Lees verder ...

Lees verder ...

New York Photographs 42nd Street in 1997, by Philip-Lorca diCorcia, from “Glitz & Grime” at Yancey Richardson. More Photos >

Multimedia Slide Show

Slide Show

A good place to start is with “Glitz & Grime: Photographs of Times Square” at Yancey Richardson. Twenty-four pictures, dating from 1945 to 2009, chronicle the highs and lows of a place that embodies the spirit of American commercial culture at its most seamy and manically exuberant.

In black-and-white pictures from the 1940s and ’50s by Louis Stettner and Rudy Burckhardt shadowy, walking men in hats and overcoats seem like lost souls in a crepuscular purgatory. That mood is revived in a photograph from as recently as 1997 — well into Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani’s campaign to clean up the Times Square area — by Philip-Lorca diCorcia in which pedestrians seem like extras in a neo-noir or zombie movie.

A big color picture by Andrew Moore registers the nearly psychedelic impact of the signage that’s there now, and Lynn Saville’s partly blurred image of automobile traffic has a lush, cinematic beauty. But if there is joy to be found in Times Square, you wouldn’t know it from this show.

Considering the once tawdry reputation of this crossroads of the world, and the aggressive eroticism of its contemporary advertising, it is odd that there is hardly any sex in the Richardson show. For that you have to go to “Sexy and the City” at Yossi Milo, in which the main attraction is a single-wall, salon-style hanging of 29 mostly black-and-white pictures.

As at Richardson the feeling here is more noirish than celebratory, and there is little romance in this sex. The show is leavened by Charles H. Traub’s funny picture of an elderly woman at the Metropolitan Museum of Art reading a label at the feet of a giant, marmoreal nude man. But Merry Alpern’s grainy, voyeuristic view of a woman in her underwear from a series called “Dirty Windows” and Alvin Baltrop’s distant shots of anonymous men having sex on the West Side piers in the late ’70s and early ’80s are more typical.

The photographers at Yossi Milo are more like underground journalists or sociologists than interested parties. Ryan Weideman’s erotically costumed people in the back of his taxi cab, Diane Arbus’s awkward young couple on a park bench, Nan Goldin’s drag queen out on the street in a huge, rococo wig with nipples exposed: all these images seem possessed of a world-weary remoteness. Hanging on a wall opposite the 29-picture display, Mitch Epstein’s big color picture of a pretty young woman in a taxi with her head back in an apparent state of exhausted ennui seems to sum it up.

If the jadedness of the Richardson and Milo shows brings you down, there’s a good antidote in a selection of photographs, many never seen in public before, by the great Helen Levitt at Laurence Miller. “First Proofs” presents almost 30 trial prints, ranging from matchbook to playing-card size, that Levitt made between 1939 and 1942. It is a fascinating, heartening exhibition.

In Levitt’s images of children at play in Spanish Harlem and the Lower East Side there is not a trace of cynicism. Nor is there anything mean-spirited in her pictures of comically rotund ladies talking on a doorstep or a group of four men who seem clownish archetypes of masculinity, watched over from an apartment window by a little girl with a thoughtful expression. Levitt, who died this year at 95, had a Whitmanesque generosity. Her pictures are loaded with unqualified love, which is something you don’t see a lot of in modern photography.

Thanks to artists like Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince, a more prevalent attitude these days is wised-up skepticism: doubt about the truth-telling capabilities of photography itself and suspicion of its engagement with the machinery of mass culture. Three large-scale pictures by Bill Jacobson at Julie Saul Gallery participate in that postmodern trend with depictions of crowded New York streets that are so out of focus it’s almost impossible to make out their scenes. They could be viewed as works of Neo-Pictorialist poetry, but mainly they call attention to the technology and conventions of photography.

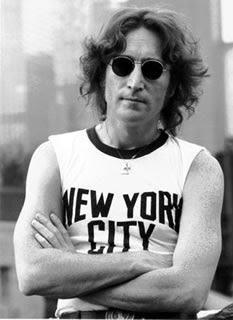

Most people still want to see through photographs to the people, place and things they represent, and that is the appeal at the Bonni Benrubi Gallery of “Live From New York ...,” which rounds up pictures of famous musicians performing or hanging out in the city. Here it’s all about the subject: Billie Holiday, Frank Sinatra, Sonny and Cher in hippie-cowboy outfits, Marilyn Monroe singing “Happy Birthday” to President John F. Kennedy, Bob Dylan and George Harrison in a duet onstage, the Ramones outside CBGB. Except for Arnold Newman’s starkly formal portrait of Igor Stravinsky, in which the black, uplifted piano top occupies most of the picture, few of the photographs are interesting for formal or stylistic reasons.

One has achieved iconic status: Bob Gruen’s 1974 portrait of John Lennon in a sleeveless New York T-shirt, against a backdrop of New York buildings. Lennon once caused a stir by declaring that the Beatles had become more popular than Jesus; for people of a certain age, anyway, Mr. Gruen’s image, resonating with Lennon’s fate on an Upper West Side street six years later, has an uncanny, Christlike mien.

But no photographic subject symbolizes New York like the Statue of Liberty, which is viewed from near, far, above and below in a small exhibition at Hasted Hunt. In one picture by Lou Stoumen from 1939, a man and a woman gaze worshipfully up at the towering torch bearer. In another, made in 1940 by the same photographer, we look down from above her crown and notice someone sticking an arm out the window, the little human hand comically rhyming with the giantess’s fingers curled around her tablet.

Bruce Davidson’s 1959 photograph of the faraway lady of the harbor, just visible through a forest of rooftop television aerials, is a rueful meditation on humanist values that modernity makes more and more difficult to sustain. Some may view the statue as a colossal piece of kitsch, but who wants to imagine New York without it?

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten