The work of the American photographer Stephen Shore (b. 1947, New York City) has shaped contemporary photography and inspired generations of photographers. He has never stopped exploring the boundaries of photography, and has selected subjects that were not seen as obviously photogenic. He has effortlessly switched back and forth between black and white and colour, and has experimented with a wide variety of cameras and every possible format. This exhibition covers the period 1960–2016 and shows important turning points in his career.

In the early 1970s Stephen Shore roamed across his homeland, America, and photographed things in the same way he looked at them: factually, and with a style apparently devoid of artistic pretension. He photographed unspectacular subjects like motel interiors, a pancake breakfast, car parks, and traffic intersections. He did not shrink from the use of harsh flash, and he photographed in colour, something that celebrities such as Walker Evans (Shore’s great example) had deemed vulgar and which until then had been used only in advertising.

Stephen Shore and Ivy Nicholson, 1966

‘The quiet, shy teenage Stephen Shore, discreetly taking his photos at the Factory after school, alongside the glamorous model Ivy Nicholson who had recently arrived in New York from Europe… I remember Stephen didn’t like this photo because he thought he looked like a gangster.’Shore started with photography at a young age. At age eight he received his first camera, at fourteen he sold his first three photographs to the MoMA, and at 24 he was exhibited (as its second-ever living photographer) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Between 1965 and 1967 he was a regular at Andy Warhol’s Factory, and documented the artist and his entourage during their day-to-day activities.

After a brief period spent experimenting with conceptual photography, over the following two decades Shore devoted himself exclusively to colour photography. A grant from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation funded more travels throughout America. This colour-photo crusade resulted in several extensive series. American Surfaces (1972–1973) consists of hundreds of snapshots that together form a visual diary of his travels. Shore had photographed everything: what he ate, where he slept, and who he met. The series was first exhibited in the LIGHT Gallery in 1972. The garishly-lit snapshots were rather at odds with the work of established photographers like André Kertész and Paul Strand, both masters of black and white composition, and the work was initially given a very critical reception.

Shore was always exploring the limits of the medium and of his own technical skills. He started with a 35mm Rollei, occasionally switching to a Mick-o-Matic, a camera shaped like a Mickey Mouse head. For the series Uncommon Places (1973–1981) and Landscapes (1984–1988) he moved to 4×5” and 8×10” film. The unwieldiness of the view camera and tripod that these formats required made it difficult for him to take snapshots, but Shore used them anyway as he wanted to record more detail. This resulted in serene compositions of the North American urban landscape: diners, street corners and shop windows.

For recent colour work Shore has travelled to the Ukraine to document the lives of Holocaust survivors. For him, Ukraine (2012–2013) explores an unusually charged subject. The most recent work in the exhibition is Winslow Arizona (2013), made at the invitation of the artist Doug Aitken. In Aitken’s ‘nomadic happening’ Station to Station, a train made a three-week journey from New York to San Francisco, with artists and performers organizing an event at each stop. On one of these stops Shore spent the day photographing Winslow, a location that has regularly appeared in his work ever since the 1970s. These photographs were screened at a drive-in, unedited, and in the order in which he printed them. This series is now being shown in the Netherlands for the first time.

In 1970, Stephen Shore’s work was exhibited for the first time in the Netherlands, as part of a group show. After a retrospective in 1997, once again his work is being exhibited in the Netherlands. This large and long-awaited retrospective contains over 200 works and will occupy all twelve of the museum’s galleries. Besides photographs the exhibition will include his postcards, video work and (scrap)books, and his Instagram account will also be projected on the museum wall. The exhibition is an initiative of the Fundación MAPFRE and was curated by Marta Dahó. After being shown at Fundación MAPFRE, Les Rencontres d’Arles and C/O Berlin, the exhibition will now be on show at Huis Marseille.

Is this really Stephen Shore’s first retrospective?

Madrid show takes in motels, postcards, high concepts and print-on-demand experiments

Stephen Shore, West Ninth Avenue, Amarillo, Texas, October 2, 1974. From the series Uncommon Places.

All works ©Stephen Shore. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York

The photographer Stephen Shore had his first major exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1971. This was only the second show by a living photographer at the Met. Did Shore really have to wait a further forty-three years for his first major retrospective?

That’s the claim Fundación Mapfre is making upon opening its Shore retrospective in Madrid. The exhibition, which welcomed visitors last Friday and runs until 23 November, is an incredible career overview, but is it really the first? In all honesty, the American photographer has been the subject of earlier retrospective solo shows, such as Stephen Shore: Photographs, 1973-1993, which toured Europe in the late nineties.

Stephen Shore, self portrait, 1976.

Yet single period, tightly curated Shore exhibitions are a more common sight. The artist, who began shooting in the 1950s, had his first photographs acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in 1962, and started to document Warhol’s Factory in 1965, has always been meticulous in his career progression, with very clear delineation between the various periods of his work. Perhaps gallerists preferred to present these exquisitely conceived projects, rather than jumble the works together.

Stephen Shore, July 22, 1969

Nevertheless, Fundación Mapfre’s large-scale 320-photograph exhibition is a remarkable examination of Shore’s life and work. The show opens with his very early exercises in Walker Evans-style documentary work, and his nascent conceptual projects, such as July 22, 1969, wherein Shore shot his friend Doug Marsh every half hourn during a seemingly unremarkable day in Amarillo, Texas.

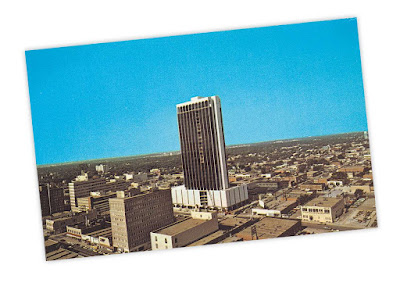

Stephen Shore, American National Bank Building, 1971. From the series Greetings from Amarillo-Tall in Texas.

This is followed by his best-known, early colour experiments from the 1970s, including his postcard project, for which the photographer produced a series of anodyne landscapes and printed them up into conventional, commercial postcards. There’s also American Surfaces, a photo-diary of Shore's road trip across America which, rather than capturing than key sights and experiences, features disconcertingly ordinary shots of his daily meals, hotel rooms and checks.

Stephen Shore, Trail’s End Restaurant, Kanab, Utah, August 10, 1973. From the series Uncommon Places

Shore’s beautiful and somewhat overlooked landscape photographs from the 1980s are on display here too. These views of the Texan and Scottish wilderness are quite unlike the poppier shots of the earlier decade, and foreshadow some of his work in Israel, a decade or two later.

Stephen Shore, Brewster County, Texas, 1987

The Mapfre exhibition also takes in an interesting return to monochrome film in the 1990s, with a series of sharp black-and-white studies. Shore’s 2003 experiments with iPhoto print-on-demand publishing are covered too. A little over a decade ago, the photographer began to a series of small books, shot and conceived in a single day. You may be interested to know Phaidon collected these together in our 2012 anthology, The Book of Books.

Finally the exhibition rounds off with Shore’s more recent projects, such as his work depicting holocaust survivors in the Ukraine and his participation with Doug Aitken’s Station-to-Station event last year. For Aitken’s train-based art festival, Shore spent a days shooting the railroad town of Winslow, Arizona.

Stephen Shore, Musya Vainshteyn’s Home, Nemirov, Ukraine, October 16, 2013

Any fine artist would be proud of so varied and distinct a body of work. Yet it’s all the more impressive given Shore’s medium; photography was only accepted as being of sufficient artistic merit a few decades ago. Shore’s retrospective proves just how expansive and capacious a tool photography can be in the hands of an artist, from the very moment MoMA and co were willing to hang photographic prints on their walls.

Stephen Shore, Shnuriv Lis, Ukraine, October 16, 2013

For more on the show go here. For greater insight into Stephen Shore’s American Surfaces consider our book; for more on the postcards get this Road Trip Journal; for more on his print-on-demand experiments try The Book of Books; for a career overview, buy this monograph, and for a more general view, browse through our other books and collectors edition prints, here. You can even buy a rare copy of July 22 1969, here.

5 Things Stephen Shore Can Teach You About Street Photography by Eric Kim

Stephen Shore

(All images in this article are copyrighted by Stephen Shore)

While in Amsterdam I checked out the FOAM photography museum and picked up a book on Stephen Shore. For those of you who may not know, he is one of the early color pioneers in photography in America. Although his style is classified more as documentary and urban landscape, I think there is a lot of things we can learn from him as street photographers. If you are interested in learning more about color and street photography, read on!

1. Create A Visual Diary

(Copyright: Stephen Shore)

Street photography doesn’t only need to be shots of other people walking about on the streets. It can be a deep self-reflection of yourself – and how you see society through your photographs.

When Stephen Shore worked on his “American Surfaces” project, he took a road trip across America and took photos of the following things:

People he met

Meals he ate

Beds he slept in

Art on walls

Store windows

Residential architecture

Television sets watched

He also took all of these photos on a cheap Rollei 35mm camera, and traveled all across America.

Through these images you don’t see the images as they are, but as a reflection of how Stephen Shore saw the places he visited. For example, when he took a photograph of four chicken bones (he just ate at a diner) he did so because he thought the food was awful, and couldn’t understand why anyone would cook or eat that kind of stuff in America.

Therefore when you’re out shooting street photography, try to add your own personality and view of the world in your shots. Don’t feel that all of your shots have to be of crazy-extraordinary “decisive moments – look for the “boring” and mundane things around you to capture. Think about how a series of images can create your own “visual diary”.

2. Shoot Color For Visual Accuracy And Realism

(Copyright: Stephen Shore)

In the book there was a quote by Peter Schjeldahl:

“Black and white can show how something is. Color adds how it is, imbued with temperatures and humidities of experience”.

Former curator of MOMA, John Szarkowski wrote eloquently on these jet as well saying:

“Most color photography, in short, has been either formless or pretty. In the first case the meanings of color have been ignored; in the second they have been at the expense of allusive meanings. While editing directly from life, photographers found it difficult to see simultaneously both the blue and the sky” – John Szarkowski 1976.

Therefore when it comes presenting your work, consider why you decide to present it in color vs black and white. Consider color as a way to see the world in a descriptive and “real” way, and black and white to see the world in a more conceptual and imaginary way (we don’t see the world in black and white).

I also recommend for people to go out shooting thinking in either black and white or color. This is because when you are shooting in the streets, you will see the world differently (depending on how you approach it).

For example, when I’m shooting in black and white film, I see the world as abstractions in terms of lines, shapes, reflections and shadows etc. However when shooting in color I see things like clothes, juxtaposition of colors, logos, etc.

3. Date Your Images

(Copyright: Stephen Shore)

We often look back at the old photos of Paris in the 1920s and feel nostalgia. We tell ourselves, “Man, the world was so much more interesting back then. Why can’t the world we live in be as interesting?”

However consider that people living in the 1920s didn’t find anything interesting about Paris the way we do. Sure in the old photos we see women wearing extravagant outfits and hats, and men with old-school suits. But back then, everyone wore that. It’s kinda like how nowadays when we see someone on their iPhone we think it’s boring. A hundred years from now, I’m sure people will find it fascinating (then they will probably have the iPhone 38s or something).

In his book shore mentions Specifically adding cars or telephone booths to his photos saying,

“I remember thinking that it’s important to put cars in photographs because they are like time seeds. And I learned this from looking at Evans”

So when you are out shooting on the streets, realize that a hundred years from now your photos will be a part of history. Don’t romanticize the past, think about today as tomorrow’s yesterday.

4. Experiment With Different Formats

(Copyright: Stephen Shore). A photograph he shot with an 8×10 view camera.

When Stephen shire was working on his “American Surfaces” project, he used 35mm small format film on a Rollei 35 camera, and took images as “purposeful snapshots“.

However for his next project he embarked on, “Uncommon Places” he decided to switch to a 8×10 large-format view camera (similar to what Ansel Adams used) for more clarity and detail in the urban landscapes he shot.

Also when shooting with his view camera, he could see exactly how his photos would look through the glass plate, which allowed him to create tighter, and better composed images.

Stephen Shore experimented two sides of the spectrum in terms of equipment (a tiny and compact 35mm camera vs a cumbersome view camera on a tripod). By shooting with different cameras, his approach to photographing his subjects changed.

Although I believe in the importance of staying consistent with equipment, I don’t want to restrict your creativity by experimenting. Therefore depending on what project you are working on, try to experiment with different cameras, formats, or equipment. If you shot film all your life, try using an iPhone. If you have only shot digital, try film.

5. Go Against The Grain

(Copyright: Stephen Shore)

When Shore was doing his photography projects With his 8×10 view camera, he was going against small or medium format shooters like Frank, Winogrand, Friedlander, and Arbus. But at the same time, he was going against the f64 group (Ansel Adams group) by shooting color.

Therefore don’t feel like you always have to fit under conventions. Shoot street photography with hipstamatic and add crazy filters if you want. If you like HDR, go ahead and do that.

Although I personally don’t agree with crazy effects or over-processing, once again make yourself happy and try to experiment. To be creative, it is necessary to break out of the typical “boundaries of photography”. However if you are going to break the boundaries in terms of how you present your images, do it consistently and purposefully. Don’t do it for the sake of doing it, but have a real reason why you want to try something differently.

Conclusion

Copyright: Stephen Shore

I feel some of the best insights we can get about street photography isn’t always by street photographers (by definition). Rather, gaining inspiration from other photographers similar to street photographers (and even completely opposite from street photographers) can help us become more creative, to break boundaries, as well as push the limits.

‘Ik wil de beste snapshots maken die er bestaan’

Interview Stephen Shore Tijdens zijn vele omzwervingen door Amerika legde fotograaf Stephen Shore het alledaagse leven vast in snapshots. De pionier van de kleurenfotografie wordt nu geëerd met een retrospectief in Huis Marseille.

Sandra Smallenburg

9 juni 2016

'Federal Highway 97 south of Klamath Falls, Oregon, 21 july 1973'

foto’s Stephen Shore. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York

Ze zijn er nog steeds, langs de eenzame highways in Amerikaanse staten als Utah, Wisconsin of Idaho. Shabby motels met bloemetjesspreien op de queensize bedden en ingelijste legpuzzels aan de schrootjeswanden. Diners waar de stapels pannenkoekjes worden geserveerd op formica tafels met papieren placemats waarop cowboys en indianen staan afgebeeld, of bijbelse psalmen.

De Amerikaanse fotograaf Stephen Shore (New York, 1947) legde ze vast in zijn legendarische series American Surfaces (1972-1973) en Uncommon Places (1973-1981). Toen al zagen de roadside motels en restaurants, veelal gebouwd in de jaren veertig en vijftig, er gedateerd uit. Wie de foto’s nu bekijkt, op Shores overzichtstentoonstelling in Huis Marseille, herkent de plekken direct. Dit zijn de stadjes waar films van David Lynch of de Coen Brothers zich zouden kunnen afspelen. Dit is de vergane glorie van smalltown Amerika.

'Beverly Boulevard at La Brea Avenue, Los Angeles, California, 21 june 1975'

Toen Shore ze begon vast te leggen, tijdens zijn zwerftochten door Amerika, werd fotografie nog maar nauwelijks gezien als kunstvorm. En kiekjes in kleur, zoals Shore ze maakte met zijn Rollei 35mm-camera, waren al helemaal not done. Kleur was vulgair. Echte foto’s, die van Paul Strand en Walker Evans bijvoorbeeld, waren zwart-wit. Shore liet zijn roadtripfoto’s gewoon afdrukken door Kodak, op klein formaat. Hij wilde snapshots maken die „volkomen authentiek” waren. ‘Snapshotness’, zo noemde Shore de stijl waarnaar hij op zoek was. Het is een spontane manier van werken die je later terugzag bij Martin Parr, Wolfgang Tillmans en Nan Goldin – fotografen die duidelijk schatplichtig zijn aan Shores pionierswerk.

„Snapshots hebben natuurlijk hun eigen beeldconventies”, zegt Stephen Shore, aan de telefoon vanuit zijn New Yorkse studio. „Ik heb altijd geprobeerd de beste snapshots te maken die er bestaan. Soms legt iemand namelijk iets vast in een snapshot wat heel direct en raak is. Ik zie dat ook gebeuren op ansichtkaarten. Dan heeft de fotograaf van zo’n ansicht het mandaat om te tonen hoe bijvoorbeeld een hoofdstraat in een klein dorp eruitziet, of hoe een motel eruitziet. Zo’n fotograaf is niet bezig met kunst maken. Daardoor hebben ansichtkaarten vaak diezelfde kwaliteit van directheid.”

Wat ik van Warhol leerde, was het belang van de serie

Stephen Shore: Retrospective. 10 juni t/m 4 sept in Huis Marseille, Keizersgracht 401, Amsterdam. Inl: huismarseille.nl

In Huis Marseille is een vroege serie te zien, Greetings From Amarillo (1971), die je een ode aan de ansichtkaart zou kunnen noemen. Tegen de strakblauwe Texaanse lucht legde Shore de belangrijkste gebouwen van Amarillo vast: de bank, het ziekenhuis, het gerechtsgebouw, Doug’s Bar BQ. De beelden hebben iets aandoenlijks, omdat de gebouwen niet bepaald van toeristisch belang zijn, maar nu toch maar mooi worden uitgelicht.

'Trails End Restaurant, Kanab, Utah, 10 August 1973'

Shore: „Een andere serie uit die tijd heette Mick-O-Matics, waarvoor ik een plastic camera gebruikte in de vorm van het hoofd van Mickey Mouse. Die twee series leidden uiteindelijk tot American Surfaces. Ik wilde met die kleurensnapshots doorgaan, maar dan wel met een betere camera. Om mezelf te trainen in het kijken heb ik een tijdlang op bijna ieder moment van de dag een soort ‘screenshot’ gemaakt van mijn blikveld. Dan was ik me heel bewust van wat ik zag en vroeg ik me af: als ik een foto zou maken van wat ik nu beleef, hoe zou die er dan uitzien? Dat werd het model van hoe ik wilde fotograferen: naturel. Ik wilde foto’s maken die voelden als kijken.”

American Surfaces bestaat uit tientallen kleinbeeldfoto’s die samen een intiem inkijkje geven van ‘life on the road’. Een beeldend dagboek is het, met foto’s van de maaltijden die hij at, de bedden waarin hij sliep, de mensen die hij tegenkwam. ‘Vernacular photography’ wordt die manier van werken wel genoemd: foto’s die de schoonheid van het alledaagse leven tonen en die eruitzien alsof je ze zelf, als amateur, ook gemaakt zou kunnen hebben. Wie langs Shores beelden in Huis Marseille loopt, ziet geen architectonische hoogtepunten of spectaculaire landschappen. Die toeristische blik probeert hij zoveel mogelijk te vermijden. Hij heeft oog voor de ‘nonplekken’: de anonieme parkeerplaatsen en de achterafsteegjes. De gebouwen die zijn neergezet zonder dat er een welstandscommissie aan te pas is gekomen.

Hij vertelt dat hij zichzelf een vreemdeling voelde in zijn eigen land, een ontdekkingsreiziger. „Ik kleedde me ook zo, in overalls en outdoor kleding. Ik woonde in New York, en afgezien van wat kustplaatsen had ik nog niets van Amerika gezien. Vanuit New York keek je toch meer richting het oosten, naar Europa, dan naar het Amerikaanse westen. In die zin voelde ik me verwant met fotografen als Henri Cartier-Bresson en Robert Frank en met schrijvers als Jack Kerouac en Vladimir Nabokov, die in de late jaren veertig ook roadtrips maakten door Amerika. Wat al die mannen gemeen hadden, was dat ze vreemdelingen waren. Ze bekeken Amerika met de ogen van de buitenstaander.”

Genadeloos licht

Building of the American National Bank, 1971. Uit de serie ‘Greetings from Amarillo-Tall in Texas’.

Kenmerkend voor de foto’s uit die beginjaren zijn de felle kleuren en de harde schaduwen. Neonreclames die fel afsteken tegen blauwe luchten, zwembadwater dat pijn doet aan je ogen. „Voor mij was het Amerikaanse westen echt exotisch”, zegt Shore. „De immense ruimte die je er had, het genadeloze licht. Het was de tijd dat aan de rand van ieder stadje een commerciële strip werd aangelegd. De eerste restaurants van McDonald’s gingen open. Langs de weg stonden borden met hoeveel hamburgers er die dag verkocht waren. Ik was gefascineerd door het landschap en de autocultuur, maar vooral ook door de mensen en hoe die met elkaar omgingen. Het ritme van het leven. Er werd veel meer rondgehangen op straat dan in New York, waar iedereen altijd maar druk was.”

Een van de mooiste foto’s op de tentoonstelling toont een billboard langs de US 97 in Oregon, met daarop een besneeuwde bergtop. Voorgrond en achtergrond lopen bijna naadloos in elkaar over, al is de echte lucht vele malen dramatischer dan de reproductie op het billboard. „Die foto is nog steeds heel populair. Voor mij was dat beeld haast té voor de hand liggend. Maar iedereen reed er gewoon ongezien langs. Mijn oog valt blijkbaar juist op de dingen waar anderen aan voorbij lopen. Ik heb ook een foto van een doodgewone schemerlamp in een motelkamer. Dat is geen onderwerp dat roept om een foto. Maar ik zag daarin de schoonheid van de alledaagse wereld.”

Factory als leerschool

De ambitie om fotograaf te worden, had Shore al op jonge leeftijd. Hij was zes toen hij zijn eerste fotorolletjes ontwikkelde en veertien toen hij de fotografieconservator van het MoMA – fotograaf Edward Steichen – benaderde of hij zijn portfolio kon komen laten zien. Dat leidde meteen tot de aankoop van drie van zijn afdrukken. Op zijn 23ste had Shore zijn eerste tentoonstelling in het Metropolitan Museum. Hij was pas de tweede levende fotograaf die dat was gelukt.

En dat voor een fotograaf die nooit een opleiding had genoten. Zijn leerschool, vertelt Shore, was Andy Warhols atelier The Factory in New York, waar hij tussen 1965 en 1967 bijna dagelijks rondhing en waar hij assisteerde bij de filmproducties. „Mijn leeftijdgenoten gingen naar de universiteit, ik begon als lichttechnicus te werken in The Factory. Op dat moment had ik er natuurlijk geen benul van hoe die periode vijftig jaar later beschouwd zou worden als een gouden periode, de hoogtijdagen van de pop-art. Het is anders om er middenin te staan en het mee te maken. Die mensen waren mijn vrienden. Maar ik had wel door dat The Factory een spannende plek was, waar interessante dingen gebeurden.”

Als achttienjarige was Shore diep onder de indruk van Warhol. Hij bestudeerde de kunstenaar tijdens zijn werkzaamheden en praatte met hem over kunst. „Mensen denken bij The Factory altijd aan de feesten, en die waren er ook wel. Als Andy naar een cocktailparty of een opening ging, wist je dat hij iedereen meenam die op dat moment in The Factory rondhing. Er lagen altijd mensen op de bank te wachten tot ze mee konden. Maar Andy kwam ook iedere middag naar The Factory om te werken. En dan bekeek ik hem. Ik zag een kunstenaar die voortdurend esthetische beslissingen aan het nemen was, iedere dag weer. Ik leerde zoals een leerling-kunstenaar het vak zou leren, door in de nabijheid van een grote kunstenaar te verkeren.

„Wat ik van hem meekreeg, was het belang van de serie. En allebei hadden we een grote liefde voor de hedendaagse populaire cultuur. Waar hij en ik elkaar aanvoelden, was dat we die beiden van een zekere afstand bekeken. Warhol was een observator, zoals ik als fotograaf ook een observator ben.”

Een andere inspirator was de Amerikaanse kunstenaar Ed Ruscha, die eind jaren zestig fotografie gebruikte voor zijn conceptuele reeksen. „Vooral zijn boek Every building on the Sunset Strip (1966), waarin hij foto’s van alle gebouwen op Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles aan elkaar had geplakt, maakte diepe indruk. Sinds die tijd ben ik gefascineerd door kunstenaarsboeken.”

Een verrassend onderdeel van de tentoonstelling is de serie ‘print-on-demand’-fotoboeken waarmee Shore in 2003 begonnen is: zelfgemaakte fotoboeken die steeds één dag in beeld brengen. Hij maakte er tot nu toe 83. Geen fotoboeken in hoge oplage, maar één uniek exemplaar. Shore: „Nu is het heel gemakkelijk geworden om je eigen fotoboeken te maken en te laten printen bij de plaatselijke drogisterij. Als je een fotoboek maakt, kun je natuurlijk kiezen voor 100 van je beste foto’s, dan maak je achteraf echt een overzicht. Maar je kunt ook een serie maken met het boek in je achterhoofd. Dat is wat ik gedaan heb. Ik ga eropuit met een idee in mijn hoofd, ’s avonds upload ik de foto’s en drie dagen later levert Fed-Ex een fotoboek bij me af.”

Nog steeds vindt Shore inspiratie in de meest eenvoudige dingen. „Ik fotografeer bijvoorbeeld veel in mijn tuin. Ik vind alle periodes mooi, ook het verval. Ik houd juist van de dorre periodes, wanneer de planten uitgedroogd zijn. Het zijn niet alleen de mooiste momenten van bloei die interessant zijn.”

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten