Transmuting Forms, Click by Click

The Photographer in Robert Rauschenberg

By PHILIP GEFTEROCT. 17, 2013

Robert Rauschenberg, an artist of towering achievement, painted not only with the brush. He also employed, in his works on canvas, the photographs he took throughout his life, as well as found objects. Although the progression of his work aligns with Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, Pop Art and Conceptual Art, no one movement can claim him. Rauschenberg said that when it came to photography, “the camera is the transport for my eye and carries my seeing from place to place.”

“Robert Rauschenberg and Photography,” at Pace/MacGill Gallery through Nov. 2, explores photography’s role at the center of his work. Assembled are black-and-white photographic prints, shaped photographic collages and bleached Polaroid prints mounted onto aluminum. “What if we begin to think of the entirety of Rauschenberg’s output as essentially a photographic endeavor?” Nicholas Cullinan writes in “Robert Rauschenberg: Photographs, 1949-1962” (D.A.P.), a 2011 book of the artist’s photographs, suggesting that his Combines, performances, silk screens, black paintings and white paintings are all facets of an “essentially lens-based, photographic project.”

Rauschenberg got to Black Mountain College in North Carolina in 1949, where he studied with John Cage, who embraced Zen Buddhism in all aspects of his work, and Josef Albers, who brought the constructivist ideas of the Bauhaus to his teaching. While Cage and Albers would have an abiding influence on Rauschenberg’s work, so would Hazel Larsen Archer, a little-known photographer who emphasized personal vision over technique. Rauschenberg credited Archer with freeing him with the camera, eventually bringing him to the conclusion that photography “is about the eye and not about the hand.”

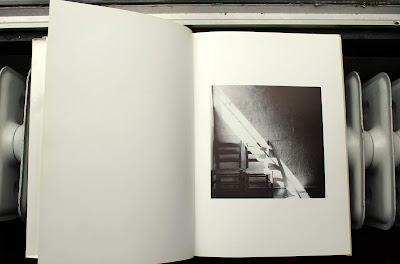

When Rauschenberg studied at Black Mountain, Beaumont Newhall, the photo historian, was in residence; the photographers Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind were teaching there too. The sway of photography became so great that Rauschenberg was unsure whether to pursue painting or photography. With his Rolleiflex, a twin-lens reflex, square-format camera, he photographed the commonplace — sunlight falling on a chair, his foot in wading water, a friend framed by a car window.

In 1952 Edward Steichen acquired two photographs by Rauschenberg for the Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection. Encouraged, Rauschenberg conceived the idea to “walk across the United States and photograph it foot by foot in actual size,” but he then realized the prospect would be impossible. “So maybe I decided I’d just go on painting,” Rauschenberg told Barbara Rose, the art critic. “Then the paintings started using photographs.”

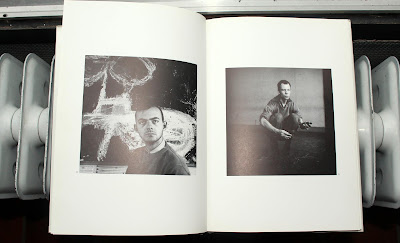

Rauschenberg made his first Combine in 1953, in which a camera bellows and its mount protrude from the canvas. He continued to take pictures, photographing his lovers — Cy Twombly and, later, Jasper Johns — in casual moments at home and during trips through Europe and North Africa. These simple lyric images evoke Alfred Stieglitz’s intimate portraits of Georgia O’Keeffe; Callahan’s photographs of his wife, Eleanor; and Allen Ginsberg’s snapshot-like pictures of Peter Orlovsky, Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs.

Rauschenberg’s street pictures, too, are authentic and spontaneous. “You wait until life is in the frame, then you have permission to click,” Rauschenberg said, equating taking pictures to diamond cutting. “I like the adventure of waiting until the whole frame is full.” Rauschenberg took pictures not only as source material for his Combines, but also, equally, as their own form of creative expression.

In the 1960s photography was still dismissed in the art world as an upstart medium — utilitarian, commercial and journalistic. Yet throughout that decade photographs were hiding in plain sight in museums and galleries, where Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha, John Baldessari and others used them consistently to serve their own conceptual ideas.

In 1963 Warhol made “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men,” a homage to Rauschenberg. On the canvas, using the silk-screen process, he made multiple images of a photographic self-portrait by Rauschenberg as well as pictures Rauschenberg had taken of his family. The title plays off the classic 1941 book by James Agee and Walker Evans to contrast Rauschenberg’s humble Southern beginnings with his growing celebrity. Evans was one of Rauschenberg’s favorite American photographers because of what Rauschenberg described as a “keen reverence for the ordinary.”

Rauschenberg and Warhol both would set the stage for photography to come into its own in the next decade.

Rauschenberg had been incorporating only his own pictures in his work, but when his camera was stolen in 1965, he turned to newspaper and magazine images for source material, resulting in several copyright infringement lawsuits. One stemmed from his use of an image torn out of Life magazine, of a diver, by Morton Beebe for a Nikon advertisement. In 1976, reading a Time magazine cover story about Rauschenberg, Mr. Beebe saw “The Diver” in “Pull, 1974,” from Rauschenberg’s “Hoarfrost” series. He contacted his lawyer, and Rauschenberg settled out of court.

By 1979 the mounting legal issues over his use of found images prompted him to buy a new camera and start photographing again. “I’ve never stopped being a photographer,” he told an interviewer in 1981. One picture from this period shows a director’s chair in his Florida studio on Captiva Island. Draped over the back is a Mona Lisa print on fabric; clothing hangs over the arms; a folded newspaper lies on the seat; light switches are mounted on the wall, a small grid of electric plugs near the floor. The picture is constructed with the geometry of a Combine, objects composed with the “random order” Rauschenberg considered his aesthetic.

In 1987 Rauschenberg told Ms. Rose, “I am a photographer, still.”

He often talked about what he learned from Archer at Black Mountain, said Laurence Getford, an assistant in Rauschenberg’s Captiva studio in his later years. When together they looked through his pictures to choose ones to incorporate in photo collages, Rauschenberg dismissed well-composed shots. “One gets as much information as a witness of activity from a fleeting glance, like a quick look, sometimes in motion, as one does staring at the subject,” he said. “Because even if you remain stationary, your mind wanders, and it’s that kind of activity that I would like to get into the photograph.”

Walter Hopps, the renowned museum curator who died in 2005, believed that photography was an essential device for Rauschenberg’s melding of imagery throughout his career. “Without photography,” he wrote, “much of Rauschenberg’s oeuvre would scarcely exist.”

Robert Rauschenberg as Photographer

By Elissa CurtisNovember 2, 2011

The artist Robert Rauschenberg was always interested in bringing a full range of media to his artworks—he’s most famous, after all, for his “Combines” of 1954-1964, works that, as the name suggests, combined non-traditional materials from various disciplines, such as painting and sculpture. But just how much of an interest Rauschenberg had in photography, and its importance in his work, is made clear in a new book from D.A.P./Schirmer/Mosel, “Robert Rauschenberg: Photographs 1949-1962.”

“It is surprising how little attention Rauschenberg’s photographs have gotten, considering it was his primary interest,” said David White, Rauschenberg’s curator from 1980 until the artist’s death in 2008, and co-editor of the book. Under the tutelage of figures such as Hazel Larsen Archer and Aaron Siskind at Black Mountain College in North Carolina in the late forties, Rauschenberg “wasn’t sure if he wanted to pursue a career as a photographer or painter, and in a way ended up doing both,” White told me. But it was his paintings that always took precedence in exhibitions, and which garnered the most attention. As a result, “the photographs fell by the wayside,” White surmised. “Not that he ever saw it that way.”

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten