‘Banjir! Banjir!’(flood! flood!) is a cry often heard with increasing frequency in Jakarta. The city is sinking, the sea level is rising and heavy rainfall causes rivers, clogged by rubbish and silt to burst their banks. Since 2014 I have been documenting what it’s like to live in Sinking City Jakarta.These pictures are now bundled in a book.

The book is in two parts. In the first part five leading experts describe the situation in Jakarta. The second part is devoted to eight photo-reportages.

Banjir! Banjir!

Photographs by Cynthia Boll

Concept and design by Ben Krewinkel

Witteveen+Bos

ISBN: 9789490335106

195 pages

In the first week of April 2014, a Dutch delegation headed by the Minister for Infrastructure and the Environment, Melanie Schultz van Haegen, paid an official visit to Indonesia. The programme included the presentation of the National Capital Integrated Coastal Development Masterplan (NCICD). In the past two years, Witteveen+Bos has worked on this plan together with Grontmij and a number of other parties.

The masterplan presents solutions for a number of problems affecting the Indonesian capital Jakarta, including flooding, soil subsidence, an inadequate water supply system and poor water quality. The document combines the proposed solutions with an analysis of the expected economic and social benefits.

Flood protection and urban development

When a public call for tenders was issued in 2012, Witteveen+Bos sought collaboration with other parties. This resulted in a consortium that also includes Grontmij, KuiperCompagnons, Deltares, Ecorys and Triple-A. Our proposal is based on a two-phase approach: flood protection in the short term, and sustainable urban development in the long term. The Dutch government (Partners for Water) decided to award the contract to the aforementioned consortium. The project beneficiary is the Indonesian government.

Groundwater extraction

Every year, part of Jakarta is flooded. February 2014 was no exception: floods left some 300,000 residents homeless and resulted in dozens of casualties. The water flows into the city and simply cannot be drained off quickly enough. Soil subsidence due to groundwater extraction is a major cause of the flooding problems. In some places, the soil subsides by up to 17 cm per year. But subsidence is not the only cause for Jakarta’s water problems. No fewer than thirteen rivers flow from the volcanic hinterland into Jakarta Bay, and growing urbanisation upstream is exacerbating the problem.

Densely populated metropolis

In 2030, some 80 % of North Jakarta will be located below sea level. The masterplan calls for offshore flood protection measures in Jakarta Bay, the only area that still offers enough room for such measures in this densely populated metropolis. The coast needs to be reinforced as a temporary measure, and a new enclosure dam must be built in the bay. The dam can be financed through simultaneous large-scale land reclamation. Plans calls for a new waterfront shaped like the mythical Garuda bird, the national symbol of Indonesia. Realisation would require massive investment in one of the world’s largest hydraulic engineering projects.

Feasibility

The plan has been carefully assessed for its financial, technical, socio-economic and ecological feasibility. The costs of implementing the various measures are currently estimated at USD 10 to 40 billion. The accelerated construction of urban sewer systems and water treatment plants is a key aspect of the plan. This will prevent the development of a dreaded ‘black lagoon’ of sewage lapping at the city’s waterfront behind the new seawall.

Phased plan

Rapid construction of a complete enclosure dam between the eastern and western end of Jakarta Bay is logistically unfeasible. For instance, supplying enough soil would require more dredging vessels than are currently available in the entire world. The volume of soil needed to construct the western section is comparable to the volume required for the Tweede Maasvlakte land reclamation project near Rotterdam. Many factors will determine if and how this masterplan is to be implemented. Factors like the growth of the Indonesian economy, currently at an annual rate of + 5 to 6 %, or presidential elections. To tackle the problems in phases, a sound plan has been prepared.

Review: Jakarta, Mon Amour

Written by Ron Witton

source: Scott Merrilleessource: Scott Merrillees

Published:

Feb 22, 2016

I recently came across three books that trace, pictorially, the history of the development of Jakarta, from the earliest days of photography in the mid-nineteenth century through to 1980:

Browsing through the books brought back a kaleidoscope of memories.

It all began in early 1962 when, as a newly arrived 18-year-old, first-year student at Sydney University, I sat down in Fisher Library next to an Asian student. We got talking about what we were studying and I told him I was studying French and German. He told me his name was Albert Kwee and that he came from Indonesia. He said that although he was of Chinese descent, he did not speak Chinese as his family had lived in Indonesia for many generations and only spoke Indonesian, the national language. Curious, I asked him about the language. He wrote down a few sentences, showing me that it was written perfectly phonetically in Latin script, had a very simple, straightforward grammar in that its verbs did not conjugate and its nouns and adjectives did not decline. For someone who had struggled through high school with the grammatical idiosyncrasies of Latin, German and French, and the intimidating nature of French pronunciation, Indonesian seemed like a breath of fresh air.

Soon after, I found that Sydney University had a Department of Indonesian and Malayan Studies. I quickly enrolled, and in so doing determined the course of the rest of my life. Albert became a life-long friend, each of us being best man at our respective weddings. I ended up completing my bachelor, master and doctoral degrees in Indonesian studies, have often lectured on Indonesia, and still work as an Indonesian interpreter and translator.

Half way through my first year studies, I was so taken by Indonesian studies that I decided to buy a ticket on a Lloyd Triestino passenger liner to see the country for myself. This is how, in December 1962, I caught my first glimpse of Indonesia from the deck of a ship as it sailed into Tanjung Priok, Jakarta’s harbour. I still have the letters I wrote home to my family and upon reading them now, I am transported back. In the distance behind the city, there were mountains and on the wharf below, I could see Albert’s family holding up a sign saying ‘Kwee’ so that I could recognise them. As they drove me to their home, I was overwhelmed by the stifling heat and humidity, the kaleidoscopic impression of becaks (pedicab), cars, army lorries, buses, street vendors, people, people and people. They drove me to their suburban house on Jalan Mangga Besar Raya in Kota, the north district of the city.

Ron Witton in 1962 in the front yard of the Kwee family home on Jalan Mangga Besar Raya - Ron Witton

Jalan Mangga Besar Raya was a wonderful introduction to Indonesian urban life. There was the constant ‘tok-tok’ of bamboo sticks and ‘clang-clang’ of metal bells coming from the street as a steady stream of vendors walked, pedaled and rode past the front gate selling a multitude of products, ranging from every conceivable type of food delicacy to every household good one might possibly want. Up the street was Prinsen Park, to which families thronged to enjoy the rides, performances and recreational facilities that had existed since colonial times. At the other end of the street were the major thoroughfares of Jalan Hayam Wuruk and Jalan Gajah Mada, which were then still rather grand tree-lined boulevards.

Source - Scott Merrillees

I soon became immersed in the Jakarta of the early sixties. The Kwee family drove me around the city to see the newly built monuments to Sukarno’s vision of a modern Indonesia, Sarinah, Jakarta’s first department store (still under construction), the new Japanese-built Hotel Indonesia, and the new Russian-built Senayan sports complex for the Asian Games with the Gelora Bung Karno stadium.

En route to the south of the city to see the newly established satellite residential district of Kebayoran Baru they drove me over the new Swedish-built Semanggi (meaning ‘Cloverleaf’) Bridge:

Source - Scott Merrillees

As Scott Merrillees comments in JAKARTA: Portraits of a Capital 1950-1980, ‘In this post card we are looking across a recently completed and still very dusty Semanggi with the new Senayan stadium in the distance.’

I recall that driving south to Kebayoran Baru I could still see rice fields on either side of the road. It is only now that I realise I had a very privileged experience of a world that was soon to change forever. The city has grown from around three million when I arrived in 1962 to the current largely unmanageable population of over 10 million, and continues to grow inexorably. The Kwee’s house on Jalan Mangga Besar Raya is now long gone and the suburban atmosphere I experienced there has been replaced by hotels, nightclubs, brothels and shopping malls. Becaks and many other aspects of 1962 life have disappeared from Jakarta’s streets. I was still able to see many beautiful buildings from the colonial era, such as the charming Hotel des Indes, which had already been renamed Hotel Duta.

Source - Scott Merrillees

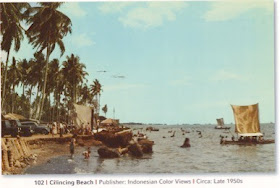

However, the hotel, like many other such historic buildings, was soon to be demolished to make way for a mall. One no longer sees mountains to the south of Jakarta as the pollution has drastically restricted visibility. One can no longer swim on the beach at Cilincing, near Tanjung Priok:

Source - Scott Merrillees

...and the rice fields I saw en route to Kebayoran Baru are also long gone.

I made two more visits to Jakarta in the 1960s, the second in late 1964 when I landed at Kemayoran, Jakarta’s former airport in the city’s east.

Source - Scott Merrillees

Over the decades since, I have made many more visits. Each time I have seen profound changes to the city, though underneath it all there is the old Jakarta I first experienced in 1962.

The three volumes by Scott Merrillees document, with a multitude of striking photos and postcards, lucidly discussed and contextualised, the way this city has changed from its earliest days as Batavia, Holland’s grand colonial outpost, to Jakarta, the modern city of today. The images accompanying this review are but a small taste of the fascinating sights captured in his three volumes. His commentary on each of the photos and postcards often draws one’s attention to details and features that would otherwise remain unnoticed. He also often links the image to his maps and to other images so that they become in effect a mosaic reflecting the city as a whole.

I am sure that for many who have ever lived in the city, one’s first inclination is to use the excellent indexes and maps in each volume to locate familiar places, relive the experience of having been there at a particular period, and to learn how they have changed over time. For example, I quickly found images of Mangga Besar, in colonial days named Prinsenlaan, and was amazed that the busy, crowded street of my memories had in former times been a quiet, grand tree-lined road:

Source - Scott Merrillees

I could even find an image of Prinsen Park, the amusement park down the road from the Kwee family home, whose name commemorates Mangga Besar’s colonial name of Prinsenlaan:

Source - Scott Merrillees

Prinsen Park was then re-named ‘Lokasari’ before finally succumbing to Mangga Besar’s less than family-friendly atmosphere of today. As has been the fate of many a Jakarta landmark, Lokasari was demolished to make way for yet another of Jakarta’s many malls.

The books have allowed me, through its images and maps, to explore where I have lived in later years, including Jalan Raya Radio Dalam in Kebayoran Baru and Jalan Yusuf Adiwinata in Menteng. There is also the enjoyment of looking at the changes in the locations of familiar institutions, such as the Australian Embassy’s former location on Jalan Thamrin before it was moved to Kuningan. I still recall that the embassy, located on the west side of Jalan Thamrin, also had offices on the east side. Due to the heavy and, for those on foot, life-threatening traffic of Jalan Thamrin, embassy regulations required diplomats and staff, if they wanted to go from the main building to the offices across the road, to take an embassy car north on Jalan Thamrin to a roundabout located some distance and then back south so as to enter the building on the east side. To return to the embassy, required a lengthy and often time-consuming trip south to the nearest roundabout. However, it became a badge of courage for some (Australian males, of course) to defy regulations and to cross Thamrin on foot speed. Particular honours were accorded those who managed to do it without stopping en route.

On a recent visit to Cuba I met some Indonesians, now in their eighties, who had been studying in communist countries in 1965 when Indonesia’s military took over Indonesia. The Suharto government forthwith cancelled the citizenship of such students abroad under the assumption they were all communist. Some of the students gravitated to Cuba where they began new lives. One of them told me that in 2000 President Abdurrahman Wahid restored their citizenship and apologised for their enforced exile. One of the exiled students I met in Cuba said that in 2008 he returned to Jakarta for the first time since 1964. He said the Jakarta he encountered was thoroughly bewildering and he could not deal with the large, noisy and overwhelming metropolis. He said he was happy to return to Havana with its old cars, its quiet streets, its clean air and, in his words, its ‘liveability’. He said that he believed that his life in Havana had allowed him to live in a kind of Jakarta frozen in time.

I defy anyone who has ever lived or even visited Jakarta not to lose themselves in memories as they gaze at this treasure of post cards, photographs, maps and images. Indeed, it is the sort of treatment many other major cities of the world deserve.

Scott Merrillees, BATAVIA in Nineteenth Century Photographs (Archipelago Press, 2000); 282 pp: A$ 85 plus postage from scott@bataviabook.net

Scott Merrillees, Greetings from JAKARTA: Postcards of a Capital 1900-1950 (Equinox Publishing, 2012); 248 pp; A$ 50 plus postage from scott@bataviabook.net; or Rp 495,000 plus postage from www.periplus.com

Scott Merrillees, JAKARTA: Portraits of a Capital 1950-1980 (Equinox Publishing, 2015); 159 pp; A$ 50 plus postage from scott@bataviabook.net; or Rp 495,000 plus postage from www.periplus.com

Ron Witton (rwitton44@gmail.com) gained his BA and MA in Indonesian and Malayan Studies from Sydney University, and then his PhD from Cornell. He has lectured in Sociology and Asian Studies in universities in Australia and Indonesia. He still works as an Indonesian interpreter and an Indonesian and Malaysian translator.

Wat Jakarta nodig heeft, is een eigen Afsluitdijk

Waterbouw

Zonder ingrijpen kan Jakarta in 2025 gezonken zijn. Nederlandse ingenieurs, adviseurs en baggeraars schreven een plan om dat te voorkomen, en hopen nu op miljoenencontracten.

Eva Oude Elferink

9 juni 2017

Jakarta zinkt, en niet zo’n beetje ook. Toch zou vissersvrouw Tati Suryadi (38) haar uitzicht voor geen goud willen ruilen. Vanuit haar spaanplaten huis op palen kijkt ze zo uit op de baai van Jakarta. Denk de hopen aangespoelde plastic even weg, vergeet de olieachtige laag die op het zwartgrijze water drijft. Begin tegen haar dus niet over dat strookje land daar rechts in de verte, waar een houten gebouw met aanlegsteiger nu nog het enige teken van leven vormt. Of erger: de plannen die er liggen om daarachter, precies voor haar uitzicht, een enorme dijk te bouwen.

De metropool met zijn (volgens officiële tellingen) ruim 11 miljoen inwoners zakt jaarlijks gemiddeld zo’n 7,5 centimeter verder weg onder zeeniveau. Op sommige plaatsen in het noorden gaat het een stuk rapper, daar loopt het op tot ruim 20 centimeter. De boosdoener: diepe grondwateronttrekking. De stad wordt in rap tempo volgebouwd met nieuwe winkelcentra en appartementencomplexen en die hebben allemaal water nodig. Wegens de gebrekkige waterleidingvoorziening pompen zij massaal water op, honderden meters diep uit de grond. Het gewicht van al die nieuwe gebouwen drukt de boel verder naar beneden.

Niet de Javazee stijgt, Jakarta zakt weg.

Zeker vier miljoen mensen wonen nu tot vier meter onder zeeniveau. Niet alleen arme vissers, maar ook de rijken die pompeuze villa’s aan zee lieten bouwen. De muren die hen tegen al dat water moeten beschermen, zinken net zo hard mee.

Hoe gevaarlijk dat is, werd duidelijk in 2007. In februari kreeg Jakarta, met dertien zwaar vervuilde rivieren wel gewend aan doorbrekende oevers, een van de meest dodelijke overstromingen in decennia over zich heen. Een paar maanden later, in het droogseizoen, gebeurde er iets vreemds: uit het niets overstroomde de stad vanuit zee. Een half jaar later: nog een keer. „Klimaatverandering, dachten mensen”, zegt Jan Jaap Brinkman (58) van het Nederlands wateronderzoeksbureau Deltares. Tot uit de berekeningen van Brinkman, vanuit Delft opgetrommeld door de Indonesische overheid, een heel andere conclusie kwam. Niet de Javazee stijgt, Jakarta zakt weg.

Er kwam ook een alarmerende voorspelling: wordt er niets gedaan, dan verdwijnt in 2025 het noorden van Jakarta onder water. Brinkman: „Dat is het moment waarop de rivieren zo zijn weggezakt dat ze niet meer in zee kunnen uitkomen.”

Uitgedijde delegatie

Brinkman, die met zijn 1,88 meter boven zijn Indonesische collega’s uittorent, is niet meer weggegaan uit Jakarta. Hij maakt deel uit van een sindsdien flink uitgedijde Nederlandse delegatie aan ingenieurs, adviseurs, en baggeraars. Op verzoek van de Indonesische overheid en gesubsidieerd door Nederland begonnen zij tien jaar geleden met het bedenken van een plan dat Jakarta moet redden. Dat plan ligt er nu en voor Nederland hangt er veel vanaf. Niet alleen vanwege de miljoenencontracten die lonken. Dit is prestige: laat de wereld maar zien dat Nederland nog altijd de onbetwiste koning van de waterkering is.

Maar de vraag is of het project, dat de National Capital Integrated Coastal Development (NCICD) ging heten en tot 40 miljard euro kan kosten, ook echt uitgevoerd zal worden. Met name Brinkmans oplossing voor de kust een dertig kilometer lange ‘Afsluitdijk’ te bouwen, is omstreden. Dan zijn er nog de plannen voor zeventien kunstmatige eilanden, een erfenis van de regering-Soeharto, die op verzoek van president Joko Widodo in de plannen moesten worden geïntegreerd. De lijst met critici en tegenstanders is lang. Onder hen zit Anies Baswedan, de nieuw gekozen gouverneur van Jakarta.

Papieren wekelijkheid

De eerste fase van het project, het verbreden van de verstopte rivieren en versterken van de bestaande zeedijk, is al begonnen. „De no regrets-fase”, zegt Rully, binnen het Nationaal Agentschap voor Ontwikkeling en Planning (Bappenas) verantwoordelijk voor NCICD. Net als veel landgenoten heeft hij maar één naam. Ga maar kijken in de wijk Pluit, waar zandzakken nu voorkomen dat zeewater over de rand klotst. Niet dat het erg helpt. Door scheuren sijpelt water alsnog de nabijgelegen huizen binnen. De gedwongen huisuitzettingen waarmee de eerste fase gepaard ging, leidden al tot kritiek. Maar de echte weerstand komt daarna; bij de Great Sea Wall, een zeewering die van de baai van Jakarta een enorm stuwmeer maakt.

„Het werkelijke probleem wordt daarmee niet opgelost”, zegt Giacomo Galli van de Nederlandse ngo Both Ends. Samen met SOMO (Stichting Onderzoek Multinationale Ondernemingen) en TNI publiceerde Both Ends onlangs een kritisch rapport over NCICD.

Dat hoef je Brinkman niet te vertellen. Hij roept al jaren dat de grondwateronttrekking moet worden gestopt.

„Technisch is het helder wat er moet gebeuren. Er zit alleen geen beweging in. En de tijd dringt. Dit is plan B.”

Foto Cynthia Boll

De huidige watervoorziening van Jakarta bestaat, net als een functionerend rioleringsstelsel, vooral op papier als gevolg van privatisering en slecht afgesloten contracten. Volgens de Wereldgezondheidsorganisatie is tweederde van de inwoners daardoor afhankelijk van water uit de grond. En ook wie dat niet is, gebruikt liever gratis grondwater. Ahok wilde als gouverneur dat heel de metropool in 2018 toegang tot leidingwater zou hebben. Maar door een slepende rechtszaak, aangespannen door burgers tegen de twee private waterbedrijven, lijkt de kans daarop nihil.

OVER DE FOTO’S EN VIDEO

Fotografe Cynthia Boll legt sinds 2015 vast hoe Jakarta en haar inwoners omgaan met wateroverlast. De foto’s zijn gebundeld in het boek ‘Banjir! Banjir!’, waarin acht fotoseries laten zien hoe het water een plek krijgt in de stad en in de levens van mensen. Na Jakarta richt Boll zich nu op andere zinkende steden wereldwijd met haar project ‘Sinking Cities’.

Niet alleen de zeedijk stuit op protest. Dat geldt ook voor de kunstmatige eilanden die voor de kust van Jakarta moeten verrijzen; een verzameling kantoren en luxe appartementen. Het geld dat vastgoedontwikkelaars hiervoor aan Jakarta betalen, is nodig om de rest van plan B te financieren, zegt Rully van Bappenas. In 2013 werd met de bouw van de eerste vier eilanden gestart, waaronder eiland G, of ‘Pluit City’. De deal à zo’n 350 miljoen euro voor het ontwerp en de bouw ging naar de Nederlandse baggeraars Boskalis en Van Oord.

Maar rondom de eilanden is een web van controverse ontstaan door vermeende steekpenningen, gesjoemel met vergunningen en boze vissers die zich niet gehoord voelen. Sinds april vorig jaar ligt de bouw stil.

Lees ook: Verlies Ahok in Jakarta is triomf radicale moslims

Colaflesjes

Op een donderdagmiddag in maart staat Tati met een gebalde vuist in de lucht en een luidspreker voor de administratieve rechtbank in Oost-Jakarta. Met een kleine honderd man, traditionele vissers met spandoeken en bijpassende T-shirts, zijn ze hier om te horen of de rechter hen in het gelijk stelt en de vergunning voor nog drie andere eilanden intrekt. Zo hebben ze meer rechtszaken lopen. Eerder bepaalde de rechter al dat de vergunning voor eiland G ongeldig was. Daartegen ging de lokale overheid in beroep. Hetzelfde gebeurt deze middag.

Met vissen zijn Tati en haar man gestopt, vertelt ze later bij voor huis. Het had geen zin meer. Zie je die pier? Daar zat het altijd vol met mosselen. Nu níets meer. Om vissen te vangen, moest haar man steeds verder varen. Dat kostte uiteindelijk meer brandstof dan hij aan de vis verdiende. Hun ene boot hebben ze verkocht, met de andere, een houten exemplaar waar de verf vanaf bladdert, verzamelt hij nu lege vaten van containerschepen. Aan land brengen die 20.000 rupiah (1,35 euro) op. Het is weinig, zegt ze. „Maar het is tenminste iets.”

In februari is de regentijd het heftigst in Jakarta. Het straatbeeld ziet er dan zo uit:

Je hoeft geen wetenschapper te zijn om te snappen waarom het leven uit de baai van Jakarta is verdwenen. Overal dobbert plastic. Colaflesjes, koekjesverpakkingen. Tel daarbij op de zware metalen die fabrieken stroomopwaarts in de rivieren dumpen. En toen werden ook nog eens die enorme hopen zand in de baai geloosd. Maar de echte nachtmerrie van de vissers, zo’n 24.000 in totaal, is het idee van die dijk. Milieu-activisten en wetenschappers waarschuwen dat, tenzij de rivieren grondig worden schoongemaakt, de baai dan verandert in een stinkend giftig meer.

„Het zal geen blue lagoon worden, nee”, zegt Victor Coenen met een Hollands gevoel voor understatement. Namens ingenieursbureau Witteveen+Bos leidt hij het Nederlandse consortium. En nee, ook het zinken van Jakarta stopt er niet door. „Maar het alternatief is over een paar jaar een deel van de stad evacueren.” Bovendien, zegt Coenen: „Het is niet dat we graag een dijk willen bouwen, en dus maar een probleem verzinnen. Jakarta heeft een enorm probleem. Als daar niet snel iets aan wordt gedaan, is een grote constructie de enige oplossing.”

Het is niet dat we graag een dijk willen bouwen, en dus maar een probleem verzinnen. Jakarta heeft een enorm probleem.

STANDAARDEN NIET GEVOLGD

De Nederlandse overheid stak tot nu toe 11,4 miljoen euro uit het budget voor ontwikkelingshulp in de ontwerpfase van NCICD. In hun rapport schrijven Both Ends, SOMO en TNI dat de overheid daarmee de eigen standaarden voor ontwikkelingshulp niet volgt, omdat het project mogelijk tot grote milieuschade leidt en de lokale bevolking vooraf onvoldoende is geïnformeerd en inspraak heeft gekregen. NCICD kreeg ook 500.000 euro vanuit het ‘Partners voor Water’-subsidieprogramma.

In het rapport Social Justice at Bay waarschuwen Both Ends, SOMO en TNI voor het ‘giftige meer’ dat voor de kust van Jakarta ontstaat als het NCICD-project doorgaat. Ook bekritiseren zij het gebrek aan inspraak voor de ruim 24.000 vissers die hun bron van inkomsten verliezen. Maar bovenal, schrijven de opstellers, voorkomen de plannen niet dat Jakarta verder zinkt. Wil de lokale overheid die problemen aanpakken, dan lopen de geraamde kosten (nu maximaal 40 miljard euro) veel hoger op.

Leugen

Maar als de afgelopen tien jaar iets hebben laten zien, dan is het dat besluiten eindeloos vooruit geschoven kunnen worden of door nieuwe wetgeving plots achterhaald blijken. En dan kan het ook gebeuren dat iemand anders, met een andere mening, het politiek voor het zeggen krijgt. Zo was de ontwikkeling van Jakarta’s baai een van de belangrijkste thema’s tijdens de recente gouverneursverkiezingen. De zittende gouverneur Ahok verleende vergunningen voor enkele kunstmatige eilanden, zijn rivaal Anies beloofde de bouw ervan definitief stop te zetten. Anies won de verkiezingen.

In een zaal achter het Onafhankelijkheidsmuseum in Jakarta zijn de aanwezigen daar maar wat blij mee. Dezelfde gezichten als een maand eerder bij de rechtbank, dit keer zonder spandoeken. Niet nodig, de presentatie van het SOMO/Both Ends-rapport is een bijeenkomst van gelijken. Ook gouverneur Anies zou komen, maar zag daar op het laatste moment van af. Gaat hij straks echt een streep door het project trekken? Ze hopen het hier vurig. „NCICD is een grote leugen”, klinkt het. En er is maar één groep die ervan profiteert. „De Hollanders, natuurlijk.”

Meneer Sumari ruimt op, na een overstroming in de wijk Muara Baru.

Foto Cynthia Boll

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten