Homer Sykes This is England Poursuite Editions

Published 2014 for my exhibition at the Maison de la Photographic Robert Doisneau. Paris.

9 x 6.25 inches 36 pages.

Homer Sykes: 'Photographers are lemmings'

Fed up with photojournalism, Homer Sykes decided to chase after Britain’s inner essence in the 1970s. From awkward stripteases to weary miners and picnics at the races, he caught a country seething with class conflict

Miners resting, Snowdown colliery, Aylesham

Snowdown colliery, Aylesham, Kent, 1970s. All photographs: Homer Sykes

Sarah Moroz

Wednesday 9 September 2015 13.37 BST Last modified on Wednesday 9 September 2015 17.04 BST

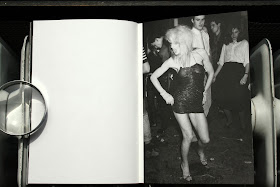

It’s 1971, and two bashful-looking women are doing a striptease on stage at a village fair. A giant sliver of Humphrey Bogart’s eye is visible too. Bogie’s expression from Casablanca, so key to his legacy, seems prescient here: “Here’s looking at you, kid.” In just one photograph, Homer Sykes has made a perfect voyeuristic echo of a gawking audience, a true glimpse of the male gaze.

You can read a lot into every photograph taken by Sykes. His show My Britain 1970-1980, now on in Paris, traces daily life in the UK – and overflows with social commentary on the crossroads of the class system.

Striptease tent at Pinner annual fair, 1971

The picture Coal Miners, Snowdown Colliery, Kent (1976) is a case in point. He went to shoot miners voting about the unions, but what could have been a pedestrian look at policy turned into a filmic glance at men smoking, naked and weary, in their locker room. It summed up the plight of the trade forcefully. “I always try to go through the door that’s closed, to see what’s really going on,” Sykes says.

He started out as a photojournalist in the 1970s, working for the Observer, the Telegraph, Newsweek and Time. But photojournalism was often an awkward fit for him. “If you get a pack of guys going off to shoot something … they all do the same picture. Photographers are lemmings,” he says. “I didn’t want to be just a magazine photographer who delivered pictures to fit a brief.”

Instead, he became a portraitist of his own country, probing the customs deemed typically British. In the early 1970s, he went to Lancashire to shoot the local Easter celebrations, which inspired a long-term project. In 1977, he published his first book, called Once a Year: Some Traditional British Customs, on old-fashioned fetes from Garland Day to Burning the Bartle. Forty years on, he’s gone back to re-photograph the rituals, and the differences are palpable. “Everyone’s aware of being photographed now,” he says. Moreover, he explains, in the 1970s “it was relatively easy to distinguish an upper-class couple by the swagger of their dress.” But today’s “urban classless metrosexual man is impossible to pigeonhole”.

A picnic at the Derby, Epsom Downs, Surrey, 1970

Sykes likes to home in on details that hit a nerve. “I’m always trying to find something that sums up what’s going on, what I’m feeling, what British society is feeling,” he says. “I’m always looking for contrasts.” The working class and the well-to-do are often juxtaposed in comic images that show their incongruities. One such example – A Day at the Races, Derby Day Picnic Horse-Racing at Epsom Downs (1970) – pits the haves and have-nots in the same shot. In the car park at Epsom, a cheery picnic is propped up before a flashy car, whose prim owners have returned with their chauffeur to claim it.

Margaret and Barry Kirkbride, Workington, Cumbria, 1975

In this exhibition, Sykes makes a mirror using two couples of different social strata. Margaret and Barry Kirkbride. Workington, Cumbria (1975) are photographed in the north of England: long hair, tartan trousers, hip and young and working class. “They looked so typical,” Sykes says admiringly. Nearby hangs another young couple: he’s in a Prince of Wales checked suit and loafers, bottle of Pimms in hand; she’s in a Laura Ashleyesque floral dress and espadrilles. “How English can you get!” he says.

His shots may seem like lucky happenstance, but they’re extremely precise. “I don’t ‘snatch’ pictures,” he says. “Everything is planned – it takes very little time to do it, but it’s all thought about.” He looks for cues from 20ft away; when a person looks promising, he approaches, assessing the appropriate background, until he’s about eight feet away. Back when he was using a Leica camera, he would measure the exposure and pre-focus beforehand. “I normally bend my knees a little bit,” he says, showing me with a little plié, “and go tch-tch-tch – three or four frames. I shoot quietly. No eye contact.” He knows the right background by instinct. One day, he trailed a woman wearing a floral hat around the Chelsea Flower Show in London for some minutes. When she stood right before a wall of flowers, the flora on her head blended in perfectly. He knew it was the perfect shot.

Waiting for money to be washed up in the tide after a storm, Brighton beach, 1970

Sykes is antsy for greater recognition of his life’s work. He photographs less regularly these days, but he’s still highly ambitious. “When I was younger, I thought I could be a Magnum photographer, and looked up to Cartier-Bresson, Winogrand, Friedlander,” he says. “I arrogantly set about to do that. And I’m still trying.”

My Britain 1970-80 is at Les Douches Gallery, Paris, until 31 October.

Homer Sykes

Nearly four decades after seeing photographic prints hanging on the walls of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, British documentary photographer Homer Sykes welcomes the acceptance of photography by Britain’s art establishment, writes Graham Harrison.

The 2007 Tate Britain show ‘How We Are : Photographing Britain’ was the first major exhibition of photography at the premier gallery for British art.

An examination of the British identity through the eyes of the nation’s documentary photographers ‘How We Are’ featured the work of Martin Parr and Daniel Meadows. It also featured the work of Homer Sykes who was inspired to begin a life as a documentary photography during a visit to another great gallery, nearly 40 years earlier.

FINDING A STYLE

Since that moment of inspiration Sykes’ career has followed a long path that began with self-financed long term documentary projects and also included editorial and commercial commissions, agency work and teaching before returning to the commitment of more personally inspired documentary projects.

The two most recent of these Hunting with Hounds and On the Road Again have been published by Mansion Editions, his self publishing concern created in 2002.

Homer Sykes was born in 1949 in Vancouver, Canada to American and Canadian parents. His father, killed in China before Homer was born, was a keen amateur photographer as too, it transpired, was Homer’s new step father.

He moved to England with his mother when she remarried in 1954 and by the age of 16 Sykes had built his own darkroom under the the eves of the art department at his boarding school. He also had a darkroom at home for use during the holidays (if the chemistry will not be missed the wonder of your own images emerging in the gloomy red glow of a safe-light had an intimate alchemy now lost to the electronic chip and computer screen).

The young Homer became an avid reader of Camera Owner (later Creative Camera) and the new newspaper colour supplements. He became interested in creative magazine photography, and in images with a personality that could be attributed to a particular creator rather than to just any photographer. He became especially interested in photographs that were good enough to explain themselves and needed no text.

In 1968 Sykes enrolled for a three year photography course at the London College of Printing (LCP – now LCC) and on his first summer vacation travelled to America where in New York he visited the Museum of Modern Art. There, hanging on the same walls as canvases by the greats of modern painting he found prints from the acknowledged masters of documentary photography. Sykes realised that photography was already seen as art in the United States.

Burk Uzzle, Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, Robert Frank, Bruce Davidson and Henri Cartier-Bresson all became instant heroes. “I hoped to – and thought I could – do what they were doing and set out to do it” says Sykes. He wanted to create a fusion in his own style between the American street photographer genre that he loved (because of the way their images appear spontaneous, accidental and stylish) and that of the humanitarian reportage and documentary photography of the old and great Magnum photographers.

Once a Year – Some Traditional British Customs : a discovery in the LCP library led Homer Sykes to his first major, and most career defining subject.

A SUBJECT OF ONE’S OWN

Back at the London College of Printing, Sykes spent his lunch hours wandering the nearby tenements working on his street photography, and browsing magazines in the college library.

Looking for something to shoot for an Easter holiday project he came across a copy of In Britain magazine and a picture of the Bacup Coconut Dancers and decided to travel to Lancashire to photograph their annual Easter dance.

“I then realised that there were many other customs that no one was documenting, and it became fascinating researching the project, which began to grow and grow” said Sykes who spent days at the English Folk Dance Society and other libraries hunting down obscure traditional customs that took place annually around Britain, and then turning up with his Leica M2 and M3 in distant towns and villages to find himself the only photographer in attendance.

Homer Sykes had stumbled upon his first important, and most career defining subject. Success followed with the touring exhibition ‘Personal Views 1850-1970’ put on by the British Council in 1970. In 1971 ‘Traditional British Calendar Customs’ was shown at the Arnolfini Gallery, Bristol, and ‘Traditional Country Customs’ where Homer’s work was shown with the photographs of Sir Benjamin Stone, was held at the ICA in London. Homer’s first book Once a Year – Some Traditional British Customs was published by Gordon Fraser in 1977.

‘How We Are’ : four of the most iconic images of British customs taken by Homer Sykes in 1970 were hung on the walls of Tate Britain in 2007.

BUILDING A CAREER

One of Homer’s teachers at the LCP was David Hurn, the Magnum photographer who had been with the legendary agency since 1965. Hurn’s flat was just down the road from where Homer lived, and the aspiring photographer used to hang out in the famous meeting place to soak up the atmosphere. There he met Josef Koudelka and Ian Berry, both of whom he got to know well. He also became friendly with Peter Turner of Creative Camera, and Bill Jay who was then publishing Album magazine.

Crucial to his future survival Sykes learnt how vital retaining the rights to his work would be “I once went round to Ian Berry’s home to do some copying of colour slides into B/W and he showed me his monthly archive sales statement from Magnum. We talked about copyright and how important it was for a freelance to keep ownership. At a similar time I remember a conversation with David Hurn in his flat about the importance of the Magnum archive, and how keeping the rights was essential for an independent photographer.”

Around that time in the early 70s Sykes started working with and supplying the agency Viva in Paris, the John Hillelson Agency and Camera Press in London, and Woodfin Camp in New York.

“I was shooting weekend demos, and small news features for them, as well as doing general commissions for these agents. So I knew about selling on a story and stock sales, and retaining my copyright when commissioned.”

“Those days were very different from now, I remember when Viva sold to Bunte the German magazine, a set of photographs of mine taken in Barbados in 1973. My share was £200 and this was not for their use – Bunte had bought the first rights, just to look at the pictures !”

As they offered travel and the possibility of regular and interesting well paid work Sykes sought and got work from all three of the UK’s weekend colour supplements The Sunday Times, The Telegraph and The Observer.

Sykes also worked on hard news stories abroad for the weekly news magazines Newsweek, Time, and the short lived Now! magazine. Assignments included covering conflicts in the Middle East, West Africa and Northern Ireland. For some time it seems Homer was a long way from the coconut dancers of Lancashire.

The compromise was the discrete and lightweight old Leicas had to go into a cupboard and he started using Nikon SLRs which with built-in metering, motor drives, and a variety of optics were more suited to shooting the transparency films required by the magazines of the time.

Today Sykes welcomes the new freedoms automated digital cameras have given to the professional photographer. With his Leicas Homer says he always worked in black and white, intuitively “shooting for the shapes” and enjoying the spontaneity the cameras afforded. Moving by necessity to SLRs and slide film slowed the process of working.

But now he believes the full automation of digital equipment has given him back that old Leica spontaneity. This time in colour. “We are just at the beginning of the digital age, and we should explore the freedoms the technology affords us” says Homer. “The nature of digital means the profession is far more competitive than it ever was, however what’s still most important is what you see, why you look, and how you interpret what you are looking at.”

Homer adds, “It doesn’t really matter about 10 or 20 million pixels, ultimately the best photography is about vision.”

HOLDING FIRM

In the 1970s and 80s Homer had many arguments with picture editors and lost commissions because of his insistence on implementing what he had learnt from Berry and Hurn although many picture editors of that generation sympathised with his argument. Some even turned a blind eye to ensure he kept his work.

In 1989 Sykes joined Network Photographers (which had been founded by Mike Abrahams, Mike Goldwater, Barry Lewis, John Sturrock and Chris Davies) but the hoped for stock sales and assignments did not materialise, and by 2000 Network found itself in serious trouble.

Homer believes that neither the agent nor the photographers had grasped the reality of the new photographic age. The old photo agency business dependent on established relationships and courier delivered transparencies and prints was disappearing fast. New well financed global digital corporations like Corbis and Getty were changing the supply and demand of images and editorial stock prices were starting to drop. On top of this new vibrant agencies like Laif and young hungry photographers were moving into Network’s market position.

“We thought Network Photographers could be a boutique agency in a global business and that the Network Photographers name would carry us through the difficult times” says Sykes, “looking back that was quite ridiculous, not least because we were under-funded and badly advised.”

In 2004 fresh finance was found and a new management team was put in place, but it transpired that the new management had no practical experience of the photographic business and Sykes was, “kicked out” of Network because he would not sign an exclusivity contract. Although invited to rejoin in 2005 Homer found that the die had been cast and Network folded in February 2006.

“I never wanted to run my own picture library, but at the same time I was aware of the importance of my collection of images, and of their long term value” says Homer who concedes that life has come full circle, as he now spends most of his time developing and running his archive, much as he had done in the 1970s.

“However, I really wish I was able to do more photography and spend less time in front of a computer screen. But the hope is that once my entire archive is online – and providing the new online libraries don’t change their procedures too much over the coming years – I ought to be able to do less and less online work and get back to photography, creating new stories, sets of images and shooting more personal work.”

The important thing Sykes says is that there is now a massive world market, thanks to the web, “especially for single iconic stand-alone images.”

The Life Library of Photography book Documentary Photography (1970) defines documentary photography under the title, “To See, to Record – to Comment,” as being a visual representation of a deeply felt moment, as rich in psychological and emotional meaning as a personal experience vividly recalled.

For Homer Sykes documentary photography is about working on a subject over a long period of time, getting to know and understand it. “I have always tried to add my personality to the images, to their content and the way in which they are taken, and certainly I want to be involved in how they are edited and put together” says Homer, adding, “all this takes time and commitment.”

“Revisiting my early work has actually allowed me to move forward,” Homer Sykes about On the Road Again, which he self-published in 2003.

To see what Homer means take a look at his most personal of projects, the self-published book On the Road Again. Here photographs taken on his Leica M3 and standard lens during his early travels in the United States in 1969 and 1971 are brought together with images taken in 1999 and 2001 using the same camera and lens which had come back out of the cupboard and been dusted off.

On the Road Again received good reviews, and raised Homer’s profile giving him back the confidence that had been sapped by the Network debacle.

“And of-course it created income. I wanted to start working on my own stories and shoot pictures for myself over long periods of time, as I had originally planned to do. I realised that I had to move on from the day to day, week by week photography that I had been doing to make a living to a more independent, creative position.”

“I also realised that there was an art photography world that I wanted to join. I hoped that my most recent books Hunting with Hounds and On the Road Again might help me into that area, and I think they have.”

“It is interesting that going back and revisiting my early work has actually allowed me to move forward.”

Speaking about his work from the 1970s being hung on the walls of the premier gallery of British art, Homer Sykes says, “the great thing is that photographers have finally been accepted by the art establishment, and this could just be the beginning of a renaissance in documentary photography values in Britain.”

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten