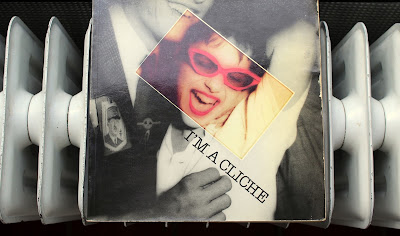

BAUDOUIN. I’m a Cliche.

(Paris): Editions de Nesle, 1979. First edition. Square Quarto. Unpaginated. Increasingly scarce and little known photographic documentation of the early Punk scene in Paris, London and Birmingham. Introductory essay by Marc Villard, text in English and French. A very good plus copy in glossy wrappers. OCLC locates just one copy in the U.S. at University of Colorado at Boulder.

See also

Punk Kids Eighties Paradiso Amsterdam Max Natkiel Photography

rare photos of parisian punks in the early 80s

Memories of the scene preserved thanks to photo booths – "like Amélie, but punk."

It's 2017 and we're still hungry to excavate punk's past. The political and cultural era we now find ourselves in is reminiscent of the late 70s climate — the era that spawned punk. It was tumultuous, deeply divided and marked by rising inequality, though it also saw the rise of a new consciousness and strong pockets of resistance. Conversations about punk usually revolve around England, but across the channel, France had its own tight-knit scene (though cultural recollection is limited by the lack of documentation of the Gallic experience). However, if you dig deep enough and know where to look, you'll come across some gems — like this series of mostly photo booth pictures, taken and preserved by a group of friends who have now shared their punk youth on Facebook. It's a collection of images that captures the fun and freedom of a kind of family, who spent their time making music, filming low-fi videos, dressing up, and raising their middle finger to the world. After we came across these photos we tracked down tracked down Laul, one of the guys in the photos and former member of punk/ no wave band Lucrate Milk, who shared more of his personal archive and gave his account of being a young punk in Paris. Read for more ...

Masto

Belle Journée en perspective : la face cliché du punk

François Gorin François Gorin Publié le 18/10/2013. Mis à jour le 01/02/2018 à 09h01.

1977. Des photographes immortalisent les débuts du mouvement punk à Paris : un curieux mélange de zonards, de travestis et de fils à papa...L'exposition Europunk, à Paris, raconte leur histoire.

Ils étaient trois photographes de 20 ans et quelques, fixant leurs objectifs sur les dérives de la jeunesse des années 70. Issus de deux groupes (on ne disait pas encore « collectifs »), Alain Bali, David Cosset et Jean-Luc Maby en ont monté un troisième, Belle Journée en perspective. Ils démarchent des journaux, des éditeurs. Aux Humanoïdes Associés, Manoeuvre et Dionnet leur suggèrent un sujet rock. Puis un jour : « Arrêtez tout, mettez-vous sur le punk. » On est en 1977. Le trio commence à traîner dans des lieux nocturnes où aucun d'eux n'avait mis les pieds. « Le Gibus, mais aussi une boîte rue Mouffetard, se souvient Maby. Le punk, à Paris, ça se résumait à une bande de vingt zozos qui se retrouvaient tous les soirs. On les suivait, on se mêlait à leur faune, en cherchant surtout à faire des portraits. »

Les chasseurs d'images gardent leurs distances et leur look soixante-huitard, sauf Jean-Luc Maby, le plus caméléon des trois, qui se coupe les cheveux. « On était là en observateurs, raconte Alain Bali, mais il ne se passait rien. » Maby : « Comme l'a écrit Patrick Eudeline [journaliste à Best et chanteur d'Asphalt Jungle, NDLR], une des figures de cette scène avec Alain Pacadis [chroniqueur à Libération], il fallait faire croire aux kids qu'il se passait quelque chose. Tout le monde jouait un peu le clown de lui-même. Nous, on emmagasinait des images en se disant que ça prendrait peut-être un sens, une cohérence. » David Cosset : « Il y avait un phénomène de mode, mais aussi des personnages attachants, qui passaient au studio, situé derrière le siège de l'Unesco, et se racontaient. On faisait aussi de la formation photo ; notre travail a toujours eu une dimension sociale. »

"New boots and panties" in "We are not into music... we are chaos" / © Belle Journée en perspective

Le punk invente un curieux mélange de zonards, de travestis et de gosses des beaux quartiers. Alain Bali se rappelle « un fils d'ancien ministre gaulliste, un dénommé Blaise, qui un jour s'est payé la tête d'Andy Warhol à un vernissage. Tout le monde lui faisait signer des trucs et lui se pointe avec Le Monde, Warhol autographie la une, l'autre insiste et lui tend la page 2, puis la 3, etc. Warhol continue de signer mais s'énerve. A la fin, Blaise prend le journal et y met le feu. Un parfait geste punk ».

Le vrai choc arrive par les concerts. Bali : « J'ai pris une claque avec The Clash au Gibus, un soir à une 1 heure du matin. Quelle énergie ! Joe Strummer crachait, les types au premier rang gobaient ses crachats. » Quand le trio traverse la Manche, il découvre une autre dimension du mouvement, « plus politique, plus working class ». Il se rend à Londres, où le punk est minoritaire mais très présent dans les clubs et les bars ; à Birmingham, où il est bluffé par X-Ray Spex et sa chanteuse Poly Styrene, mais aussi agressé par Ari Up (15 ans), celle des Slits.

"On a tout fait à la façon punk, assez sauvage,

avec des erreurs exprès."

Leur matière, les photographes vont plutôt la chercher dans la salle. Maby : « On travaillait la nuit, surtout au flash ; les prises de vue frontales donnaient quelque chose d'agressif. On estompait ça au tirage en ajoutant du flou. » D'où le style « BJEP », un noir et blanc esthétisé, identifiable, où chacun des trois fondait sa personnalité. Les photos ne sont jamais signées individuellement. Maby : « L'important, c'était de tout assurer nous-mêmes, les planches contact, le tirage, l'editing. Ce système collectiviste a fonctionné pendant cinq ans. » Au bout de huit mois d'immersion, les BJEP apportent leur reportage aux « Humanos » qui le refusent. Maby : « On ne valorisait pas assez les groupes. L'ennui, c'est qu'il n'y avait pas eu de contrat. Presque un an de travail et on se retrouvait à tirer les sonnettes. » Un éditeur-soldeur, Baudouin, accepte finalement d'imprimer I'm a cliché, un livre devenu culte. « On a tout fait, la maquette, les légendes, à la façon punk, assez sauvage, avec des erreurs exprès. » En 1978, l'épicentre du punk parisien s'est déplacé au Palace. Belle Journée en perspective existera encore à travers des expos, des pochettes de disque (Le Chat bleu, de Mink DeVille, Cherchez le garçon, de Taxi Girl...) ou des parutions dans la presse (Actuel, Rock & Folk). Mais l'esprit du groupe a vécu. Les trois compères se dispersent. Il leur reste en commun ce témoignage d'une époque. Bali s'est exilé à Los Angeles, Cosset a longtemps été reporter-images à TF1, Maby fait de la photo d'objets d'art. Eux qui, jadis, ironisaient sur les « artistaillons » grisés par l'appel des cimaises, participent aujourd'hui à l'entrée du punk au musée. Mais sous la forme d'une frise d'une cinquantaine de photos (redevenues nettes). BJEP fondu dans la masse.

Et Christian Chapiron devint Kiki Picasso

A 18 ans, étudiant aux Beaux-Arts, Christian Chapiron voulait refaire le monde, imaginant un Kikiland plein de couleurs. Hippie, il devient punk en 1976. Entre les deux, il a formé le commando Bazooka avec ses amis Jean-Louis Dupré et Olivia Clavel. Un nouveau Kiki est né, baptisé Picasso par dérision. Le flash est venu par la musique : adieu Pink Floyd et Zappa, hello Damned, Sex Pistols et Clash. « A Paris, c'était juste quelques disques, mais à Londres, on pouvait aller d'un club à l'autre et voir cinq concerts punk en un soir. » Le groupe, élargi à six ou sept, partage deux appartements, un goût de la provoc visuelle et l'envie de créer ses propres journaux. « On faisait les choses au feeling, sans hiérarchie ni concurrence, on se repiquait des idées, on montait des coups. » Après quelques titres lancés comme des cocktails Molotov, dont le fameux Bulletin périodique, Bazooka infiltre la presse. En 1977, Libération lui ouvre ses pages. « C'était de la folie totale. On arrivait à 17 heures en évitant les journalistes politiques qui nous haïssaient, et on travaillait jusqu'au bouclage. » S'ensuit le mensuel Un regard moderne, interrompu au bout de sept mois. La belle énergie du groupe s'épuise dans les tensions, les drogues... « Aucun d'entre nous n'était carriériste », résume Kiki Picasso, qui se consacre aujourd'hui au spectacle vivant (le Cirque électrique). « L'art, je n'en ai jamais fait. C'est juste un support de communication. »