donderdag 13 december 2012

Final Destination the forest of Aokigahara Mount Fuji Pieter ten Hoopen Photojournalism Photography

Geologist Azusa Hayano (66) grabs a rope that is tied right next to the trail winding through the dense forest which lies in the shadow of Mount Fuji. This Forest is so dense with vegetation, that it is known for being almost impossible to navigate through. Even a GPS or a compass wouldn’t help a lost visitor. This is the reason why the forest of Aokigahara as been elected by so many as their final destination: every year, hundreds of people choose to come and die here. In 1960, Seicho Matsumoto wrote a novel called “Tower of wave", in which a loving couple commits suicide in this particular forest. This book triggered a wave of suicides in Aokigahara forest with people travelling from afar to take their lives here. The forest is also described in another book by author Wataru Tsurumi, entitled “The complete manual of suicide”, which gives the reader all the different possible methods to commit suicide. The book became a best seller in Japan and has been found next to many of bodies in the woods. Wataru Tsurumi describes Aokigahara forest as the perfect place to die. In the book the author explains how to drive to this forest, and which part of the forest is best never to be found. The forest is also called the sea of trees (or “Yukai “) by the locals, because of its dense vegetation. It stands on the remains of the last volcanic eruption that occurred 864 years ago, over a surface of more than 3500 hectares. Those who get into the woods often tie a rope next to the trail and then follow the rope along a few hundred meters. The ropes are usually painted in white and blue and some parts of the forest are completely filled with them. At the end of the ropes, pills, food, clothing, diaries, are often found. A few weeks before our arrival the forest had been cleared of all bodies, which is done once a year, right before the holiday season begins. How weird this place now may be, it is a great tourist attraction. Lees verder ...

Pieter ten Hoopen is an experienced and internationally acclaimed photographer based in Stockholm, Sweden. Transitioning between editorial work, personal projects and commercial assignments, ha has a wide range of returning customers as New York Times magazine, Le monde, Expressen, Dagens Naeringsliv.

Final Destination the forest of Aokigahara Mount Fuji Pieter ten Hoopen Photojournalism Photography

Geologist Azusa Hayano (66) grabs a rope that is tied right next to the trail winding through the dense forest which lies in the shadow of Mount Fuji. This Forest is so dense with vegetation, that it is known for being almost impossible to navigate through. Even a GPS or a compass wouldn’t help a lost visitor. This is the reason why the forest of Aokigahara as been elected by so many as their final destination: every year, hundreds of people choose to come and die here. In 1960, Seicho Matsumoto wrote a novel called “Tower of wave", in which a loving couple commits suicide in this particular forest. This book triggered a wave of suicides in Aokigahara forest with people travelling from afar to take their lives here. The forest is also described in another book by author Wataru Tsurumi, entitled “The complete manual of suicide”, which gives the reader all the different possible methods to commit suicide. The book became a best seller in Japan and has been found next to many of bodies in the woods. Wataru Tsurumi describes Aokigahara forest as the perfect place to die. In the book the author explains how to drive to this forest, and which part of the forest is best never to be found. The forest is also called the sea of trees (or “Yukai “) by the locals, because of its dense vegetation. It stands on the remains of the last volcanic eruption that occurred 864 years ago, over a surface of more than 3500 hectares. Those who get into the woods often tie a rope next to the trail and then follow the rope along a few hundred meters. The ropes are usually painted in white and blue and some parts of the forest are completely filled with them. At the end of the ropes, pills, food, clothing, diaries, are often found. A few weeks before our arrival the forest had been cleared of all bodies, which is done once a year, right before the holiday season begins. How weird this place now may be, it is a great tourist attraction. Lees verder ...

Pieter ten Hoopen is an experienced and internationally acclaimed photographer based in Stockholm, Sweden. Transitioning between editorial work, personal projects and commercial assignments, ha has a wide range of returning customers as New York Times magazine, Le monde, Expressen, Dagens Naeringsliv.

woensdag 12 december 2012

Always the Same, Always Different When I Open My Eyes Wout Berger Photography

Wout Berger - When I Open My Eyes

- Paperback: 130 pages

- Publisher: Fotohof (June 1, 2012)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 3902675756

- ISBN-13: 978-3902675750

In the morning, when I open my eyes, the first thing I look at is the IJsselmeer and the light: always the same, always different.

For over thirty-five years, I've been a photographer.

For over thirty-five years, I've been living on the IJsselmeer.

When I open my eyes in the morning, the first thing I see is the IJsselmeer.

Sometimes I take a picture of it, but really seeing it is something else.

Not until a friend said to me, "You live in your subject matter," did the penny drop.

I placed a tripod at a fixed spot in front of the bedroom window and began to look.

At first you're grateful for every sailboat that comes along. Every intense sky: a photograph.

But before long you start keeping every distraction out of the picture. It's what anyone open to the subject matter ends up doing.

I no longer photograph sailboats. Nor do I photograph birds, or people.

I do take pictures of little waves, patches of fog, rain and clouds. These, too, can be distracting; but their forms are almost always amorphous, transparent, wet. They scarcely have any color of their own, but they take on the color of light cast on them and then reflect that.

Sixty photographs in all: together they make up my IJsselmeer. No one photograph is any nicer than another. If you start looking at photographs that way, you get lost in aesthetics. I'm not after aesthetics. I want to photograph wind, light—elements that we know only by their manifestations. You don't see the wind; you see a wave. You don't see light; you see the cloud that catches light. And yet I still want to capture wind and light—by looking, time and again, at the same subject situated, time and again, at the same coordinates.

Differences among the images can be small. Between two photographs that seem nearly identical, there might be a month-long lapse of time. Meanwhile, the subject remains the same. At least that's what you think. Imperceptibly, the subject begins to change. While it was initially all about the body of water, the horizon, the sun, the clouds, the wave, unnoticeably the subject becomes the differences among the photographs. The transitions. That's where I hope to touch on the untouchable. Hopeless of course. But it's worth a try.When I open my eyes in the morning, the first thing I see is the IJsselmeer.

Sometimes I take a picture of it, but really seeing it is something else.

Not until a friend said to me, "You live in your subject matter," did the penny drop.

I placed a tripod at a fixed spot in front of the bedroom window and began to look.

At first you're grateful for every sailboat that comes along. Every intense sky: a photograph.

But before long you start keeping every distraction out of the picture. It's what anyone open to the subject matter ends up doing.

I no longer photograph sailboats. Nor do I photograph birds, or people.

I do take pictures of little waves, patches of fog, rain and clouds. These, too, can be distracting; but their forms are almost always amorphous, transparent, wet. They scarcely have any color of their own, but they take on the color of light cast on them and then reflect that.

Sixty photographs in all: together they make up my IJsselmeer. No one photograph is any nicer than another. If you start looking at photographs that way, you get lost in aesthetics. I'm not after aesthetics. I want to photograph wind, light—elements that we know only by their manifestations. You don't see the wind; you see a wave. You don't see light; you see the cloud that catches light. And yet I still want to capture wind and light—by looking, time and again, at the same subject situated, time and again, at the same coordinates.

See also Poisoned Landscape by Wout Berger Online Photobook Photography ...

Giflandschappen, Wout Bergers boek uit 1992 met opnames van vervuilde gronden in Nederland, is een macabere dans van vorm en inhoud. Hoe kunnen plekken die zo zwaar vergiftigd zijn er op foto’s idyllisch uitzien? Hoe kan lelijk zo mooi zijn?

Twintig jaar later komt When I open my eyes uit en ook daar staan vorm en inhoud in een verrassend verband. De foto’s staan aflopend op de rechterpagina’s van het boek. Tot 1 januari volgend jaar zijn ze in groot formaat te bewonderen in een serene zaal in Museum De Pont.

Zodra je een van de foto’s los van de andere bekijkt, wordt ie mooi. Te mooi. Water-horizon-lucht, iedere foto scheert rakelings langs het cliché van de zonsondergang. Daar gaat When I open my eyes niet over.

Het is in de hoeveelheid van opnames, allemaal met ander licht, andere wolkenlucht, andere rimpels op het water, dat je het begint te zien. When I open my eyes is een speurtocht naar de eindeloze verschijningsvormen van steeds weer hetzelfde stukje water, gezien vanuit dezelfde zolderraam, zijn zolderraam. Dat is de schoonheid van de tentoonstelling en van het boek. Die staalkaart, die bijna meteorologische verzameling, die encyclopedie van het Nederlandse uitzicht. Lees verder ...

vrijdag 7 december 2012

Bintphotobooks selection of Notable photoBooks 2012

...A PHOTOBOOK IS AN AUTONOMOUS ART FORM, COMPARABLE WITH A PIECE OF SCULPTURE, A PLAY OR A FILM. THE PHOTOGRAPHS LOSE THEIR OWN PHOTOGRAPHIC CHARACTER AS THINGS 'IN THEMSELVES' AND BECOME PARTS, TRANSLATED INTO PRINTING INK, OF A DRAMATIC EVENT CALLED A BOOK... - DUTCH PHOTOGRAPHY CRITIC RALPH PRINS

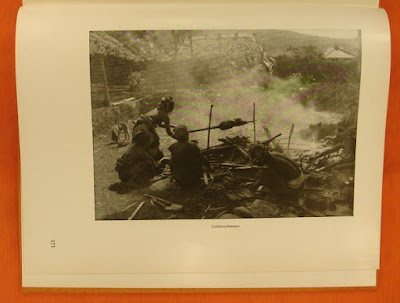

Lebensmittel - Food

door Michael Schmidt , see also ...

Ed Van Der Elsken - Look. Ed!

door Jhim Lamoree E.a.

Krass Clement: Drum: Books on Books No. 16

door Rune Gade, Jeffrey Ladd, Krass Clement

Nobuyoshi Araki: The Banquet: Books on Books No. 15

door Nobuyoshi Araki, Ivan Vartanian, Jeffrey Ladd

Keld Helmer-Petersen: 122 Colour Photographs: Books on Books No. 14

door Mette Sandbye, Jeffrey Ladd, Keld Helmer-Petersen

Ed van der Elsken: Sweet Life: Books on Books No. 13

door Frits Gierstberg, Jeffrey Ladd, Ed van der Elsken , see also ...

Wout Berger

When I Open My Eyes , see also ...

Naked

door Rimaldas Viksraitis, design Herman van Bostelen editor Rob Knijn

Autopsie, Band 1: Deutschsprachige Fotobücher 1918 bis 1945

door Manfred Heiting, Roland Jaeger , see also ...

Josef Koudelka - Lime (French Edition)

Photographs of the Netherlands East Indies at the Tropenmuseum

door Janneke van Dijk, Rob Jongmans, Anouk Mansfeld, Steven Vink, Pim Westerkamp

(based on a true story)

door David Alan Harvey , see also ...

Touch

door Peter Dekens, design: Rob van Hoesel , see also ...

Men at work

door Thijs Heslenfeld

Report #5

door Theo Niekus, design Joseph Plateau

Enduring Srebrenica

door Claudia Heinermann, Jan Pronk Sonya Winterberg

The Netherlands - Off the shelf / Nederland - Uit voorraad leverbaar

door Hans van der Meer, Design: Kummer&Herrman , see also ...

Stay Cool

door RJ Shaughnessy

100 photos de Martin Parr pour la liberté de la presse

door Martin Parr

Photo Express Tokyo

door KEIZO KITAJIMA

Het Nederlandse fotoboek

door Rik Suermondt Frits Gierstberg, Flip Bool Auteurs: Tamara Berghmans, Patricia Börger, Martijn van den Broek, Karen Duking, Frits Gierstberg, Karin Krijgsman, Claudia Küssel, Pieter van Leeuwen, Pim Milo, Mirelle Thijsen, Mireille de Putter, Max van Rooy, Bart Sorgedrager, Rik Suermondt , see also ...

Greetings from Jakarta: Postcards of a Capital 1900-1950

door Scott Merrillees

maandag 3 december 2012

Bali Volk Land Tanze Feste Tempel Gregor Krause Deutschsprachige Fotobücher 1918-1945

KRAUSE, GREGOR, - Bali. Volk-land. Tanze. Feste. Tempel.

Georg Muller, 1926. Third Edition. Original orange cloth.

Deutschsprachige Fotobücher 1918-1945, thematisch geordnet

Autopsie. Deutschsprachige Fotobücher 1918-1945. Band 1. / Herausgeber: Manfred HEITING, Roland Jaeger. Mit Beiträgen von Ute Brüning [u.a.]. – Göttingen: Steidl 2012. – 4°. 516 S. mit Farbabbildungen. Pappband illustriert.

Band 2 erscheint 2013. Zusätzlich dazu werden alle Photobücher mit detaillierten bibliographischen Angaben und Abbildungen von Schutzumschlag und Einband von einer im Aufbau befindlichen Internet-Datenbank abrufbar sein (siehe weiter unten).

Die alte Bali-Fotos des Gregor Krause

Vermeintlich "objektive" Bilder im Spannungsfeld zwischen Ethnofotografie und Voyerismus

Dr. phil. Rainer Stamm, Kunstwissenschaftler im Fachbereich Design - Kunst- und Musikpädagogik - Druck

Gregor Krause/Karl With: "Bali", Hagen, 2. Aufl. 1922. Bucheinband mit Banderole

Als visuelle Erweiterung des Folkwang-Museums mit fotografischen Mitteln erschienen im Folkwang-Verlag seit 1920 die Buchreihen „Geist, Kunst und Leben Asiens“ und „Kulturen der Erde“, deren erfolgreichster Titel das von Karl With herausgegebene zweibändige ‘Bali’-Werk war. Gregor Krause war in den Jahren 1912-1914 als Arzt auf der Insel des indonesischen Archipels gewesen und hatte von dort rund 4000 fotografische Aufnahmen mitgebracht. In Absprache mit Krause hatte With rund vierhundert Aufnahmen ausgewählt und in zwei Bänden veröffentlicht. Dem durch den Schock des Ersten Weltkrieges erschütterten Europäer wird Bali hierin als ‘glückliche Insel’ vorgeführt, als Land vor dem Sündenfall.

Den kulturpessimistischen Furor vor dem ‘Untergang des Abendlandes’ mögen die Bilder und Berichte aus Bali nur zu bestätigen; Krause und With führen als Gegenbild eine Welt glücklicher Ganzheit vor, in der die Natur „keine Grenzen, Klüfte und Bezirke“ kennt, Götter, Tiere, Pflanzen und Menschen in Einheit und Eintracht leben und das „Chaos zur Ordnung“ wird:1)

„Ich habe gesehen, wie kleine Knaben furchtlos auf urweltlich starken Karbuwenbüffeln galoppierten, vor denen unsere tapferen Soldaten schnell in die nächsten Bäume klommen. Ich sah, wie eine Herde Stiere, die rasend einem häßlich brummenden Automotor den Weg versperrten, durch die freundliche Zusprache eines balischen Mädchens sich von der Fruchtlosigkeit ihres Zornes überzeugen ließen;“ 2)

Einen Höhepunkt des paradiesischen Zustandes finden Krause und seine - wie With ausdrücklich hervorhebt - versteckte Kamera (!) in der vollendeten Schönheit der Menschen auf Bali respektive der Frauen; so schwärmt der Autor im Text, „die balischen Frauen sind schön, so schön wie eine Frau nur gedacht werden kann“3) und illustriert seine Feststellung mit zahlreichen Fotos, die nichts weiter vermitteln zu wollen scheinen, als diese These im Bild zu untermauern. Besonders auffällig ist dabei, daß der Autor allein in 36 fotografischen Aufnahmen nackte Frauen und Männer beim Baden in freier Natur zeigt. Mit dem Mythos von ungezwungener Körperlichkeit in einem Urzustand, die Schamhaftigkeit vermeintlich nicht kannte, bedient Krause dabei ein zeittypisches Klischee.

Gregor Krause: "Ältere Frau beim Baden" (oben) "Jüngling nach dem Bade sich sonnend" (unten) Bali, 192-14; diese Aufnahme zitiert Hans Peter Dürr in seinem Werk "Nacktheit und Scham"

Die vermeintlich ‘objektiven’ Bilder aus dem fernen Bali kamen den zivilisationskritischen Reformbestrebungen als Argumentationshilfe und Bestätigung gerade recht. Fritz Giese etwa zitiert Krauses Aufnahmen in seinem Standardwerk der Körperreform-bewegung „Körperseele. Gedanken über persönliche Gestaltung“ (1924). Der hier abgebildete „Naturvolkakt“ ist im Sinne zivilisationskritischer Argumentation mit der Bildlegende versehen: „Unschuldige - harmlose - selbstverständliche Natürlichkeit des die Nacktheit gewöhnten Primitiven“.4) - Daß freilich auch der sog. Primitive seine Nacktheit aufs Baden in der freien Natur beschränkt, wird dabei geflissentlich übersehen.

In seinem umfassenden Versuch zur Entlarvung jenes ‘Mythos vom Zivilisationsprozeß’, der vor der Folie des Kulturpessimismus den ‘nackten Wilden’ zum unverdorbenen Ur-Menschen ohne Scham und Tadel zu stilisieren versucht, hat Hans Peter Duerr 1988 auch mit dem Klischee ‘nackter Unschuld’ und ‘vollständiger Selbstverständlichkeit’ in den von Krause aufgenommenen Badeszenen aufgeräumt. Anhand zweier Bilder Krauses weist er nach, daß an der Bein- bzw. Handhaltung der Badenden ihre Schamhaftigkeit abzulesen ist; doch hierzu bedarf es eines weniger eurozentrischen Blicks, der aufnahmebereit ist, auch fremde Zeichen der Körpersprache zu dekodieren.5) Denn - mit Susan Sontag zu sprechen -: „Es ist immer etwas Räuberisches im Spiel, wenn man ein Foto macht. Wenn man Menschen fotografiert, tut man ihnen Gewalt an, weil man sie sieht wie sie sich selbst nie sehen, weil man Wissen über sie hat, das sie nie haben können. Menschen werden in Objekte verwandelt, die symbolisch besetzt werden können.“ 6)

Krauses Bali-Buch hatte in Text und Bild den Mythos von der Ursprünglichkeit der glücklichen Insel in die Welt gesetzt. In seiner Studie über Ethnofotografie als Mittel populärer Mythenbildung führt Werner Wolf den Boom des Bali-Tourismus zwischen den Weltkriegen direkt auf Krauses Bildwerk zurück.7) Schriftsteller, Künstler und Fotografen folgten dem Traum vom Paradies und setzten die Arbeit am Mythos ihrerseits fort. Hiervon zeugen die Berichte der Maler und Zeichner Robert Genin, Heinrich Heuser und Walter Spies ebenso wie das Südseebuch ‘Heitere Tage mit braunen Menschen’ (1930) des Reiseschriftstellers Richard Katz oder der 1937 erschienene Erfolgsroman ‘Liebe und Tod auf Bali’ von Vicky Baum. Dem Bali-Boom folgten ferner die Filmemacher Lola Kreutzberg und Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, der Ethnograph Hugo Adolf Bernatzik und die Fotografen E.O. Hoppé, Fritz Henle, Josef Breitenbach, Henri Cartier-Bresson und Gotthard Schuh, dessen Bildband über die ‘Inseln der Götter’ bis 1960 zwölf Auflagen und drei Übersetzungen erlebte.

1) Karl With, Bali und wir, in: Gregor Krause, Inssel Bali, 1, Bd., Hagen 1920, S. 14

2) Gregor Krause, Insel Bali, 1. Bd., Hagen 1920, S. 19

3) ebd., S. 32

4) Fritz Giese, Körperseele, Gedanken über persönliche Gestaltung, München, 2. Aufl. 1927, Abb. 88, S. 87

5) Hans Peter Dürr, Nacktheit und Scham. Der Mythos vom Zivilisationsprozeß, Bd. 1, Frankfurt/Main, 3. Aufl, 1988 S. 146 ff

6) Susan Sonntag; hier nach: Gerhard Theewen, Über die Reproduzierbarkeit der Schönheit fremder Frauen, in: Klaus g. Gaida (Hg.), Erdrandbewohnder, Köln 1995, S. 139

7) Werner Wolff, in: Thomas Theye (Hg.), Der geraubte Schatten. Die Photographie als ethnographisches Dokument, München 1989, S. 346.

Abonneren op:

Posts (Atom)