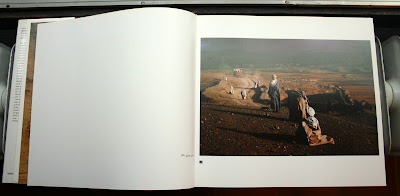

Harry Gruyaert: Morocco

Schirmer Mosel. Fine in Fine dust jacket. 1990. First Edition; First Printing. Hard Cover. 3888145791 . 52 full page color plates. With an essay in French by Brice Matthieussent. 0.9 x 12.6 x 11.9 Inches; 112 pages .

Harry Gruyaert’s Moroccan pictures have the tenacious certitude of mystery. Their content is neither sociological nor ethnographical, and even less so exotic or journalistic. All anecdote is banished, and time—the story, what comes before and after the photograph—appears to be suspended. And yet, it is brimming with energy—the energy of its colors and postures captured on the spot. The enigmatic “subject” of these pictures includes such things as the texture of a wall or the material of a fabric, the composition of the air, and the density that is so specific to Moroccan light, at once violent and tender, glaring and maternal, abstract and sensual. The exact opposite of stereotypical exoticism, Harry Gruyaert shows us what has never been seen before of a different reality that is daily but secret.

Published on 27 July 2015

Harry Gruyaert: “There is no story. It’s just a question of shapes and light”

With the recent release of the first English-language monograph of his work, famed Magnum photographer Harry Gruyaert talks about the banality of colour and the fuzzy line between art and photography

“There is no story. It’s just a question of shapes and light,” Harry Gruyaert says. The storied Magnum photographer is notoriously reluctant to share how he creates his celebrated photography.

As one of the first European photographers to take advantage of the creative potential colour photography held, Gruyaert rarely follows received wisdom — as seen in the first English-language monograph of Gruyaert’s work, published by Thames & Hudson and offering a comprehensive retrospective of his career.

While American photographers such as William Eggleston and Stephen Shore were eagerly embracing the new possibilities of colour, many photographers in Europe of the same generation preferred to relegate it to use in advertising, press and illustration. Gruyaert feels closer to the American approach.

“In Europe and especially France, there’s a humanistic tradition of people like Cartier-Bresson where the most important thing is the people, not so much the environment,” he says. “I admired it, but I was never linked to it. I was much more interested in all the elements: the decor and the lighting and all the cars: the details were as important as humans. That’s a different attitude altogether.”

Kerala, India, 1989. © 2015 Harry Gruyaert / Magnum Photos

This is echoed by artist Richard Nonas, who says “the photographs of Harry Gruyaert have always seemed to me to be images of things, even when they are pictures of people… They are photographs of change, not of movement.”

Gruyaert joined legendary agency Magnum Photos in 1981 and ruffled a few feathers with his more contemporary approach. His influences skewed towards pop culture and away from journalism — not exactly music to the ears of the agency of Robert Capa and René Burri, at the time still largely comprised of black-and-white shooting photojournalists. “Sometimes it was like incredible theatre. it was like a big family where things are sometimes wonderful and sometimes horrible.”

“On my first visit to the States in 1968 and discovering pop art was really important for me. It was completely new, and made me look at banality in a different way, not saying ‘this is bad taste’, [but] to do something with that, accept it and look at it with a sense of humour.”

The impact of pop art is clear — the book opens with TV Shots, his 1972 series photographing distorted TV images.

Living in London, Gruyaert created the series by turning the dial on a television set at random and photographing the distorted images he saw there.

Saturated hues and distorted faces create a nightmarish satire of media culture, and when first exhibited in 1974 caused controversy.

The images, his first serious work, are markedly different from the later work he is renowned for but provides clear context for his career. Despite it all, he struggles with the label of ‘artist’, at least publically. “I don’t know… it’s complicated. I’m saying I’m a photographer and if people think certain things are art, then yeah, sure.”

Paris, France, 1985. © 2015 Harry Gruyaert / Magnum Photos

Gruyaert’s distaste for narrative, coupled with his enduring fascination for the banal, makes him a thoroughly unsentimental photographer. “It’s purely intuition. There’s no concept. things attract me and it works both ways. I’m fascinated by the miracle where things come together in a way where things make sense to me, so there’s very little thinking.”

“When I joined Magnum, I showed [my] pictures of Paris to Raymond Depardon. He said ‘that’s fascinating because you show the banality — the colours of the tables, the plastic of Paris’. It’s an aspect of Paris you don’t see in black-and-white; people are not attracted to that thing, they always want something going on. They want an anecdote.” After such a storied career, perhaps Gruyaert’s refusal to give people what they want is precisely the thing that makes them keep coming back to his work.

‘Harry Gruayaert’ is published by Thames and Hudson now. Details here.

The first solo exhibition of Harry Gruyaert will take place at the Magnum Print Room, 63 Gee Street, London, EC1V 3RS, from 15 September to 31 October 2015

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten