebruinde Zuid-Afrikaan, die er niet uitziet als iemand die de tachtig nadert. Goldblatt, die opgroeide in een blank, joods middleclass-gezin in het stadje Randfontein, is een geboren avonturier. Sinds het apartheidsregime eind jaren veertig werd ingevoerd, toert hij rond door zijn land en observeert de maatschappelijke ontwikkelingen. Hij doet dit door foto’s te maken die vragen om aandacht en interpretatie, vaak met een groot gevoel voor detail.

Zo toont een oudere foto van zijn hand uit 1962, getiteld A Plotholder and the Daughter of a Servant, een oude blanke landeigenaar met zijn zwarte bediende. Het lijkt een simpel bewijs van de apartheid maar wie goed kijkt, ziet dat het zwarte meisje zich buitengewoon op haar gemak voelt in het huis van de oude pachter. Hun verhouding is niet zwart-wit. Ze staan niet tegenover elkaar. Integendeel. En dat is wat hij vaak laat zien. „Ik heb altijd al een analytische benadering tot het leven gehad. Gedurende het apartheidsregime was niemand heilig. We all had different shades of grey.”

Goldblatt interesseert zich meer voor de maatschappelijke omstandigheden die tot een gebeurtenis leiden dan dat hij de gebeurtenissen zelf wil vastleggen. „Het gaat mij erom hoe mensen hun normen en waarden uiten in hun gedrag, lichaamstaal, kleding en gebouwen.” Vanwege deze persoonlijke en politieke visie op de maatschappij werd hem in 2006 de Hasselblad Award toegekend.

De foto’s die nu in Amsterdam zijn te zien zijn allemaal in kleur. Tot een paar jaar geleden maakte Goldblatt zijn vrije werk vrijwel uitsluitend in zwart-wit. „Voor mij was dat de manier om de woede, de angst en het afgrijzen van wat er in mijn land plaatsvond uit te drukken. Zwart-wit heeft gewoon meer kloten.”

Pas toen de digitale afdruktechnieken echt verfijnd raakten, ging Goldblatt over op kleur. „Toevallig liep de afschaffing van het apartheidsregime in 1990 zo’n beetje synchroon met de nieuwe ontwikkelingen in digitale afdruktechnieken.” Voor het maken van kleurenprints werkt hij veel samen met drukker Tony Meintjes. „Hij scant mijn negatieven. Samen kijken we naar het beeld en versterken of verzachten de kleuren. Soms verhogen we het contrast. In feite doen we hetzelfde als wat ik voorheen in de donkere kamer deed. Ik bewerk het beeld, maar wat erop staat, verander ik niet.”

Veel foto’s die nu in Huis Marseille te zien zijn, tonen het enorme desolate landschap van de Karoo en de Noord-Kaap. Het zijn verstilde, ingehouden composities van dorre, oneindige landschappen waar de hitte en eenzaamheid bijna voelbaar is. Vaak schuilt er achter één foto een hele geschiedenis. „Mijn ideaal is om het verleden en het heden tegelijkertijd te vangen. Ik probeer iets wat heel complex is, in één keer weer te geven. Het gaat vaak om het paradoxale of het ironische van een situatie. Je kan het misschien het beste vergelijken met de gelaagdheid uit de boeken van Zuid-Afrikaanse schrijvers als J.M. Coetzee of Nadine Gordimer.”

Als voorbeeld noemt Goldblatt een beeld dat hij recent maakte in Oost-Kaap waar, midden in een desolaat landschap, de restanten te zien zijn van een toilet. „Dit noemen wij een long-drop lavatory,” zegt Goldblatt lachend, terwijl hij de foto laat zien. „In feite is het een gat in de grond waar je in poept. Ik was voor het eerst op deze plek in 1983, er stonden toen 1500 toilethokjes op een berg.” De wc’s waren daar neergezet door het apartheidsregime en maakten deel uit van de Frankfurt-nederzetting. De woonplek was opgericht voor de Mgwali, een zwarte gemeenschap van 5000 man, die zo’n 100 kilometer verderop woonden. „Deze mensen moesten gedwongen verhuizen omdat de plek waar zij tot dan toe woonden was uitgeroepen tot een ‘black spot’: een stuk zwarte grond in een door blanken bewoond gebied.” Volgens Goldblatt zijn er in Zuid-Afrika meer toiletten gebouwd dan in welke andere beschaving uit de geschiedenis dan ook. „Als je grote aantallen mensen gedwongen wilt verplaatsen, moet je met één ding goed rekening houden: ziekte. Want ziekte maakt geen onderscheid in ras. Daarom worden er héél véél toiletten gebouwd.”

Omdat de Mgwali na vijf jaar strijd weigerden te verhuizen, bleven de toilethokjes doelloos in het landschap staan. „Mensen in de buurt gingen gebruik maken van het bouwmateriaal. Toen ik er in 1990 opnieuw langs ging, waren er alleen nog kleine witte plastic stoeltjes overgebleven. En toen ik er vorig jaar weer met mijn vrouw langsging, waren het alleen nog maar gaten in het veld. Ze zijn dus gereduceerd tot een onherleidbaar minimum.” Wat hem het meest intrigeert aan deze toiletpottengeschiedenis is de vorm. „Ze zijn gevormd in overeenstemming met de menselijke anatomie!” lacht hij. „Waarom die kleine uitstulping? Een extra ruimte voor de man voor als hij gaat zitten?”

Sinds eind jaren negentig wijdt Goldblatt zich voornamelijk aan zijn persoonlijke werk. Hij woont in Johannesburg, maar zodra hij de kans heeft trekt hij erop uit met zijn camper. Dan reist hij weken door het land. Soms alleen, het liefst met zijn vrouw. Maar over het algemeen heeft hij het gevoel dat hij nergens bij hoort. „Ik haat het om tot een groep te behoren. Dat ligt voor de meeste Zuid-Afrikanen anders. Iedereen is lid van een politieke partij of een sportclub. Maar wat dat betreft denk ik niet dat ik ergens thuishoor.”

Goldblatt heeft altijd zoveel mogelijk geprobeerd zelfstandig te werken, zonder enige vorm van verplichting aan wie dan ook. Onder het apartheidsregime, toen hij ook veel commerciële opdrachten had, accepteerde hij nooit geld van de regering. „Ik probeerde alles wat politiek onacceptabel was te mijden. In die tijd werd je al snel beschouwd als een propagandist voor de regering. Of anders was je wel een activist.” Toen hij eind jaren tachtig een expositie in Londen had, werd hij een tijd door het ANC geboycot. „En ik ben ook wel eens door een reclamebureau gebeld dat mij een vrije opdracht gaf. Ze zeiden; wij betalen je, doe wat je wilt, maar fotografeer de waarheid over Zuid-Afrika. Ik vroeg: wiens waarheid? Uiteindelijk bleek dat ze toch wilden dat ik de Zuid-Afrikaanse regering zou propageren.” Een activist is Goldblatt dus niet. Een fotojournalist evenmin. Hoe noemt hij zich dan wel? „Eigenlijk ben ik een zelfuitverkoren, onbevoegd sociaal criticus”, zegt hij grijnzend.

Sinds er in 1990 een einde kwam aan het apartheidsregime zijn de sociale en politieke structuren flink veranderd. Maar nog steeds zijn er meer dan genoeg maatschappelijke kwesties die Goldblatt op zijn eigen, subtiele wijze in beeld brengt: „Je ziet nu veel oude monumenten waar een ijzeren hekwerk omheen is gebouwd. Dat is om te voorkomen dat het metaal wordt gestolen. Ik ben al een paar keer langs een plek gereden waar een groep huizen staat, helemaal af, maar er woont niemand. Ik vermoed dat hier contracten zijn getekend en bouwvergunningen afgegeven terwijl er onvoldoende mensen in de omgeving wonen om die woningen te betrekken. Corruptie is echt een groot probleem in mijn land.”

Toch is Goldblatt zeer te spreken over de veranderingen die Zuid-Afrika in de afgelopen jaren heeft doorgemaakt. „Dit land heeft nog steeds een heleboel negatieve kanten: er is criminaliteit, armoede, geweld, dingen werken niet goed en de werkloosheid is groot. Maar we hebben nu een echte democratie, we zijn niet meer bang voor de geheime politie en de huidige regering heeft de economie enigszins weten te stabiliseren. Het nieuwe Zuid-Afrika is een veel betere plek dan het oude Zuid-Afrika.”

Abonneren op:

Reacties posten (Atom)

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten